Stephen Curry. Damian Lillard. Russell Westbrook. Tony Parker. Chris Paul. Mike Conley. Kyrie Irving. Rajon Rondo. Derrick Rose. John Wall. Ty Lawson. Jrue Holiday. Kyle Lowery. Goran Dragic. Jeff Teague. Kemba Walker. Eric Bledsoe.

In case you don’t know, I toss those names out to make a point that should be self-evident – that we’re living in the greatest era of point guard play, in the aggregate, that the NBA has ever seen.

As tonight’s Western Conference Finals between the San Antonio Spurs and Oklahoma City Thunder tips off, the supreme magnificence of the lead guard position will be crystallized in the matchup between Tony Parker and Russell Westbrook.

It’s a fascinating examination of two contrasting styles: Westbrook’s explosive fast-twitch fibers, violent assaults on the rim and physics-defying, Matrix-like acrobatics diametrically opposed against Parker’s cerebral ruminations, choreographed crisp ball-movement and the surgical incisions that he inflicts on a defense with a mid-range, floater and points-in-the-paint game that is more efficient than a Toyota Prius.

Around this time of year, we’re always reminded about the great playoff performances of point guards from years past. Unfortunately, it’s always the same Usual Suspects that get paraded in front of us. We’re constantly fed a steady diet of Isiah Thomas’ and Magic Johnson’s amazing accomplishments.

Every now and then, an edified person will point out that you can’t talk about great NBA point guards without mentioning Oscar Robertson, Walt Frazier, Earl Monroe and Gary Payton. Steve Nash and Jason Kidd will also get their props as two of the game’s most recent legends at the position.

But for some reason, unless they’re a true connoisseur of the game, most folks have to be nudged toward one of the most remarkable floor generals in league history, Nathaniel “Tiny” Archibald. Following along the Usual Suspects theme, Tiny is the lineup’s Verbil Kint.

He’s slept on in favor of the figurative McManus’, Keaton’s, Fenster’s and Hockney’s. But it’s only through a more thorough examination when we realize that he’s actually Keyser Soze, a man whose stunning influence and ruthlessness in the delivery of his craft have created his mythical and legendary status.

As a skinny kid that always looked much younger than his actual age, Tiny insulated himself from the worst elements of his South Bronx neighborhood with a ball and a hoop back in the day.

“We paid $109.00 a month rent and got the neighborhood for free,” he once said. “We were overcharged for both.”

Born and raised in a two-bedroom apartment in the Patterson Projects, the oldest of seven kids, Tiny lived and breathed basketball. When he wasn’t outside playing on the playgrounds, he was the first to arrive at the Public School # 18 Community Center when the doors opened at 3:00 PM. More often than not, he was also the last to leave.

Mentored by Floyd Lane, a former great lefty for the City College of New York (CCNY) team that captured both the NIT and NCAA college basketball championships in 1950, Tiny, as an awestruck kid, would watch as Wilt Chamberlain, Meadowlark Lemon, Satch Sanders and others popped into the P.S. 18 gym whenever they were in town.

In the process of watching the game’s legends up close, and competing against older players and peers on the New York City playgrounds, Tiny acquired a ridiculous conglomeration of handles, head fakes, body shakes, feints, a jaguar-like burst and a smooth feel for the rhythms, nuance and personality of every game situation.

Before suiting up for DeWitt Clinton High School, where he captured the city public school title in 1966, and before Jay Z popularized the phrase, the streets were already watching.

One fall day in 1964, while shooting jumpers at a court in the Patterson Projects, Tiny heard about a game taking place at St. Mary’s playground. Squeezing through hundreds of spectators to get a front row seat, he saw the incomparable playground legend Earl “The Goat” Manigault utilizing his 52-inch vertical leap to ram down two-handed, backwards dunks in the faces of overwhelmed opponents. He observed another asphalt legend from the Uptown milieu, Herman “Helicopter” Knowings, swatting weak shots out of the park and into the adjacent street’s congested traffic.

When one team was suddenly in need of a guard due to an injury, Tiny popped out onto the court as the crowd, and some players, laughed at the diminutive, bony, baby-faced adolescent. But once the rock was in his hands, the laughing transformed into a roaring ovation.

Starting one sequence with his dribble at the top of the key, he whisked by a startled 6-foot-4 college player with a sudden burst as he drove down the right side of the lane. Floating towards the hoop, he somehow slid the ball between the Helicopter’s flailing, windmill arms and flipped in an elegant lay-up that made the crowd go bonkers.

Among his family and friends, he was known as Tiny because he inherited the nickname from his father, who was known as “Big Tiny.” But in the basketball community, he was anointed with his own moniker, “Nate the Skate.”

Tiny almost dropped out of high school when bad grades and truancy kept him off DeWitt Clinton’s varsity team as a sophomore. Encouraged by his basketball mentors, who knew that his talent could elevate him out of the squalor and poverty of the neighborhood, Archibald returned to school.

