This is the fourth and final installment of our series entitled “Ivy League Hoops: Ahead of the Curve in Coaching Diversity.”

PART I

SHOOT-AROUND

The industrial-sized fans that squat on the four corners of the floor at The Palestra, the legendary hoops shrine at the University of Pennsylvania that is commonly referred to as the Cathedral of College Basketball, are whirring loudly. The humming purr of the blades hovers over the symphony of rubber soles squeaking on the hallowed hardwood, the thud of bouncing basketballs and the sweeter-than-Kool-Aid sound of swishing nets.

Its shortly before 2:00pm on Friday, February 21st, as tornado warnings and the distant rumblings of thunder hang in the humid, dreary, rainy Philadelphia afternoon air. Moments before the Penn mens team begins its scheduled shoot-around, head coach Jerome Allen is standing at the half-court stripe, near the out-of-bounds line, draped in a loose-fitting black Nike sweat suit.

Hes not Coach in this moment, simply Pooh, a long-limbed, angular hoops junkie from North Philly whose childhood nickname has followed him into adulthood. Cradling a basketball, he eyes the rim, which stands 47 feet away. Easy shot, he says to a cluster of players milling around.

You cant make that, one of them says.

You wanna bet? Allen asks.

How much? The players reply sounds valiant, albeit with an audible hint of uncertainty.

How much you wanna lose, Allen inquires mischievously, rhetorically.

He lazily elevates a mere few inches off of one foot, with his other knee raised in the air. The motion is fluid and smooth as the ball spins softly off of his fingertips with perfect rotation. It makes its way toward the basket in an ideal parabola, finds the back of the rim and tenderly bounces around, before rolling out of the cylinder. He stares at the rim, head cocked to the side with his lips pursed, before sucking his teeth, shaking his head and giggling.

At 2 oclock on the dot, Quakers assistant coaches Scott Pera and Ira Bowman begin yelling, Baseline! Baseline! Baseline!

The players jog toward the basket, repeating the word over and over while clapping and lining up. The starters, wearing blue practice jerseys, watch as a team of substitutes wearing grey tops are summoned to run through the offensive sets that Harvard, tonights opponent, prefers to run. The blue team steps in after a few rotations to play defense.

Allen is still in the corner where he missed his half-court shot, but the smile and playfulness that permeated his face just minutes ago is gone. Hes on one knee, staring, concentrating and studying minute details. Hes watching and critiquing things that the casual fan never sees, like weak side defensive rotations, the width and angle of a players stance when setting a screen and the off-ball action.

Seconds later, hes on the other side of the court, his long, slender fingers snaking up the side of his face as his chin and goatee are obscured by the webbing between his right thumb and index finger.

Pera, Bowman and Allen point out the tendencies of each Harvard player as the scout team mimics the Crimson offense: who likes to shoot from where, who will drive to the basket after curling off a screen, the specific areas where certain opposing players are comfortable shooting from, who is ineffective spinning to the left, etc.

When one starter goes underneath a pick, Allen springs toward the players, his first step still ripe with remnants of the blow-by speed that he was once known for during his playing days.

When youre guarding Rivard, do not go under the pick because hes looking to shoot immediately off the catch right here, Allen says, referring to Harvards three-point rifleman Laurent Rivard. Get over the top of that pick and immediately get that hand up before he catches the ball. Hes not looking to put the ball on the floor right here.

Allen, Pera and Bowman reiterate the point on several occasions. They review the tendencies of every weapon that Harvard has, along with how to effectively defend their various sideline and baseline inbound plays, before the starters begin running through their own offensive sets.

They yell out 52, 52, 52, Runner, Runner, Runner , 1-3-1, 1-3-1, 1-3-1 and Elbow Cross, Elbow Cross, before scurrying in choreographed full and half-court patterns, filling lanes, setting and coming off picks, and crisply swinging the ball to the desired spots within the offensive flow where they hope to have an advantage tonight.

Miles, you know all of this stuff, he tells senior, Second-team All-Ivy guard Miles Jackson-Cartwright. You know everything. You have to let these guys know whats going on and what theyre supposed to be doing, Allen says calmly.

