There’s something special cooking in Atlanta and it ain’t mama’s fried peach pie.

The ingredients — by baseball’s recent standards — are rare, but the flavor’s nostalgically remarkable and it’s leaving a great taste in the mouths of the city’s African-American baseball fans.

By signing 25-year-old outfielder Justin Upton (three 3-years, $38 million), his 28-year-old brother, B.J. (five 5-years, $75 million), and fusing them with rising star Jason Heyward, the Braves reclaimed their status as MLB’s torchbearer for bad-ass black outfielders.

The formation of this multi-skilled clique has sparked a once-dormant optimism that Atlanta would recapture its lost black baseball audience.

“For me it’s such a relief to be able to see [the Upton brothers and Heyward] — I call them the Soul Patrol — in the outfield,” said former Braves outfielder Brian Jordan, who in ’00, along with Reggie Sanders and Andruw Jones, comprised the last Braves outfield prominent with shades of brown. “I haven’t seen anything like this since I was playing.”

Since Jordan’s prime years with the Braves (’89-’91), Atlanta’s black baseball superheroes have become almost non-existent.

Therefore, the presence of the “Soul Patrol” is also the Braves' first step in re-connecting with an African-American community that’s been feeling neglected due to a precipitous dip in black ballplayers. The number has declined since the ’90s when a slew of cats carried on the tradition of Hall of Fame inductee Hank Aaron who sparked the legacy in the ’60s.

These days, even Aaron, who continuously expresses his disappointment with the lack of black players in pro baseball, is encouraged that this potentially explosive Atlanta outfield will put baseball back on the radar of black athletes and families (albeit, still a distant second to the Falcons).

“I’m pleased, and I hear people from my area talking about how pleased that they are (with the Braves outfield),” Aaron said in a spring training interview. “So I’m hoping that (the fans) show their appreciation by coming to the ballpark.”

Chuck Johnson is one of a handful of black baseball writers and has covered MLB for over 18 years. Johnson developed his passion for baseball growing up in the ’60s, watching the dark knights of the diamond — Frank Robinson, Willie Mays, Hank Aaron, and the like — do things on a baseball field that even the X-Men couldn’t duplicate.

Without the unique substance and flair of these caliber players, baseball just isn’t the same quality game.

“Black athletes historically bring several things to the game of baseball,” Johnson added. “Speed and a style of play molded by the ‘black experience,’ which is rooted in the barnstorming Negro Leagues. Without black representation, baseball is missing a key ingredient to what made it America’s past time. It can’t be considered that without black ball players. We can’t possibly be seeing the best product.”

Black interest in baseball, overall, has been in steady decline. For some reason, the African-American community no longer sees it as an attractive athletic option.

The post-’‘90s Braves reflected this trend and were no longer a franchise that provided the black community with uniquely identifiable stars. The familiar faces that once tugged at the cultural heartstrings of Atlanta blacks, and contributed to their interest in Braves baseball, were fading.

Over time, baseball’s ethnic shift — highlighted by an influx of Latino players to fill the vacuum created by the exodus of black players — created further disconnect between the black community and Atlanta’s baseball scene.

“A lot of black folks were pissed with the Braves,” said Shadow League member Nubyjas Wilborn, born and bred in Atlanta. “When the outfield had black guys, naturally more blacks attended the game. We could relate to the players and supported the team. In recent years, blacks haven’t really been going to (Braves) games because the team is all white. They feel kind of like the team turned its back on us.”

In essence, with this dynamic outfield, the franchise is moving forward by returning to the basics.

“The direction the Braves want to go in is a throwback to the way we used to do it,” said Jordan. “They want to move in a direction of speed, power and defense. That’s what made Braves teams successful then. These three guys possess all the skills to do it.”

*****

It looks like Justin is on his way to a career year. He’s tied for the major-league lead in homers (6) and is smashing with a .353 batting average. B.J. and Heyward are off to slower starts, but if they all play to the back of their baseball cards, damage can be done.

