Despite the complaints by players and coaches that the National Football League is becoming too soft, and despite the fact that the league’s marketing department loves to play up the family fun aspect of professional football, and despite the fact that there are children as young as five years old playing it, football is a violent sport. For more than a century, the biggest, fastest and strongest athletes in their respective age groups have lined up across from one another and have attempted to tear one another limb from limb within the concept of the game. For years, long before Ray Rice and Jovan Belcher’s grandparents were even born, professional football players have had a reputation of being fiery, pugilistic and tending to lend themselves toward violence if goaded, prodded or otherwise “provoked” to do so.

As professional football became increasingly blacker in its demographics, the narrative has often strayed to frame instances of violence among NFL players as a problem of upbringing and poor decision making. But recent medical revelations have revealed a flaw far more dangerous than anyone who has played the game could have ever imagined when picking up their pads to play Pop Warner football in their childhoods.

Within our lifetimes, there have been numerous, previously inconceivable instances of violence involving NFL players. OJ Simpson, Ray Lewis, Rae Carruth and Aaron Hernandez were each accused of murder, Carruth and Hernandez were actually convicted of these dark deeds. The tragic murder-suicide involving former Kansas City Chiefs player Jovan Belcher and fiancée Kasandra Perkins is still fresh in our minds. There’s also the historical precedent of hundreds of domestic violence cases in the NFL since 1980. While the Ray Rice situation is the most recent, the issue of domestic violence has long been overlooked and under punished by the NFL. The mantra of “boys will be boys” was often the underlying context for these acts not being reprimanded to the extent they otherwise may have been had they occurred among members of the general population.

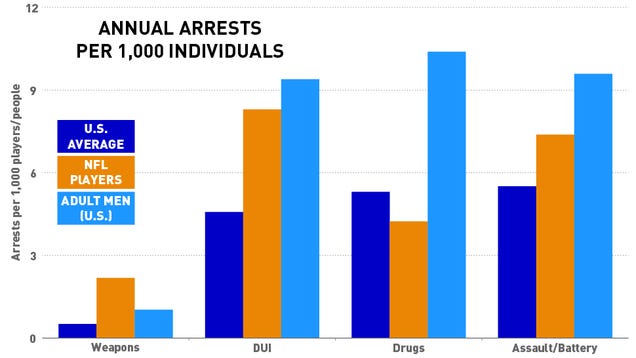

It’s almost as if we all expected football players to get violent off the field more often than the average American citizen. However, even that is something of a misnomer. The NFL is a league of adult males. Adult males are a demographic that is more likely to be arrested than any other. So the fact that an occupation that is exclusively male is arrested for weapons charges, assault charges and drug charges is somewhat overstated. However, when comparing the arrest rates of NFL players with that of adult males in the general population we find NFL players compare very favorably to the average male in the U.S.

(Chart courtesy of Deadspin)

NFL players are less likely to get a DUI, less likely to get a drug charge, and less likely to receive an assault charge relative to their male counterparts in the general population. To many It is something of an eye-opener (and to some, a relief) to see that a league that is mostly comprised of young black men is actually less criminally-inclined than the significantly whiter general population.

Despite those numbers, the general belief that NFL players are violent time bombs on the verge of exploding at any moment is fairly common in this age of social media, candid cameras and security breaches. The (sad) perception is that America doesn’t really care that the average Joe is robbing, stealing and killing from a news coverage perspective. It only becomes a story when a person who is believed to have some kind of cultural merit is committing them.

Last year, the body of Jovan Belcher was exhumed from its resting place and his brain was tested for CTE. It was found that he did in fact suffer from the disease. CTE, or Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy. It is a degenerative brain condition that is known to be caused by repeated blows to the head. Though an official diagnosis can only be done posthumously, victims’ symptoms include memory loss, aggression, confusion and depression. In the past, it was believed CTE was caused by multiple concussions over the course of an entire football career, which includes high school and college for the vast majority of NFL players. With prior research models concluding that CTE takes place over the course of a lifetime, the National Football League has been able to shrug off complete responsibility for the debilitating effects of CTE on retired NFL players, and has been doing so for at least 20 years.

However, with the recent revelation that CTE can manifest itself in players as young as 17 years old and that the accumulation of less serious head injuries like sub-concussions can also lead to CTE, every player at every level of the game must take a hard look at himself and the sport of football. Every football parent must recalculate their willingness to allow their child to be put in harm’s way, and every coach must decide whether a game, no matter how beautifully composed, is worth a lifetime of pain, confusion and the risk of premature death to the player.

According to some estimates, Three in ten former NFL players will face a post-career life with a moderate cognitive disability. As recently as 2012, so-called "experts" cautioned the public against connecting the obvious dots between the suicides of NFL players Andre Waters, Junior Seau, Dave Duerson, Paul Oliver and Jevon Belcher and CTE. One of those experts was Chicago-based neurosurgeon Julian Bailes. He is one of those who doubted the connection between CTE and player suicides and expressed that viewpoint repeatedly during a 2012 episode of ESPN’s Outside the Lines titled “Football at a Crossroads”. It should be noted that Bailes is the former lead surgeon for the Pittsburgh Steelers as well. Does that make his opinion moot? Of course not, however it is indeed worth mentioning a potential conflict of interest in the good doctor’s opinion.

Some individuals have long said that steps should be made to make football a safer game without changing its fundamental makeup.

But is it even possibly to legislate head to head collisions in football? Unfortunately, there is no safe version of football. Players of all ages are going to get their bells rung on a game to game basis and their brains will continually be subject to damage throughout their careers, even if they never make it to the NFL. The available data says this ringing might last a lifetime for some; thus, a life in football could result in a death caused by football. Despite the small potential for a lucrative career, a poor quality of life filled with pain, emotional instability and symptoms likened to Alzheimer’s disease are a daunting conciliation prize.

Enough with the double talk, enough with the “devil’s advocate” speak. Football is obviously far more dangerous than anyone could have ever imagined. Team owners and their cronies can no longer hide behind ambiguity. The accumulated facts say that a full third of all NFL players will eventually suffer from CTE or some similar brain ailment. No NFL player should be shamed over holding out or demanding more money ever again. He’s not only putting his body on the line, but his brain and his life as well. The increased risk of domestic violence and suicide needs to be factored into every contract or collective bargaining agreement from here on out. The recent $765 million settlement between the NFL and 4,500 former NFL players needs to be revisited as well. That one-time Herculean figure now looks miniscule in comparison to the risk.

A risk that everyone who plays the sport, and anyone who allows others to play the sport, has to seriously contemplate.