This is Part II of the final installment of our series entitled, “Ivy League Hoops: Ahead of the Curve in Coaching Diversity.”

You can read Part I of the Jerome Allen story here

PART II

TEAM MEAL

After the shoot-around, the players and coaches disperse in various directions. Allen slides out of a Palestra back door to jump into his nondescript, late model, white Toyota Camry.

Dont say anything about my car, he tells the group of four waiting to get in as he removes a child safety seat from the rear and scoops up some bottles of Powerade that rest on the seats and floor mats.

The team meets back up within minutes at Smokey Joes on the other end of campus for their pre-game team meal. Smokes, as the establishment is known on campus, is as much a Penn institution as the Wharton School. As the team eats a tasty chicken parmesan and pasta meal with house salad on the side, Allen looks earnestly across the table in the dark, cozy dining area at Phil Samko, an athletic trainer at Penn since 1985 who everyone calls Sam, and asks him if hes seen the latest news reports.

Hey Sam, you heard about the confrontation that Tom Brady and Bill Belichick had the other day, right?

Samko either doesnt hear him, or pretends not to.

Yeah Sam, its been all over ESPN today, Allen continues, while looking down mischievously and cutting the chicken on his plate. It got ugly. They traded Brady straight up for Andy Dalton.

Samko, a stocky Massachusetts native with the bearing of a Marine, looks at Allen for a quick moment and says nothing. Allen glances up at him, trying to keep a straight face, but smiles wide.

Nah, you know Im messing with you, Sam, he says.

By 4:00pm, when the players have cleared out after being reminded to be in the locker room at 5:30pm, Allen heads back to his beautiful and tidy office in the recently renovated Hutchinson Gymnasium, which has since been renamed the Tse Ping-Cheng Cheung Ling Sports Center.

He eschews his spacious and neat desk, preferring to sit on a comfortable blue couch with his back to the large glass windows that overlook the teams dazzling new practice facility. Pictures of his mom, his wife and children and of his last team meal as a Penn player, along with photos from the teams recent summer trip to Europe, line the shelf on the oak cabinet against the wall behind his desk.

Copies of Forbes Magazine, Entrepreneur, Fortune, Inc, GQ and Fast Company, are neatly layered on the glass table in front of the couch. Aside from the basketball pictures and memorabilia lying around, the office could easily be mistaken for that of a high-level corporate executive.

Its difficult for him to keep his mind from racing on game days. Sometimes, hell sneak into a movie theater alone earlier in the day, or hell cue up his turntables at home, slide on some headphones, and DJ a classic Hip Hop and R&B set for a few hours before heading into the office.

With about an hour to himself before walking over to The Palestra next door, he lounges on the couch and flips open his journal. He sits across from the large whiteboard hanging on the wall that is normally filled with practice plans, diagrams, important dates and notes, along with some sayings that he favors, like, This is my season for grace and favor. I have a seed in the ground.

He meditates on the written words inside the leather-bound notebook that he cradles in his large hands with care. Hes working on a book, tentatively titled, The Value of Public Space. He stares and concentrates while reading some words aloud: painful and cathartic words that touch on his upbringing, the pain and complexity of his relationship with his father, his adoration and admiration of his mother and his unequivocal love and devotion to the town that shaped and sharpened him.

THE MAKINGS OF A PHILLY POINT GUARD

Philadelphia might be the fifth-most-populous city in the United States and the second largest city on the East Coast, but the basketball community that has produced some of the games all-time greats like Wilt Chamberlain, Earl The Pearl Monroe and Dawn Staley, is incredibly small. There are six schools within the area that compete in Division I basketball: Penn, Drexel, LaSalle, Villanova, St. Josephs and Temple.

This is a college basketball town and everybody here follows the game, said Allen.

(Photo Credit: Penn Athletics)

As a young teen, Allen became immersed in the towns incubators for promising basketball prospects like the legendary Sonny Hill Summer Leagues, striving to pattern his game after the college and pro players that were a few years older than him, guys he saw playing on the same courts that he did during the summer. A few hours after his games were over, hed still be in the gym, watching guys like Pooh Richardson, Mark Macon, Doug Overton, Lionel Simmons, Hank Gathers and playground legends like Fat Eye Watson, among others.

