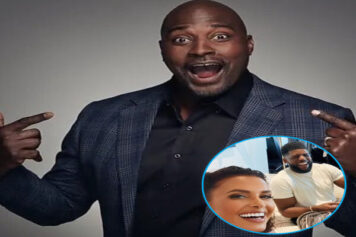

Meet Kenneth Shropshire, a man who many call the smartest man in all of sports.

With the NFL Draft approaching on April 26th, and the NBA Draft soon to follow on June 21st, a select few elite college athletes will have their professional sports dreams come true. Most of them will be African-American, and some of them will become household names.

In our series, “The Black Sports Agent“, we wanted to highlight some of the folks that are doing big things on the business side of the games that we love.

***

For those who study the business side of athletics, they’ll tell you that Kenneth Shropshire – the current Adidas Distinguished Professor of Global Sport and CEO of Global Sport Institute at Arizona State University who recently closed out a 30-year career as an endowed full professor at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, where he was also director of the Wharton Sports Business Initiative, professor of Africana Studies, and academic director of Whartons sports-focused executive education programs – just might be the smartest man in all of sports.

He began his professional career working in law and representing pro athletes after graduating from Columbia University’s Law School in 1980. His many job descriptions include author, attorney, corporate executive, arbitrator, educator, public speaker and consultant, among others.

He’s also a television and media personality who has provided commentary for the likes of Nightline, CNN, the New York Times, USA Today, The Wall Street Journal, NPR, The Atlantic and Sports Illustrated, among a host of others.

But perhaps a more concise and appropriate job title might simply be “Visionary Disruptor.”

The most recent of his 12 books, “The Miseducation of the Student Athlete: How to Fix College Sports“, which was co-authored by Collin D. Williams, Jr, lays out a manifesto and call to action to increase the likelihood that student-athletes succeed both on and off the field with what they call a “Meaningful Degree Model.”

Some of his previous books include “Sport Matters: Leadership, Power, and the Quest for Respect in Sports,” “Negotiate Like the Pros: A Top Sports Negotiators Lessons for Making Deals, Building Relationships and Getting What You Want,” and “Being Sugar Ray: The Life of Americas Greatest Boxer and First Celebrity Athlete.”

Additional works include the foundational books “In Black and White: Race and Sports in America,” “The Business of Sports,” and “The Business of Sports Agents.”

Any meaningful discussion about sports business, agents and the true power of athletics is incomplete without including Shropshire in the mix.

And after over 40 years of building one of the most impeccable resumes around, the man will tell you that he didn’t start out with the grand vision of being at the forefront of utilizing sport and its social impact to transform the world.

Coming out of high school in the Crenshaw District of Los Angeles back in the day, he simply wanted to play pro football.

***

The Shadow League: When did you have this vision of working on the business side of sports, not only as a career choice, but to also enact some societal shifts through the games that we love?

Kenneth Shropshire: Like so many other stories, I thought I was going to be a pro football player. I can’t think of a time in life from when I was a kid until I was a sophomore at Stanford where I didn’t think it wasn’t going to happen, when it wasn’t the primary part of what I was going to be.

TSL: What changed, in terms of your vision, when you were playing college football?

KS: I played football at Stanford for four years. Well, I practiced hard for four years but didn’t see much playing time on the field. After a couple of years, I said, “OK, this being an NFL player thing isn’t going to happen for me.”

I didn’t have the mental fortitude to keep pushing the way you know guys have to do to be successful at the highest level of sports. Also, I began to understand that there were a lot more opportunities to work in pro sports other than simply being a player, and that was simply being a byproduct of having ended up at Stanford.

TSL: What was your thought process in going to Stanford as opposed to someplace else? I’m sure you had plenty of other options, both as a student and an athlete.

KS: They’d gone to the Rose Bowl in 1971 and 1972 when I was in high school, so Stanford was more of a football move for me more than anything, not, “Oh, this is this great academic place.” But I was fortunate enough to be there because it was at a time that you started to see agents representing athletes.