The Uptons’ presence as veteran leaders with playoff experience is also valuable. The brothers will be expected to steady the line-up, so the talented crop of young-but-unpredictable Atlanta arms (Kris Medlen, Brandon Beachy, Mike Minor, Randall Delgado and Julio Teheran) can continue developing. If everything clicks, the Braves could be setting the stage for another ’90s-like string of success.

The Uptons were also brought in to provide the athleticism and all-around performance lacking in recent Braves teams. Just five games into this ’13 season, the Uptons ripped a pair of ninth-inning homers against the Cubs, to lift Atlanta to a dramatic 6-5 win.

It’s only April, but cable TV reports on the game suggested there was an October vibe swirling. The stands at Turner Field were packed. The heightened media portrayal of the game had a playoff tone.

Naysayers are doubtful that these three players can single-handedly enhance and further diversify the baseball culture in Atlanta. Some are resigned to the fact that only baseball fans watch baseball. And most black people aren’t turning from Love & Hip- Hop to watch a Braves game.

Well, Braves GM Frank Wren was looking for impact when he signed these cats. "We were in a transition phase with Chipper [Jones] retiring. So we had to kind of reestablish an identitiy for our ballclub…" he told the Washington Post. With the moves, they got the streets talking.

Adrian “AO” Williams is an Atlanta party promoter who also owns a hip-hop clothing store in nearby Augusta. Williams says that even non-baseball fans are “hyped” about Atlanta’s all-black outfield.

“Atlanta is trendy,” said Williams. “The Braves are hot right now. Some of us might not be baseball crazy, but we are feeling the Upton situation. When I go to the gym, dudes are talking about everything. Lately, it’s been the Braves. They’re playing Braves games at the little lounges and what not. I might have to start playing the games on screens at the store.”

Jordan, who hosts a radio show on 1100 AM The Game in Atlanta and works with Fox Sports South, has a good grasp on the temperament of Atlanta sports fans. He supports the early notion that fanfare surrounding The Uptons’ arrival shows that baseball has a pulse in black Atlanta. “People that haven’t gone to Braves games are going, and nothing’s stopping them,” Jordan boasted. “There was a huge weekend here with the Final Four festivities and even that didn’t affect the Braves crowd, at all.”

So far, Jordan isn’t lying. Although it’s just an early sample, the Braves are averaging 35,296 fans at Turner Field through six games, compared to last season’s average of 29, 878. The attendance numbers could drop, stabilize or decrease depending on the Braves’ success, but it’s clear that the Uptons’ arrival has peaked early interest.

“That’s how Atlanta fans are,” added Wilborn, a frequent co-host on Jordan’s show. “There are more black people in the stands at pro sporting events in Atlanta than any other major market. If you give us players we can relate to…and they win…we’ll support the team. I mean, we supported the Thrashers (NHL) hockey team just because they had five black players.”

Sustained success will determine just how realistic and effective Atlanta’s outfield is at healing the city’s fractured baseball culture; but, for a celebrity-popping, socially -progressive enclave like ATL, embracing three young, black, rich, ball-bashing pros shouldn’t be a problem.

*****

Black outfielders, such as Ron Gant, Lonnie Smith, Gary Sheffield, and Jheehri-Curl-dripping Otis Nixon, were staples of the wicked Braves teams of the ’‘90s that won 14 straight Division titles and a World Series. Then, as baseball’s African-American participation dipped, all-black outfields disappeared.

The highest percentage of African-American players in the MLB was 27 percent in 1975, based on a 2007 report by ESPN. By 1995, it was down to 19 percent. As of ’12, the numbers have tumbled to about 8 percent, less than half the 17.25 percent in 1959 when the Boston Red Sox became the last team to integrate their roster.

The causes of this cultural transformation are constantly debated , but what better an outfield to turn the tide. In society, people tend to support those who share common social-economic or ethnic backgrounds; it’s called tribalism. When brothers gain high notoriety in a sport where they have low representation, it causes a stir and other African-Americans take notice.