Philadelphia is a basketball hotbed, said Allen. I was just trying to stay in the gym and compete, for nothing else but bragging rights. Everybody cared about winning. I looked up to the older Philly guys. I loved the game so much, that watching those guys and wanting to pattern my game after them drove me to want to be able to hold my own, no matter who I was playing against.

If you were really in love with this game like I was, and you wanted to be a part of the Philadelphia basketball fraternity, you were going to have to step your game up, because on any given day, nobody cared about what school you went to or what you did the night before, he continued. Everybody was trying to go after you right then and there. By accident, I became good.

Part of the reason for the collective success of Phillys basketball players, in college and beyond, is due to the competitive philosophy of the older guys having a civic duty to sharpen the skills of the younger guys coming up after them.

Those summer workouts keep the heartbeat going, said Allen. You have the high school guys training with the college and pro guys. Thats the best thing about Philly. We feel responsible for helping the next guy. Its a true fraternity in that in all of the drills and pick-up games and workouts, theres a fusion of the older guys being responsible for the younger guys.

In terms of his formal and social education, Allen excelled at Episcopal in many ways. In addition to being one of the states best high school quarterbacks and also being ranked as one of the countrys top ten guard prospects in basketball, he invested as much of himself as possible in order to not only handle the schools academic rigors, but to excel through them.

He also formed lasting friendships. In the same way that his rich friends invited him to their homes, he invited them to his. If one of them slept over at his spot on Germantown Avenue, Allen would give them the luxury of a back-room couch while he curled up on the floor.

There were times, though, where he was irked at having to straddle the fence between the hood, and his academic world of privilege.

There were times when my mom didnt have the money to give me tokens to get to school, said Allen. It might be a Wednesday and she would say, I have enough to get back and forth to work and enough to get there the next day before I can go to the check-cashing place and come home with some money. People would ask me, Hey, why werent you in school the past few days? What was I supposed to say?

His high school coach, Dan Dougherty, who also doubled as his math teacher, became another significant mentor in his personal and athletic development. Allen would become a three-year varsity starter for Coach Doc at Episcopal. It was under Doughertys stewardship that he embraced other aspects of the game, besides scoring, developing into an elite passer and on-ball defensive hawk.

Temples John Chaney and John Calipari, the current University of Kentucky coach who was then at the University of Massachusetts, were among the many college coaches who courted him extensively.

Allen would look into the stands at his away games, marveling at the fact that his mother managed to get there.

Shed be sitting outside in the freezing cold at my football games, or shed show up at my basketball games, and I dont even know how she managed to get to places where the buses didnt even run, said Allen. She must have been walking for miles to get to some of those places, just to show me support.

During his college recruitment, when one of his classmates suggested that he think about playing at Penn, Allen was initially dismissive of the thought.

His mother went to Penn, as well as his uncle and grandfather, said Allen. When he suggested that I should go there, I was offended at first, thinking that he was telling me that he didnt think that I could play at the highest level. But he was connected to what this place was all about, what this brand represented. I thank god that I had people in my life that told me what I needed to hear, not what I wanted to hear.

The recommendation letter that Episcopal sent to Penn still encapsulates who he is. Three years ago, Episcopal thought it was taking a risk, a section of the letter reads. We have been proved wrong. Jerome Allen is, in every way, one of our greatest assetsA superb athleteyes, for that he is most obviously gaining glory. But beyond his athletic gifts is amazing character. His appreciation for life is broader and deeper than most people who have been given every privilege. Jerome Allen represents not only the scholar-athlete that is an ideal of our school but also the marvelous potential that exists in our society if we give it half the chance.

Allen was torn when making his college decision. He thought about playing in the ACC with Wake Forest. John Chaney was a local legend at Temple that was sending guards like Aaron McKie and Eddie Jones into the NBA. Calipari was constructing a power at UMass that would soon make a push into the Final Four. But there was something about Penn that tugged at him.