As a junior, he didn’t see much playing time at the beginning of the season, but his quickness, shiftiness, speed and passing ability could not be ignored. By his senior year, after delivering the school a coveted city championship, he was named to the prestigious All-City team.

“I had to make changes,” Archibald once said. “I didn’t know where I was going. I didn’t know I was going to the NBA, going to [college]. People saw something in me that I didn’t see.”

Due to his less-than-stellar transcript, a major college scholarship was not forthcoming, so Archibald packed his bags for Arizona Western Community College. He hit the books, flourished on the basketball court and earned a scholarship to the University of Texas, El Paso.

Away from the spotlight, while the nation was fixated on what another playground disciple from New York City named Lew Alcindor was accomplishing at UCLA at the time, Archibald prospered. But his exploits were an afterthought to the scoring and passing wizardry of “The Pistol”, Pete Maravich, at LSU in addition to the video-game-like numbers that another diminutive guard, Calvin Murphy, was putting up at Niagara University.

Maravich and Murphy were selected ahead of him in the 1970 NBA Draft, as Tiny was picked by the Cincinnati Royals in the second round. But he outplayed both of them while averaging 40 points in various post-season all-star games.

Tiny was named MVP of the East/West game in Louisville. At the Aloha Classic in Hawaii, he spontaneously combusted for 51 points while earning that event’s MVP honor as well.

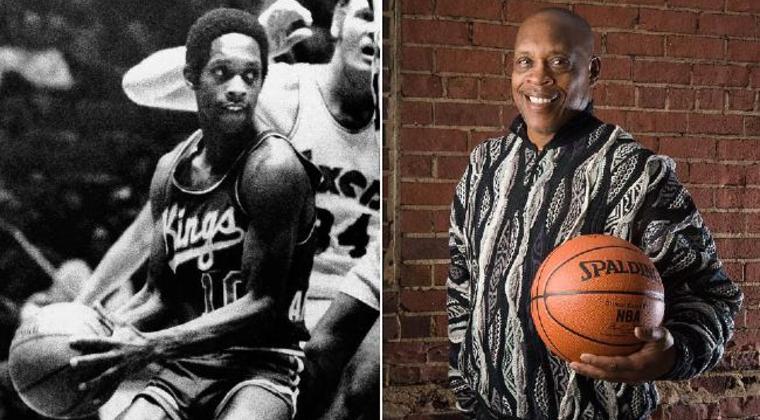

After taking two years to adjust to the pro game, Tiny blossomed during his third pro season, when the franchise relocated to Kansas City. At the age of 24, he averaged 34 points and 11 assist per game, leading the league in both categories. It is a feat that has never been duplicated since.

Nine years later, playing alongside a young Larry Bird, Cedric Maxwell, Robert Parrish and Kevin McHale in 1981, Nate “The Skate” was the floor general and orchestrator for the World Champion Boston Celtics.

And yet, despite his stature and celebrity, Archibald returned to the rugged New York City streets every summer to work with, mentor, encourage and elevate kids through the sport that had given him so much.

His legacy, and impact on today’s game, is much more pronounced than some might realize.

While serving as an assistant coach at the University of Texas-El Paso, Tiny mentored the great Tim Hardaway, who spread the gospel of the crossover along to Allen Iverson, whose cultural significance and athletic aesthetics contributed to the move’s ubiquity in every floor general’s arsenal today.

“That’s the man right there,” Hardaway once said. “He had a lot of flair. That’s one of the reasons I went to UTEP, because Nate Archibald went there. He was there for two years as an assistant coach and taught me a lot about how to play the game.”

Archibald also returned to school to complete his requirements for a Bachelor’s Degree, taught in the New York City public school system and went on to earn a Master’s Degree from Fordham University. A few years ago, he began working towards a Ph.D. in Education.

His contributions to the game are immense. At a time when the small man was being phased out of the pro game, Tiny proved that a tape measure could never measure someone’s worth, fortitude, power and fate. His accomplishments ensured that there would always be a place for a talented, creative, speedy, intelligent little man with a big heart.

Allen Iverson, Isiah Thomas, Mahmoud Abdul Rauf, Muggsy Bogues, Chris Paul and the rest of the little-big men should send Tiny a percentage of every dollar they’ve ever earned on the court, because he paved the way and opened the doors that they were eventually able to walk through.

So as we watch in awe and admiration as Tony Parker and Russell Westbrook do battle in the Western Conference Finals – when they execute and convert a mind-boggling, high-degree of difficulty foray at the rim that makes us randomly jump up and shout, “In Da Face!!!” – we should take a few moments to appreciate the evolution of the NBA point guard over the years, and those who built the foundation of what we’re seeing today.

Yeah, Magic Johnson, Isiah Thomas, Walt Frazier and Oscar Robertson should be some of the first names that come to mind. Along with Tiny Archibald’s.