The Uptons are evenly matched as players and are the only brothers in MLB history to have seasons of 20 swipes and 20 bombs. B.J., a former Tampa Bay Rays centerfielder, is a human highlight-film on D. He strikes out a bit much but can go on five-tool tears. Justin, a former Arizona Diamondback, has a bit more power., He also Ks over 100 times a year, as well,, but hits for higher average.

Both broke into The Bigs at age 19 and are just entering their baseball primes. Heyward is the baby of the bunch. He’s been compared to Aaron ever since his lightning-quick bat caught major wreck as a rookie in ’10. Aaron’s high hopes for the Braves outfield lie most heavily with Heyward — a Gold-Glover who still needs to find some consistency at the plate.

“We (African-American ballplayers) still have a ways to go,” Aaron told thegrio.com in ’10 . “Yes, I’m somewhat disappointed in the lack of African-Americans (in baseball, but) having Jason Heyward is going to prove that given the opportunity, we can do the job as well as anyone else.”

These outfielders seem to have the weight of the world on their shoulders. Heyward welcomes the opportunity to open up some eyes, but he downplays the trio’s ability to put a major dent in this black-baseball slide.

“I can be a positive role model for a lot of people,” says Heyward in an April ESPN interview, “but no matter what I do or how much love I have for the game, I can’t choose the sport for anybody else.”

Heyward’s reluctance to be burdened with things that he can’t immediately change is understandable. It’s also impractical. Under baseball’s current landscape, The Uptons and Heyward are more than just some brothers out there balling. They represent the lifeline of baseball’s rich history of African-American stars.

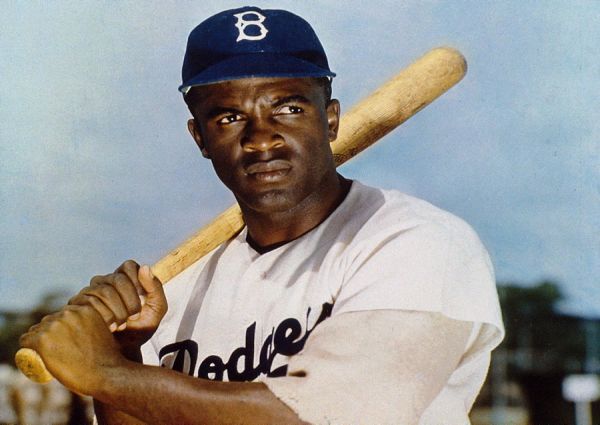

Nobody’s asking them to alter the world. This isn’t MLB’s first all-black outfield. The 1951 San Francisco Giants set it off with Willie Mays, Monte Irvin and Hank Thompson. The ’83 Oakland A’s had Rickey Henderson, Dwayne Murphy and Mike Davis.

But people, like Braves first base coach Terry Pendleton, think they can be game-changers of sorts.

“You could possibly have three 30-30 guys in the outfield,” said Pendleton, also a former star third baseman on those ’90s Braves teams, winning the National League MVP in ’91. “That would be the first time ever. Just thinking about that is crazy.”

Once the Braves outfield catches wreck on the field, the profound cultural marketing appeal will naturally follow.

In addition to a rare combination of skills, undeniable swag and confidence, these cats are also considered fashion-savvy, as witnessed by several features in Complex magazine. Just look at the B-boy stance Justin is in on their ESPN Magazine cover. If you’re familiar with their come-up, you know that the Upton brothers were always superior talents with a special destiny. Finding black ballplayers on any MLB roster is a challenge these days. The fact that one modest family from Chesapeake, Va. could produce two stars is epic.

The “Three Amibros” may not rival Jackie Robinson’s seismic effect on black culture but the triumvirate is living proof that there is a mound of untapped talent rotting away in America’s black communities. If African-Americans are ever going to regain their passion for baseball, the new revolution starts with something as familiar as mama’s hot fried peach pie: Atlanta’s rich, black heritage and engaging all-black outfield.