They finish up with a shooting contest that the starters lose. The subs smile with satisfaction as theyve avoided a penalty of pushups that close out the practice. As the team converges on the blue and red P at half-court, Bowman reminds the injured players that their academic requirements take precedence over shoot-arounds and walk-throughs.

When Bowman finishes, Allen speaks softly and quietly, but the urgency of his words is apparent by his furrowed brow and moderately forceful body language. You have to lean in to hear him above the drone of the fans, which have been losing their battle with the gyms humidity for the entire practice.

Remember, you control your own destiny, says Allen. You cant change yesterday, he states with more emphasis, looking around the circle and into the eyes of his players. Those words seem to come from an unseen inner space. A place where hurt lives.

But you can do something about today, he says.

The players put their hands together and shout, One-two-three, TOGETHER!

YESTERDAYS

Jerome Allens yesterdays are filled with victories and accolades that are too numerous to mention. He is one of the greatest players to ever come out of Philadelphia.

Any coach that he ever played for will tell you that he cared about his team, that he sublimated himself for the good of the collective, that he took immense delight in defending and sharing the ball. Theyll tell you that he hated to lose.

Theyll also inform you that he was a chameleon on the court. He could blend in and fulfill his role within the team construct, playing flawless textbook ball. Simultaneously, he had the ability to freelance effectively with a mesmerizing handle and playground boogie.

If the offense broke down, as the shot clock ticked away, he had the ability to improvise like Thelonious Monk, with an un-teachable wiggle that could wobble the most sincere defender. When he attacked the rim at high-velocity, with a suddenness and smoothness that could be shocking to the uninitiated, hed often leave the most diverse crowd unintentionally uttering, Oooooooh! in unison.

He once appeared in a Slam Magazine photo spread, posing on an outdoor playground blacktop with a fitted Phillies baseball cap tilted to the side and his white, loosely laced Nike Air Force 1s sparkling underneath his baggy jean shorts. The magazine was paying homage to the Pooh Allen, his eponymous crossover that is still an urban legend on the citys asphalt.

A member of the Big 5 Hall of Fame, he is considered by many to be the best player to ever wear a Penn uniform, where he won three consecutive Ivy League titles, with an amazing three-year undefeated run through conference play from 92-93 through 94-95, before moving on to the NBA and a pro career in Europe that spanned 14 years.

But those yesterdays, along with the immense joys and accomplishments, were also filled with their fair share of shame, hurt, anger, pain and bitterness.

His grandparents moved from Georgia and settled in North Philadelphia in the 1940s as part of the great northern migration of African-Americans who left the oppressive powder keg of the south in search of better jobs, living conditions and opportunities. By the time Allen was a young boy, the dream of what awaited up north, what many termed The Promised Land, proved to be more of a nightmare for many families.

The North Philly and Germantown neighborhoods where he was raised are slices of the city unlike the Liberty Bell, the Museum of Art and Independence Hall that do not appear on postcards. They are poverty-stricken areas that are flooded with narcotics and characterized by blight, inordinate rates of crime, addiction and homicide.

Allen grew up living with 18 relatives in a 5-bedroom row house that his grandparents owned on Germantown Avenue, on a block of boarded up homes and vacant lots. He slept in the same bed with his sister until he was 15 years old. His mother and aunt initially nicknamed him Pooh-Pooh, which was later shortened to Pooh.

He was my little teddy bear, said his mother, Janet. Young Pooh was always precocious and ever since he was about three years old, he always had either a football or a basketball in his hands.

Sometimes, when the electricity was cut off, he knew that his aunt would go outside and start messing with some wires. Within a few minutes, the lights would miraculously come back on.

If there was no heat, somebody would come over with a kerosene heater and the family would migrate and huddle in one room. If there wasnt any hot water, a hotplate would appear and the family would heat cold tap-water in large pots. In the humid Philly summers, with no air conditioning, hed attempt to fall sleep with a cold washcloth on his face. The refrigerator was empty more often than not. Sometimes, his relatives sold drugs out of the house.

