To get an essence of what Willie Howard Mays Jr. contributed to the sport of baseball would truly take a lifetime.

That being said, I’m up for the task of giving you and all of our readers a respectable snapshot.

When you see a Ken Griffey Jr. or a Byron Buxton glide effortlessly in center field to snare down a line drive in the gap, you’re seeing Willie Mays.

When you see a Kenny Lofton or a Mookie Betts go from first to third at warp speed, you’re seeing Willie Mays.

When you saw Nate Colbert, or a Mike Cameron, or a Mark Whiten put on an awesome display of power in a doubleheader, you saw Willie Mays.

Willie Mays Was The Quintessential Five-Tool Player

When you hear the term “a five-tool player,” you’re talking about Willie Mays.

Moses Fleetwood Walker and Jackie Robinson paved the way for guys like Aaron, Robinson, Gibson, and others.

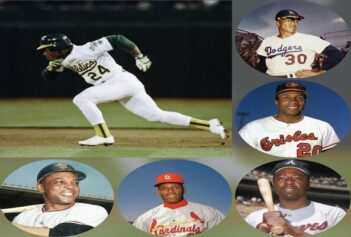

They all had their own unique styles and approaches to the game. However, No. 24 brought a whole different style, swagger, and flavor to the game.

Many of us who are baseball fans of a certain age are also lovers of jazz music. Let’s not forget the the improvisational nature of the genre whether it’s a Charlie Parker, a Quincy Jones, or a Wynton Marsalis.

When I hear the genius riffs of these great musicians, I think of baseball and most importantly, The Say Hey Kid, Mr. Mays.

The basket catch. The waggling of the bat before a pitch. The commanding swagger in center field.

All of those things set Willie Mays apart from his contemporaries.This is way beyond the 24 All-Star Game selections, the 12 Gold Gloves, the two MVP awards, the 3,293 hits, and 660 homers.

The Alabama native passed away Tuesday afternoon at the age of 93. It comes days before the San Francisco Giants are set to face off against the St. Louis Cardinals at Rickwood Field in Birmingham, Alabama, in a game honoring Mays and the Negro Leagues.

It was announced on Monday that Mays would not be able to attend. Mays, who was born on May 6, 1931, began his professional career at the age of 17 in 1948 with the Birmingham Black Barons, helping the team to the Negro League World Series that season.

“My father has passed away peacefully and among loved ones,” Michael Mays said in a statement released by the Giants. “I want to thank you all from the bottom of my broken heart for the unwavering love you have shown him over the years. You have been his life’s blood.”

As a young writer in the late ’90s, I was blessed to be able to interview Mr. Mays for my hometown newspaper. He and fellow Hall of Famer Mickey Mantle were only a few years removed from being reinstated by then commissioner Peter Ueberroth because of their “association” with a casino in Atlantic City.

Willie Mays’ Time With Giants Wasn’t All Sunshine and Roses

Yes, there was a time that baseball and casinos were not mentioned in the same breath. But that’s another story for another day. Mays stated one of the first entities that reached out to him was his former team, the San Francisco Giants.

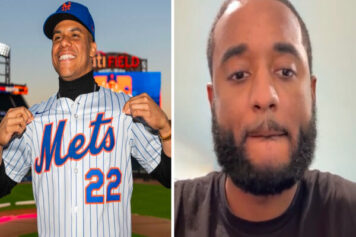

Willie’s relationship with the franchise had become estranged over the years due to the fallout of his 1972 trade to the New York Mets. “Mr. Stoneham told me he would never trade me and I felt very betrayed”, Mays said.

The rift between Mays and the Giants was so deep that Mays’ displayed jersey at the Hall of Fame was originally a New York Mets No. 24 instead of a San Francisco Giants No. 24. When team owner Bob Lurie privately reached out to Mays following his reinstatement, the Giants named him a special assistant to the president and general manager.

By 1993, Mays, along with former teammates Willie McCovey and Orlando Cepeda signed a lifetime contract with the team and helped to muster public enthusiasm for building the Giants’ new stadium, Pac Bell Park (now Oracle Park).

Over the years, he’s served as an ambassador for the Giants and baseball in general. All told, in a career that spanned 20-plus years (1951-73) — most of them with his beloved Giants – ranks sixth all time in home runs (660), seventh in runs scored (2,068), 12th in RBI, (1,909) and 13th in hits (3,293).

In a statement from the MLBPA, executive director Tony Clark said Mays “played the game with an earnestness, a joy and a perpetual smile that resonated with fans everywhere. He will be remembered for his integrity, his commitment to excellence and a level of greatness that spanned generations,” Clark said.

Center fielder Willie Mays of the New York Mets leaps high at the wall to rob Darrell Evans of the Atlanta Braves of a home run in the eight inning during a game at Shea Stadium on July 8, 1973 in Flushing, Queens, New York. The Braves won 4-2. (Photo by Louis Requena/MLB via Getty Images)

The legacy of Willie Mays will live forever within the current crop of African-American players of today and the future. To many, he remains The GOAT.