I’d almost gone to Columbia as an undergraduate. Other than the Naval Academy, they were one of the first schools that recruited me to play football. I actually took a trip to New York. I’d never been there before, but I decided that it was too far.

TSL: So realizing that a pro football career wasn’t in the cards and seeing some of your teammates and other athletes being represented by agents when they turned pro changed your thought process?

KS: Between that and some other circumstances, I thought, “Why don’t I go to law school?” Because I could still be involved in sports, the thing that I loved, in that type of way.

TSL: You eventually graduated from Columbia Law School in 1980. What was your thought process in terms of making some of your first professional moves in the legal field?

KS: That was when I started to understand what you could do with sports. I got a job with a law firm in Los Angeles that did a lot of sports work. They represented Jack Kent Cooke’s interests when he owned the Lakers and represented about 50 baseball players. I later got a job with the L.A. Olympic Organizing Committee which was my first full immersion into it and away from the law side.

TSL: What were some of the challenges you faced at the time as a young man fresh out of law school trying to make your mark in the sports business?

KS: It took me a year and a half to pass the California Bar Exam. That was a lesson in going from failure to opportunity. During that process, I said, “I gotta do something, this is not gonna work.” And when things aren’t going well, you start thinking, “Well, maybe I just don’t like this stuff.”

But as I passed the bar and got the job with the Olympics, I said, “You need to try this lawyer thing full speed ahead for a minute.” And over a two-year period, I was strictly practicing law and representing some boxers and track and field athletes, among other things. I really had a chance to regroup and think, “What do you really want to do?”

TSL: Let’s rewind for a minute and take me back to the Shropshire household when you were growing up in Crenshaw.

KS: I was blessed and grew up in a middle class family. Both of my parents went to Historically Black Colleges and Universities and my father had been in the military. They were determined, despite having some financial success and stability, that we were going to stay in the community. So we grew up in Crenshaw and I didn’t have a lot of exposure to the white world until I hit Stanford.

TSL: Being a young guy on the move and involved in the 1984 Olympics in your hometown had to be exciting. What were you doing?

KS: I ran the boxing competition and that’s where I began to see a lot of issues.

TSL: Was that when things came into focus in terms of the social constructs and challenges that were inherent, from an equity standpoint, on the sports landscape?

KS: That was the big breakthrough moment that propelled me towards what I’m doing now around the social consciousness issues and the opportunities that we don’t necessarily get.

TSL: What happened after the ’84 Olympics?

KS: I’d gotten the job as a professor at Wharton and received a call from an old Stanford professor of mine, Bill Gould. He’d been asked by Willie Stargell and Frank Robinson, right after Al Campanis said on Nightline on the 40th anniversary of Jackie Robinson integrating Major League Baseball, that Blacks lacked the necessities to be big league managers.

They called professor Gould, who was a lawyer and asked, “Can you help us organize?” At that time, Gould was an arbitrator with Major League Baseball, so he called me and said, “I can’t do this, but maybe you can.”

TSL: What shakes loose from there?

KS: So I went to the winter meetings and I’m in this room with all of my baseball heroes – Willie Stargell, Frank Robinson, Dave Winfield, you name them and they were there. They did this ceremonial thing where they said, “OK, we all know what the issue is, come to the mic and tell us what you want.

And man after man, especially the guys who’d retired, said, “I just want to coach. I just want to manage.” And they weren’t able to get jobs.

It was there where I started to think about not just the playing opportunities but the business side and what I could do to help these opportunities come about. I was involved in meetings with the commissioner of baseball and that inspired me to write the first book I did with a race focus, “In Black and White: Race and Sports in America.”

It was the third book I had written, but like any scholar, it took me some time to shift into something that I was really into. And over the years, I’ve been blessed to consult with the NFL, the NCAA, Major League Baseball and a number of entities on race issues, trying to move the needle.

TSL: You were a living, breathing institution at the University of Pennsylvania. When I got there in the fall of 1988, I can’t tell you how many of my older peer mentors and upperclassmen implored us younger students to take your Legal Studies class at Wharton. As a professor and role model, you were one of our cherished resources.

