This time last year, I fought off nausea as I sat in Amway Center and watched the NBA Slam Dunk Contest turn into Disney on Ice. Kevin Hart was fluttering around the court acting like Kel from “Keenan and Kel”; Chase Budinger was cornily (new word) channeling Woody Harrelson; Derrick Williams entered the arena riding on the back of a motorcycle driven by a mascot; and, of course, Paul George decided it was dope to dress up like Meteor Man for one of his dunks. Whereas the dunk contest is usually full of baritone rumblings and “ooooooohhhhhhhs,” the Orlando joint was soundtracked by high-pitched shrieks of pre-teens. You could have put the court on wheels and made it part of Disney’s SpectroMagic parade.

The next night, at dinner, Shadow League head honcho Keith Clinkscales and I wondered aloud if the NBA shouldn’t just shutter the event, give it a seat for a few years, recalibrate. My Pops was always preaching to me about the socio-cultural significance of “the dunk.” He says it’s a shining example of black art and black power, a symphony of aggression and creativity. He would get irate when the rest of the country grew bored with the dunk contest. He thought it was, at best unwarrantedly dismissive or, at worst, nefarious. So even during the contest’s down-years, I try not to get bamboozled into the wholesale diminishing its relevance and entertainment value.

But these last few years of shenanigans make it hard. This past weekend’s contest reinforced the necessity to kill this charade.

We saw more missed dunks than makes, nothing was spectacular and none of the participants carried themselves with the charisma needed to command an audience. If you didn’t know who James White is, coming into the contest, his limp-armed, sullen, unassuming performance in Houston definitely didn’t leave an impression.

There’s a growing consensus that the NBA needs to chill on the dunk contest, unless, miraculously, Russell Westbrook, Blake Griffin, a healthy Derrick Rose, LeBron James and Rudy Gay want to go at it, next year. And that won’t happen. We’ve tried to guilt and shove starts into the competition over the years and, for a variety of reasons (fear of injury, fear of failure), it doesn’t work.

What’s comforting, however, is the knowledge that the dunk contest will inevitably return to glory one of these years in the future. That’s how it goes with the dunk contest. Its history is one of rises, falls, spikes, plateaus and such.

**********

On the real, the dunk contest was really started because Dr. J played basketball. Julius Erving’s legend was mammoth, based on his exploits at Rucker Park, in college in Massachusetts and his early ABA days. The ABA set off the first dunk contest in Denver. It featured David Thompson, Artis Gilmore, George Gervin, Larry Kenon and the Doctor.

Doc still had the cold-blooded Afro. He took off from the free-throw line. His legend grew.

But the rest of the contest was somewhat pedestrian. The pageantry wasn’t there, yet. Gilmore dunked two balls at once and then walked back to the bench the way your co-worker walks back to his desk after grabbing some coffee from the break room. Swag was nonexistent, but the sheer novelty of the competition was enough to capture the imagination.

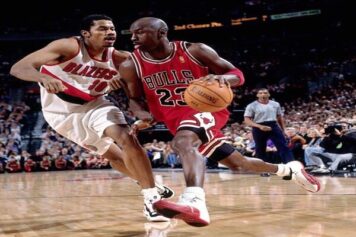

It took the NBA eight years to follow up. In 1984, back in Denver, they dragged out an old Dr. J, along with Larry Nance and some others, for its inaugural contest. Nance won. The Doctor wondered why he was even invited. 1985, it got a little more serious. Dominique Wilkins was tomahawking on lames; Darrell “Dr. Dunkenstein” Griffith was getting his Sherman Hemsley on; Terence Stansbury hit you with a nasty “statue of liberty” joint and—get this—there was also a young, seemingly disinterred, Michael Jeffrey Jordan involved. He was a rookie. He actually rocked all his Nike gear for his first few dunks then abruptly appeared in his jersey (probably got a mob-boss nudge from The Commish). This wasn’t the dunk-contest Jordan of the next few years—this was a kid who hadn’t yet understood the marketing/branding power the dunk contest could provide.

At this point, the contest was still on steep upward trajectory. Spud Webb took it to a whole other level in 1986. The 5’6 runt (by NBA standards) stunted on ’Nique and all the other participants (MJ was injured)—his performance became a zeitgeist thing. And then MJ took it to the stratosphere for the next two years, peaking with his controversial duel with ’Nique at the 1988 All-Star weekend in Chicago.

It dipped and plateaued after that. Kenny “Skywalker” had some legitimate winners, but how do you follow up MJ? By the time ’Nique won again, in 1990, the contest was starting to lose its luster. Dee Brown’s 1991 win was a bit of a tipping point. He leveraged his Reebok pumps and no-look gimmick for a solid albeit jester-ish win. The train came all the way off its tracks the following year when—amid one of the great power dunking displays in history by Larry Johnson—Cedric Ceballos clowned his way to win with his weak “blindfold” dunk. It was a dunk meant to serve as an interlude at a Siegfried & Roy show in Vegas.

The contest wouldn’t stay in the playpen doldrums for too long, though. The next two winners—Harold “Baby Jordan” Miner and Isaiah “High As A Kite” Rider—turned in two of the contest’s best performances (not to mention Shawn Kemp and Robert Pack in losing efforts). Then a white man (Brent Barry) won the contest in 1996 and had us rethinking the competition and just life, in general. By the time Kobe won the ’97 contest with mostly retread dunks against no-names, everyone agreed: let’s shut this thing down.

It’s not that the NBA swapped in a more compelling All-Star Saturday event, it’s just that the dunk contest had degenerated into an event that only attracted derision.

The dunk contest was resurrected for one reason and one reason only—because Vince Carter was playing basketball and, throughout his early career, put forth a collection of in-game dunks more incredible than anything we’d seen before. There was a groundswell of fans calling for him to show out in the contest, so the NBA brought it back in Oakland.

And this happened:

All things considered, that was the high-mark for the dunk contest. You had the greatest dunker alive (maybe to ever live) going berserk while two other cats—Steve Francis and Tracy McGrady—turn in all-time performances that still weren’t able to do anything but wilt from the VC-heat.

Between Carter’s win and the contest’s third peak (Dwight Howard’s 2008 win over Nate Robinson) we watched ultra-athletic cats like Josh Smith and Jason Richardson put on solid shows, but nothing that crossed over and became a cultural phenomenon.

That’s how this goes. If it weren’t for Dwight donning a Superman cape or Blake Griffin’s coronation, the American yawns directed at the dunk contest would have probably turned to ZZZZs a few seasons ago.

But Clockwork Orange-ing us with the kiddie fare of these past two contests is motivation to give the dunk contest some ambient, so it can take a nice long nap, recharge and come back when some athletes and personalities warrant it. In the meantime, we can watch college basketball warm-ups to get our missed-dunks fix and the “Backyardigans” when we need to entertain grade-schoolers.

Peace, dunk contest. We’ll catch you on the rebound.