I based my college decision on a couple of factors, like where could I have the most impact as a freshman, said Allen. But I started to think about the fact that I grew up in a household of 19. My fathers a drug addict, my mom dropped out in the 10th grade, my grandparents didnt go past the 6th grade, that no one in my family graduated from college. And here I had this opportunity to go to the Ivy League.

I watched my mom slave and struggle to be able to take care of her kids, he continued. I dreamed about playing in the NBA. I mean, what kid didnt? But I wanted to go somewhere and get a degree that would enable me to get a good job one day so that I could take care of my mother.

Allen told his friend, teammate and Episcopal classmate, Dan Liebovitz, who was most recently a member of the Charlotte Bobcats coaching staff last year, that he wanted to one day become an accountant. He asked his buddy, Are you sure that if I go to this school, that Im gonna be able to get a good job and be able to take care of this lady?

Jerome, if you have a chance to get in Wharton, you can get any job you want, Liebovitz told him.

Once he told me that, that sealed the deal, said Allen. I made the decision right there. Penn was where I was going to school.

HURRAH FOR THE RED AND THE BLUE

During Allens freshman year, Penns then head coach Fran Dunphy was in the process of rebuilding a program that, prior to his hiring in 1989, had just one winning season in its previous six. The Quakers finished 16-10 during Allens first year on campus, a seven-game improvement from the year before. But his transition to college basketball was not always smooth.

I was this kid from North Philly, coming in with all these accolades, a tattoo, all these parts shaved into my hair and all of these press clippings, said Allen. My selfishness at the time, because were all selfish by nature to a certain extent, wouldnt allow me to understand what was going on at first. My initial approach, walking into the family, was based around what was tangible to me, like getting my shots and my playing time.

But Dunphy, or Coach Dunph as his players called him, had a plan.

I was thinking, I coulda went to North Carolina, Wake Forest or Temple. Why do they have me sitting behind this guy that Im destroying every day in practice? said Allen. But Coach Dunph knew what he was doing. He knew what it would take in order to build what he wanted. He told me, Just because you were the 9th ranked guard in the country, youre not bigger than anyone else. This place is bigger than you and if you dont learn to not only respect your position, but also how to best service this group, then we will never win.

Allen watched how relentless his teammate Paul Chambers practiced. He swallowed his pride while lugging teammate Vince Currans bags. All year, he had to fetch water and do other freshmen tasks, just like all of the freshmen that came before him, regardless of how talented he was.

Hed call his mom to complain, but she never joined in the pity party.

I just told him to be patient and keep working hard, that his day was coming, said Janet Allen. I would remind him, every day that better days were ahead. I kept saying, Watch, boy, Im telling you. Keep working. Youre going to get your turn.

During one practice in late December of the 91-92 season, Allen had an epiphany.

If we were running sprints and the clock was getting to one second and he wasnt at the line, Paul Chambers would dive across the line, said Allen. Wed be exhausted and he always seemed to find that extra umph to push his body through. I complained and thought that I was working hard, until I saw somebody who was truly working hard.

He also thought about his mother and the sacrifices that she continued to make.

I realized that I was sitting there complaining about playing time and not getting enough shots, and my mom is up at 4:30 every morning, traveling long distances on public transportation to clean hotel rooms, said Allen. She was committed to doing what she had to do. So between watching how Paul Chambers gave everything he had in practice, and thinking about my mother, that helped my mind state. I just said, I can continue to complain about what Im not getting, or I can do something about it and just be 100% ready for when that opportunity comes.

As the season progressed, he was inserted into the starting line-up.

I gradually learned what it took to win, said Allen. It was very tough at first. But I learned that before you can win, everybody has to have a spirit of humility. Everybody has to understand what their role is, in terms of the community and out on the basketball court. I learned that chemistry is so underrated, that its the single most important thing, to have a collective effort in any group setting. I learned that if you have the right chemistry and the right people around you, you can go wherever you want.

