Black female athletes, in particular, continue to be haunted by controlling images – the racist, sexist images of black women’s bodies that emerged in essence during the early stages of western colonialism.

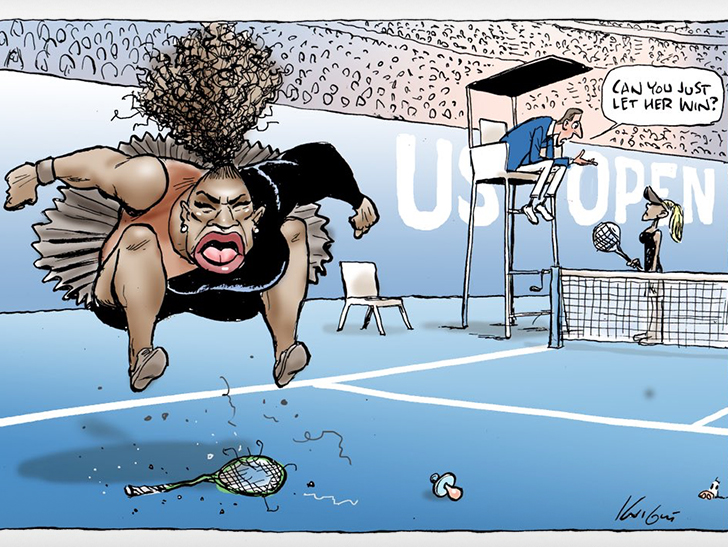

This morning, post the Black Girls Rock! Award Show which aired last night, and the amazing display of Black Girl Magic performed by Serena Williams and Naomi Osaka on Saturday during the 2018 tennis U.S. Open, people in general and black women and girls, in particular, were confronted with a blatantly racist/sexist cartoon.

Williams body appears out of control and reproduces images of black women as aggressive and beast-like while the image of her opponent completely erases Osaka as a woman of color by replacing her with a blonde, white, female figure.

Such an image speaks simultaneously to the hyper-visibility of black athletes as well as the erasure of black female athletes in its portrayal of misogynoir.

That in 2018 we have commentary of a republican candidate for governor in Florida inventing the phrase dont monkey this up, in reference to his Black democratic opponent; and a U.S. open tennis umpire stealing first a point, then an entire match, culminating in a $17,000 fine for Williams only further illuminates the mythos around post-raciality and the continued dominance of sexism in sport.

Black women are often depicted as being overly aggressive, and this mornings cartoon, as well as tennis umpire Carlos Ramos response to Serena during the U.S. Open only further highlight this controlling image of black femininity, one that is often hoisted upon the GOAT.

Serena is often portrayed as being too much for the white world of tennis: from her clothing choices (see: The cat-suits circa 2002 and 2018), to her hairstyles (braids, color, beads and more), to her impassioned responses to thievery and blatant disrespect such as was foisted upon her during Saturdays match.

Serena challenges the dominant discourse about what tennis is, and has since the beginning of her career. She has pushed its boundaries and carved out a space for herself and other women of color – black women in their various forms in particular. She is a champion because her game is unparalleled, and she refuses to let racism and sexism stand in the way of her greatness.

2018 US Open Highlights: Serena Williams’ dispute overshadows Naomi Osaka’s final win | ESPN

Naomi Osaka becomes the first Japanese player to win a Grand Slam after she defeated Serena Williams 6-2, 6-4 in the final of the 2018 US Open but the match will be remembered for the emotional exchanges between Williams and umpire Carlos Ramos, who handed her three violations, including a game penalty.

Her challenge of the umpire during Saturdays match was, as she said, more for others than for herself because she did not benefit from calling out the injustice that she was presented with, but rather was penalized instead. Nevertheless, by making her challenge known and demanding an apology, she opens the conversation for much needed changes to the system.

We are reminded by her presence that no BODY in the tennis world has been as scrutinized (read: the most (drug) tested athlete in the game) or as penalized (read: the loss of a point, and then a match), as Serena, and we cannot ignore the fact that the response to her body is based both on her race as well as her gender; hence misogynoir at its peak.

Nevertheless, by standing as a challenge to the system, Williams labor (in its multiple forms) presents an opportunity for re-imagining a game that has shifted since the moment she set foot on a tennis court, and will continue to shift as she and other women (women of color in particular) vocalize their displeasure with the markers of racism and sexism that have persisted for generations.

Serena Williams is the GOAT, and the tennis court is her domain. One that can and will be transformed if it wants to maintain its relevance in an ever changing world.

***

Letisha Engracia Cardoso Brown PhD., is a Presidential Pathways Postdoctoral Teaching Fellow at Virginia Tech University. Her research focuses on representations of black female athletes as well as race, social relationships, and food practices. You can find her work in the South African Review of Sociology, and the Palgrave Handbook on Feminisms and Sport, Leisure, and Physical Education.