In fighting the franchise tag, Bell chose to save his soul.

Teammates publicly called him selfish, dogged him for ruining their season, complained about his salary, and rummaged through his stuff like pirates when he decided to stay away. They just didn’t understand what Le’Veon Bell knew: professional football wants to own the players, body, and soul.

Most of Bell’s Steelers teammates had already been bought. But not Bell. He has other plans. He sees football for the business that it is. He sees football as a power struggle between owners and players on and off the field. He sees football as a means to freedom and not an end.

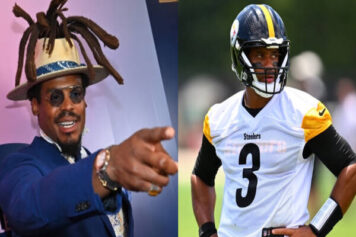

In short, he understands his worth. And by staying away from football for a season, and yes, giving up nearly 14.5 million dollars, he’s willing to bet on himself rather than give his body to the league. In fighting the franchise tag, Bell chose to save his soul.

The franchise tag is a tool the owners use to restrict free agency and a ploy to limit the power of labor. And with players never in lockstep during CBA negotiations, the tag will never go away.

Because of the monopolistic structure and cutthroat nature of a business where bodies are seen as disposable, football players have always tried to fight to get an extra economic advantage against the owners. And they always faced criticism from teammates who saw their actions as selfish, owners who felt they were being unreasonable, and fans who thought they were being greedy.

Bell’s situation is no different. But to truly understand his battle, we have to see his fight for free agency as a battle from Black labor against power. And, in sports, it seems like the biggest labor battles are always fought and led by Black players.

It is Curt Flood in baseball and Oscar Robertson in basketball. With the backing of his Black agent, Adisa Bakari, who gives all of his clients a copy of Bill Rhoden’s hard-hitting, Forty Million Dollar Slaves, Bell and Bakari have turned this into a Black labor struggle. By withholding his labor for a year to protect his body as he battles against the brutal franchise tag, Bell is showing a new way to do business in the cutthroat NFL.

Bell’s business decision stands in a long line of Black football players who have tried to pave the way for economic power. There’s always a history.

In 1957, Jim Brown was the first player to hire an agent, and ten years later, in the ultimate power move, five Black players from the Cleveland Browns; John Wooten, Leroy Kelly, Mike Howell, Sidney Williams, and John Brown, held out together to renegotiate their contracts.

In a Black power block, to take some power back, the five Black players, all members of Jim Brown’s Negro Industrial Economic Union (NIEU), had individual contract demands, but demanded that the Browns negotiate all their deals together, and they ordered that if the Browns wanted to cut and trade one player, they had to cut or trade them all.

Williams wanted a guarantee of equal playing time in the pre-season, Wooten, an all-pro player who felt he out-performed his contract, wanted a new deal and more money, Brown wanted to negotiate a new contract before he hit free agency the following year, and Howell and Kelly, who had earned starting spots wanted to be paid as starters.

In Kelly’s case, he had replaced the great Jim Brown, finished second in the league in rushing the previous season behind Gale Sayers, and had a contract that came up at the end of the year. Like Bell today, he was a rising star in the league and knew he was due for a huge contract, and thus he did not want to risk injury before he got his big payday in free agency. To force the Browns’ hands, the five Black men stood together and boycotted training camp.

They had another Black power move to fight the system. For their spokesperson and lead counsel, they hired Carl Stokes, who was also running for mayor of Cleveland, and who would ultimately become the first Black mayor in a major city.

They argued that since the NFL and AFL had merged that year, that constituted a monopoly and thus destroyed their ability to negotiate a fair contract. Before the merger of the AFL and the NFL, Black players had their first real shot of making a decent wage playing football, and with another league to negotiate against, they saw their salaries rise.

No longer could owners give football players a “take it or leave it” offer. But the merger killed that. And through Stokes, the players articulated an argument that was grounded in the reality that they were Black men fighting for labor.

Two years before Curt Flood famously said he was a well-paid slave, Stokes told the local press that “you pay a man $50,000 and he can still be reduced to peonage,” and noted, “since we abolished slavery, men have held the right to play for the amount they’re worth, according to the position and role they hold.”

This time, unfortunately, the power won. The Browns played hardball and refused to negotiate. They also fined the men for every practice they missed, 16 days in total. Before players were making millions of dollars, very few could withstand major fines like Le’Veon Bell.

Wooten tried his best by paying the others fines, but in the end, it was too much. Howell signed his contract before he hit free agency, more than likely for less money than he would have if he risked injury and waited for free agency. The Browns traded Brown and Williams and refused to negotiate with Wooten and Kelly. The team traded Wooten a year later after he complained about racism on the team. Kelly, without a new contract, had to risk his body for the money.

Although timid at the beginning of the season, because he worried about an injury that would reduce his chances of making a lot of money, Kelly won the rushing title. As a free agent, he made the Browns pay. The future Hall of Famer signed a 4 year $300,000 deal, a huge leap from his $20,000 salary.

Whether people saw the Black five players’ actions in terms of winning or losing, their enlightened fight was part of a struggle football players have had to battle with owners to get their rightful share. And it always seems like it is the Black athlete willing to combat. And now, Le’Veon Bell is in that same fight.

Like the Browns Five, we have to see Bell’s battle in terms of race and labor.

When Carl Stokes said that these well-paid athletes could still be reduced to “peonage” and that “since we abolished slavery, men have held the right to play for the amount they’re worth, according to the position and role they hold,” we can see the similarities with Bell’s agent, Adisa Bakari.

In a recent interview with Jesse Washington, Bakari said, “Now, my analysis of things certainly is shaped by the unique history of African-Americans. My analysis of the economics of the NFL certainly are shaped by the historical experience of black athletes and the mistreatment of black athletes. So is that history interwoven in my thought process? Of course.”

If Bell’s power move works, he will be rewarded. But more important than his financial success, he is also fighting for his fellow football players’ future. And that is what the Black labor struggle has always been about; risking one’s livelihood to fight for others.