The Penn basketball program went on to re-write the record books over the next three years as Allen blossomed into one of the best players in the country.

But as the saying goes, All that glitters aint gold.

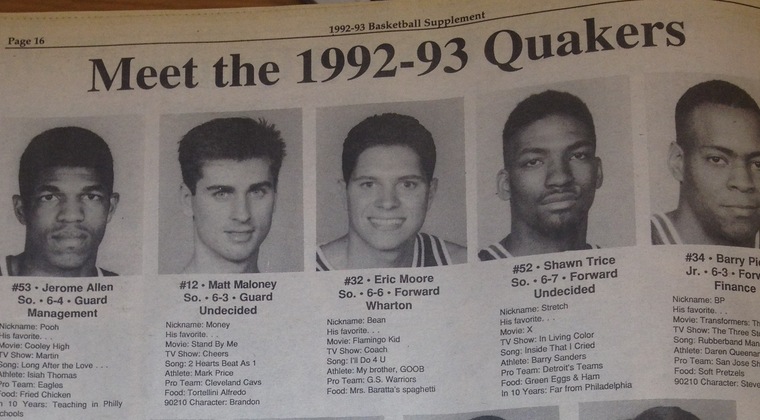

(Photo Credit: Daily Pennsylvanian)

During his sophomore and junior years in 92-93 and 93-94, when Allen and Matt Maloney were proving to be one of the countrys most dynamic and effective backcourts in any conference, leading the Quakers to records of 22-5 and 25-3, Allen was a crowned prince on the Philadelphia hoops scene. His face was ubiquitous in the newspapers and on the sports segments of the evening news.

In the midst of all of that, a familiar face began showing up at The Palestra.

My dad started showing up at the games, said Allen. Id see him in the stands. Hed ask my mom for a couple of dollars and by halftime hed be gone.

One day during his junior year, he cashed his work study check and looked at the $70 in his hand. It was a game night, his mood was buoyant. Normally, hed run downtown to the Wannamakers department store and purchase a jazzy shirt or two that he could wear that weekend to some of the big parties on campus at Bodek Lounge in Houston Hall or at one of the frat houses.

As he walked along the red bricks of Locust Walk, passing the grandeur of the ivy-covered gothic brick buildings, the college green and the architectural masterpieces of College Hall and the Fine Arts Library, he decided to do something different.

I was thinking that I might see my dad, said Allen. I was thinking that if I saw him, I was gonna give him a few dollars.

Dunphy required his players to be in the locker room at 5:30pm on game night, but Allen always arrived early. No later than 5:10pm, hed be on the court, by himself, getting up some shots, breaking a sweat, finding his rhythm. After warming up with the Cathedral of College Basketball all to himself, he went into the locker room to get changed into his uniform.

As the fans began filing into The Palestra, as the buzz in the old building began to build, as the Quakers were about to take the court for their lay-up lines, the team equipment manager came into the locker room and pulled Allen aside.

Hey Jerome, does your dad need money, he was asked.

Defensive, and already embarrassed that his disheveled dad showed up on some game nights, Allen responded tersely, with more than a bit of North Philly in his voice. What? Whatchu askin me that for? Whatchu talkin bout?

Because your dad is standing outside of the main entrance right now, the manager told him. Hes out there panhandling, asking people for money as theyre coming into the game.

The words felled him like a hail of bullets. The 6-foot-4, mercurial guard, one of the countrys best college players, an NBA prospect, found himself on his knees, sobbing uncontrollably.

Coach Dunph came back to talk to me, but he didnt know what to say, said Allen. I mean, what do you say? He went and got my mom. She asked me what was wrong and when I told her, she flipped out. She went out there and told him to stay away from us. I was so hurt, so embarrassed, so ashamed.

I look at it now, and realize that its a part of life, he said. He was on that dope. He was really rumbling with something powerful. That dope is crazy.

To Be Continued…PART III

Series Intro: Ivy League Hoops, Ahead of the Curve in Coaching Diversity