Tony Harrison grew up in the streets of Detroit, one of Americas murder capitals, where poverty was prevalent, opportunity was minimal and fighting was a way of life.

Thats the main reason why Harrison (22-1,18 KOs) is booming with confidence about his middleweight fight on Saturday, March 5 against Fernando Guerrero (28-3), considered one of the top 160-pound fighters on the globe. The two championship hopefuls square off in a critical showdown on the undercard of Showtimes Julian “J-Rock Williams vs. Marcello Matano main event at Sands Bethlehem Event Center in Pennsylvania.

Tony Harrison:I got the heart. The speed. I possess it all. I got the height and the confidence and most of all I just think I came up harder than a lot of these middleweights. Fighting wasnt a choice for me and its hard to beat somebody who grew up in that environment. It was either fight or be a victim of the crime rate. There werent many choices for me.

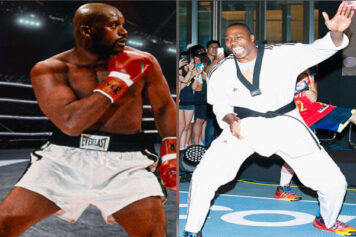

The 25-year-old rising middleweight from the D embraces struggle with an unwavering confidence and hand-to-hand combat is an art form that runs thick through his veins. Harrisons dad, Ali Salaam, was a welterweight prizefighter. His grandpa Henry Hanks (born Joseph Harrison before converting to Islam in 1971) was considered one of the hardest punchers in boxing during a 19-year career in which he faced the best fighters of his era, including five International Boxing Hall of Famers.

Pedigree

A cat like Harrison has been bred to literally roll with the punches, but it wasnt the men in his family who steered him in the direction of boxing. As a child it was his mom, who thought he should go to the gym and work off some of that youthful aggression. His father and grandfathers boxing prowess would eventually emerge as the driving force behind his fighting ambitions, but only after the seed was planted by his mom.

T. Harrison: “As a kid you just go along with the times. When I was a little kid I never worried about what my history is. I was just running around outside, playing football and I had to fight..EVERYDAY. Fights came along often for me. Boxing wasnt on my mind. Eventually my mom felt like instead of me fighting in the streets all day, its time to get me in the gym. From there, they started to break down the history of my family to me and as I got older I started to understand that this may be a gift for me. This is a part of my blood. Being in the gym and practicing the craft inspired me to find out how good my granddaddy really was as a boxer. I found out and I wish he was alive to this day to see my improvement.”

Harrison will be attempting to build on that improvement against Guerrero on Saturday night. Its an obstacle, another fight, he has to conquer or risk falling out of championship contention.

T. Harrison: “This is a step up fight man. If I cant beat Fernando then I been doing this shit my whole life for nothing. I should be able to beat whoever it is they put in front of me.”

Harrisons career was taking off like a rocket launcher as he won his first 20 professional fights and became known as one of boxings knockout kings. Some even called him a “Sugar Ray Leonard-type.” However, boxing is as unpredictable as a late night stroll through Detroits Southwest Side. A loss is always lurking and if you get caught slipping, a promising career can become a quick wrap.

Harrison was beaten by Willie Nelson in July of 2015. Harrison, who often speaks of himself in the third person, says it was a minor setback and part of a growth process that will strengthen him as he ascends to the middleweight championship. He quickly redeemed himself against Cecil McCalla a few months later.

T. Harrison: “The 22-1 record…that one loss isnt really a loss for Tony Harrison. Its one lesson. Ive learned from it and right now I just want to get back up on that pedestal so I can get that rematch and I have to go through Fernando to do it. Hes a championship contender so hopefully the great performance I put on brings me a rematch or even something better.”

The Shadow League: So what did you learn from that …lesson?

T. Harrison: “You cant knock everybody out, especially that late in the fight when you have it won…just win. Dont make adjustments during the fight when everything you were doing was working for you. As far as training goes, I did everything right. Next time I would do the exact same thing but just stick to the game plan until the fight is won. Not only did I learn, but my corner learned as well. The talent is still there and Im still hungry and I’m still from Detroit.”

Emanuel Steward

Speaking of Detroit and unexpected losses, the late great trainer Emanuel Steward, who passed away in 2012, guided Harrison through his early years. Steward was the godfather of Detroit boxing and responsible in some way for shaping the success of every boxer to come out of the urban rumble jungle since he and his protege, Thomas “The Hitman” Hearns, laid it down for Detroit out of the fabled Kronk Gym back in the day.

Harrison tells TSL that Stewards passing was a huge loss, but for reasons beyond Stewards incomparable boxing intellect.

T. Harrison: “Emanuel was my man…my dog and thats why we clicked so good. He wasnt just business and calling me saying, Tony we have a fight here or We have a fight there. It was more of a friendship. We went everywhere together. Emanuel stayed right around the corner from and we shared many experiences. Whether it was to go pick up a pie around the corner from the pie lady or sharing detergent. Or flying across the country to meet him at an event at the drop of a dime at 18-19 years old, just because he asked me to.”

“Besides what he accomplished in boxing, I miss him as a friend more than anything and the times we shared together. It was a blessing to have somebody of wealth and experience who understood what we were going through and the struggles we had to overcome because he was from there. And I was lucky to have that wisdom around me to teach me things like tipping the waiter and tipping the stewardess and pulling up your pants up and wearing a suit every now and then. Those are elements of life I would not have learned if he wasnt my friend.”

The Big Picture

Harrison could use Stewards Hall of Fame tutelage against a true boxing warrior in the 29-year-old southpaw Guerrero, who fought Peter Quillen for the WBO world middleweight title in 2013. However, he’s in good hands with his father and brother training him.

Thats why even if Harrison takes an L and has to go back to the drawing board, he says it wont be as life-altering, psychologically-taxing and painful as losing his family at 16.

T. Harrison: To be honest I think getting kicked out of my house and my family splitting up was the toughest thing that ever happened to me. My parents going one place and me going elsewhere. Not because we lost everything, but the bond I had with my parents was so tight that once I got on my own, I lost a little connection to how we used to do things.

We used to eat together and talk at the dinner table. That was lost when I was in high school because we had to split up to survive and I went with my cousin, who was only 23 with a wife and kids when he took me in… so he gave me more leeway than my parents did. The hardest part was from that point on, I hustled on my own. Also my brother was going to college and he was my best friend. I was the last kid in the household. I was really by myself.

Now that Im older I understand the decision they had to make, but it happened in my prime years and it changed how I looked at life and how I felt about myself. I was running the streets. My cousin was morally strict, but he let me live my life as a young man.

Harrison has a keen understanding of the plight facing black urban youth in America. He detests the economic and systematic ruin that plagues his city. He also remembers how Steward embraced him at a critical and trying juncture in his life, and thats why Harrison spends his free time mentoring Detroits youth as a football coach.

He and his cousin, San Diego Chargers legend Antonio Gates, started The Michigan Bulldogs, an American Youth Football team for kids from the second to ninth grades.

Harrison wants to share the jewels and offer inner-city Detroit kids a glimmer of hope and self-worth through football. Hes helping these kids get an early start on becoming contributing members of a society that has left them in the dust to rot in a fallen city, gutted and demoralized by capitalistic greed and corporate outsourcing. Early development of a child’s thirst for success is critical, especially for kids from underserved communities.

T. Harrison: Its like my grandfather always told me, ‘As a fighter, if you stay ready, you ain’t gotta get ready.'”