I just thought that was the norm, said Allen. I didnt know any different. Obviously, we had a limited amount of resources, but I felt like we had everything. Everybody pitched in to make sure we had a roof over our heads.

The neighborhood we lived in was really, really rough, said Janet. We did the best we could and got by on what we had. Philly is a rough town. A lot of his friends have passed away over the years. Through it all, god has blessed my child.

We adapted to whatever the situation was, said Allen. I didnt think that we were living in extreme poverty. You only know what you know. And we had fun.

But as a kid, Allen saw many things that could not be characterized as fun. The constant specter of violence in the streets, the continuous wail of sirens and persistent gunfire were also a daily reality, despite the love and laughter that messaged his family through lifes troubles. And there was also an omnipresent reminder of lifes unfairness and consequences.

His father, Jerome Allen, Sr., who left the home when his son was just ten years old, was lost to a paralyzing dope addiction.

Sports were more than a mere diversion for Allen during his younger days. They allowed him to formulate an early vision, as much of a long-shot and an unattainable goal that it may have seemed to be at the time.

He would be outside on the block, playing basketball on a milk crate that was attached to a pole all day long, said Janet. And hed always come home and tell me that he wanted to go to the NBA so he could buy me a house one day.

I just loved being outdoors and competing, said Allen. When I was growing up, whatever sport was in season, thats what we played. Football, basketball, baseball, we did it all. Sports gave me the chance to travel throughout the city. I didnt know that there were white people in Philadelphia until I started playing on teams and we went around playing other teams. In doing that, and seeing different things than what I saw in my own neighborhood, it opened my eyes up to so much more.

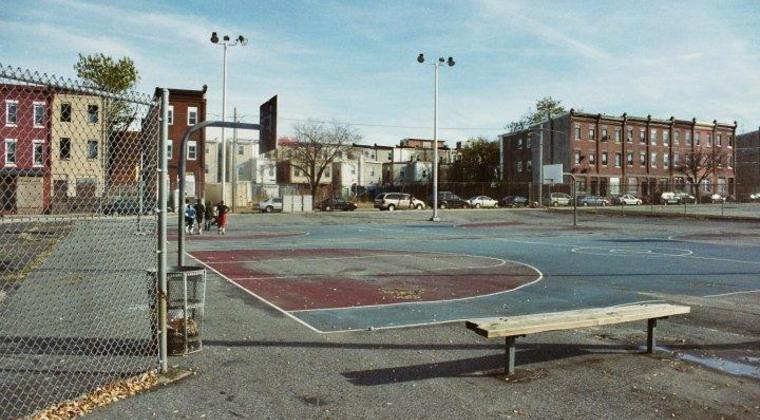

(16th and Susquehanna, North Philly. Photo Credit: courtsoftheworld.com)

His skills allowed him to sometimes compete up against older age groups. When he was 10, he played well in a game against a team of 12 to 14 year olds. He showed up at another recreation center a few days later to play in his normal age bracket, only to be rebuffed.

The guy who was running the league remembered me from when I played up against the older guys, said Allen. And he wouldnt let me play. He called me a ringer and said, No, no, no, that boy is too old. I was so excited to play that day. And when he told me I couldnt, I just started crying.

Hed walked a long distance to make it to the gym that day, but refused to take No for an answer. He scrounged up a bike, furiously pedaled back to his grandmothers house and burst through the door, out of breath, with tears streaming down his cheeks.

I busted in the house, crying, with snot in my nose, saying, Ma, ma, I need my birth certificate because this man is saying Im too old and he wont let me play, said Allen. She gave it to me, I jumped back on the bike, flew down there and made it back by halftime. Once that man saw that I was telling the truth, and how resolute I was, he wouldnt let me leave his side.

That man, Mel Kilgore, a coordinator with the citys Police Athletic League, became the first of many mentors and role models that took Allen under their wing. But young Pooh never had to search far for inspiration.