A lot of people were shocked when, after 30 years on campus, you moved on to take the job as the CEO of Arizona State’s Global Sport Institute. How did that come about?

KS: Being at Wharton and Penn was great. I could have sat there forever. There are some great professors and fantastic students. And like anywhere, there are some professors that have stayed too long, that are burned out and not doing what they used to do or what they could do.

There was a lot of stuff that I still wanted to do, especially sports and race-related, and I also had some interest in media, documentaries, podcasts and storytelling.

I got a call from Ray Anderson, who had been working at the NFL. He was a teammate of mine at Stanford and had been my host on my recruiting visit there. Ray called me about three years ago and said, “I have an offer to be the Athletic Director at Arizona State and I want you to negotiate my contract.”

TSL: What happened from there?

KS: In the process of negotiating Ray’s deal, I wound up meeting with Arizona State’s president, Michael Crow. Early on in the negotiation, he says to me, way out of the blue, “What would it take to get you here?”

I said, “Man, you gotta be kidding.”

First of all, we’re in the midst of a negotiation and second of all it wasn’t something that I was thinking about. So we got the deal done and two weeks later, Ray called and said, “You know, that guy was serious. You should have a conversation with him.”

I said, “Man, if anything, I’m thinking about being done!”

TSL: So how did those conversations progress with Arizona State’s president?

KS: It was a two-year long conversation, where he literally gave me a whiteboard and said, “Think about what doesn’t exist in the world in terms of an academic institution focusing on sport.”

I told him, “If you can give me the power of the whole university, not just the law school or the athletic department, if I can have people talk about whether Gatorade works, or concussions, that can talk about the Rooney Rule, athletic performance and so many other issues, let me be the guy that runs it. And give me the power of the journalism school and tell me that I can have a portal to find the best way to push out this information in a really straightforward way that people can use, with some deep research underneath it if people want to get to it, because obviously it’s an academic institution.”

We kept going back and forth and at one point, he said, “I’d like to do this. Would you like to come run this?”

I said, “Nah, I’ll be a consultant and help you do this. I’m fine.”

TSL: So what eventually changed your mind?

KS: Ray had been the Athletic Director for about a year at that point and said, “Can you come with me for a meeting with adidas? We’re trying to re-work our deal and they might be interested in hearing about this Global Sport Institute that you’ve been contemplating.”

I went in there, gave the talk to Mark King, the President of adidas North America and pretty quickly afterwards he said, “I want to be a part of this.”

The novel thing, as you look at apparel companies, this was, as far as we could tell, the first time they said, “We want to invest on the academic side.” Obviously, there’s the Nike deal with Oregon or Ohio State and Under Armour’s deal with Maryland, but nothing like what we wanted to do.

They’ve invested millions in this idea of putting out information that will make sport better, make people in sports better, make the entities better and make the world better as a result.

TSL: That’s pretty remarkable because sport definitely brings people together and has the power to change the world. When you think about the journey, from dreaming about playing in the NFL to having the epiphany of moving the needle to provide greater access and opportunities through sports, what does that conjure up for you?

KS: This whole thing is a journey. Six or seven years after getting out of law school, I was thinking, “What am I doing?”

I had a conversation with my mother when I was out there hustling, representing my athlete clients and doing the lawyer thing. And she says, “What are you going to do with your life?”

I said, “I’m doing it!” She said, “No, you seem to like this teaching thing, why don’t you look at doing that full-time.”

I hadn’t really thought about it. I’d been teaching some classes part-time, and that’s when the Wharton opportunity came up. And it was in those first couple of years when I got that call from the baseball folks.

I began to see that there was something that I could really do, but I also had to be successful in the professor business, so that’s what motivated me. I said, “I gotta do this publishing and all this other stuff,” and so that’s really how it all came together.

TSL: That’s what they call serendipity.

KS: It wasn’t a plan. But I began saying to myself, “What do I want to do? I’m only going to do the stuff that I want to do. And I want it to be impactful. I don’t want to waste my time doing things that are not going to do something for somebody else.”