My mother got out of bed every day at 4:30 in the morning to catch public transportation for an hour-and-a-half commute to her job, cleaning hotel rooms said Allen. She pushed around a 200-pound cart every day that wreaked havoc on her back. Im sure there were many days when she was sick and didnt feel like going, but she went in every day.

My grandmother was a housekeeper, he continued. But the commitment they had to exhaust themselves to provide whatever their kids and grandkids needed, that sticks with me today. They gave us everything they had.

He was determined to carry that work ethic into his schoolwork and sports as well. But navigating the treacherous, tattered streets of North Philly was tricky. There were times where he made some bad choices and bumped his head, like the time he showed up for basketball practice inebriated at the age of 13, having sucked down a 40-ounce bottle of Coqui 900 malt liquor prior with some of the fellas.

The difference between possibly becoming a statistic, and one of Philadelphias favorite sons was a negligible one. But one chance, random encounter forever altered his lifes journey.

One afternoon, at the Gustine Recreation Center in the East Falls Projects, Allen was sitting in the Coordinators office doing his math homework. He knew that he wasnt allowed in there, but he wanted to be in a quiet space to complete his assignments before playing in his scheduled game that afternoon.

(Photo Credit: Penn Athletics)

The entire time that Id been to that recreation center, I had only done my homework in that office that one time, said Allen. He didnt allow any kids in his office because wed break into the cabinets and steal stuff like ping pong balls.

When the coordinator opened his door and saw Allen in there, he exploded.

Get the hell outta my office, the man screamed. I told yall kids to stay the hell outta here. What the hell you doin in here? Dont you have a game you should be getting ready for?

Yeah, but Im tryna hurry up and finish my math homework because I know that when I get home tonight, Im gonna be tired, Allen responded.

The coordinator was touched by the brief interaction and the sincerity of little Pooh wanting to do his homework. He assumed that he was a driven kid who, combined with his basketball skills, might have a chance to transcend the neighborhood and his familys circumstances. He proceeded to call a friend, James Flynt, whose son Bruiser Flynt, who is now the head basketball coach at Drexel University, attended Episcopal Academy.

Episcopal, a well-heeled, tony private school on the citys affluent main line, was a world removed from the environment that Allen was accustomed to. But James Flynt reached out to the school and asked them to take a chance on the kid.

The coordinator at the rec center changed my life with that one phone call, said Allen. That guy helped me get into Episcopal off of that one interaction. Had I not gone to Episcopal, Im not sure where my life would be right now, in terms of being able to provide my children with the foundation thats going to be able to sustain them for the rest of their lives. It changed the trajectory of my entire life.

While the frequently told story summons up the image of a young kid from one of Americas forgotten pockets of urban despair walking around with his school books, determined to chart a positive path for his life, Allens re-telling of the story is very much in line with his personality: insightful, reflective, humble, candid, authentic, intelligent, self-effacing and subtly funny.

I didnt merit that consideration, it really was a random circumstance, said Allen. Had he walked in his office the day before, he probably would have caught me stealing something. Its very scary to think about what I might have missed out on if that one thing hadnt happened. And I often ask myself, out of all the other kids, why was I chosen for this opportunity?

Allen entered Episcopal as a high school freshman. As he looked around at his classmates and processed their material wealth and possessions, he began to grow bitter.

Those kids were driving their own cars to school or they had nannies picking them up, said Allen. They wore nice clothes and when I went over to their homes, they had a bunch of food in the fridge. When youre exposed to certain things, it can affect you in different ways. I was bitter initially. But soon, it turned into a sense of, Ok, I gotta do X,Y and Z now, because this is how I want to live.

Nearly three months after he began attending Episcopal as a ninth grader, Janet Allen received an urgent letter from the Philadelphia public school system stating that her son had been truant for ten weeks. The letter was symbolic of what he was moving on from, but his struggles were far from over.

To Be Continued…

Part II – From Humble Beginnings: The Journey of Penn Coach Jerome Allen

Part III – From Humble Beginnings: The Journey of Penn Coach Jerome Allen

Series Intro: Ivy League Hoops, Ahead of the Curve in Coaching Diversity