This is the second installment of our series entitled "Ivy League Hoops: Ahead Of The Curve In Coaching Diversity."

Next week’s feature is Yale’s James Jones.

PART I

If you think that Tommy Amaker is merely a coach, you’re mistaken. He does coach basketball. But to assume that the job title is an apt description of what he does, and who he is, would be like saying that Harvard University, the institution where he plies his craft, is merely another school.

In reality, Amaker is a builder of things: An architect who specializes in renewal and revitalization. He begins each task with a vision, whether it’s an hourly, daily, weekly or long-term undertaking, buffeted by a blueprint and an inner passion.

Since being named Harvard’s head coach in April of 2007, he has annually raised the bar, setting new criterions of success at the school that had not appeared in the NCAA Tournament since 1946, back when Harry Truman was the President of the United States. And when the forerunner to what is now the NBA, the Basketball Association of America, was initially founded.

Amaker has established the Crimson as a dominant force within the Ivy League over the last seven years while revitalizing and reinventing the program into one with a national presence. Harvard now genuinely competes for a small subset of the country’s top recruits, players with exemplary scholastic backgrounds who, not long ago, would have solely considered elite academic schools in power conferences like Duke, Vanderbilt, Northwestern and Stanford.

His enthusiasm and fervor is impossible to ascertain by simply observing his cerebral ruminations, mild countenance, engaging smile, sartorial splendor and the magnetic way that his measured, melodic words conspire with his calm, regal bearing in a fashion that inevitably makes one feel welcome, important and assured in his presence.

To fully understand the depth and zeal that simmers beneath his composed façade, you have to reach back in time to connect with the young boy who grew up in the Washington, D.C. suburb of Falls Church, Virginia in the early 1970’s.

THE INCUBATORS

Order. Discipline. Planning. Preparedness. Effort. Those were the qualities that were naturally imbued in him as the son of a military man and a mother who was a dedicated schoolteacher.

“Education was very important, following orders were very important, and that has served me well in the latter years,” said Amaker.

He spent a lot of time with his grandparents, who lived near the James Lee Community Center in Falls Church, Virginia, an oasis that would formulate the bulk of his childhood dreams. He practiced so much on a portable hoop at their house that the patch of grass surrounding it would remain bald for over a decade.

“Basketball and tennis was what I gravitated towards,” said Amaker. “My idol growing up was John Lucas, the great tennis and basketball All-American at the University of Maryland. That was the beginning for me.”

He was drawn to the playgrounds and area gyms, watching and studying the games of older relatives and guys from the neighborhood that he admired. As much as he enjoyed playing tennis though, the team aspect and camaraderie of hoops sucked him in like quicksand.

He was a natural facilitator from the very beginning. Amaker invested his time not only practicing the game, but thinking it as well, through all of its various nuance and permutations. Honing his dribbling, vision and passing ability, along with an advanced understanding of the game’s unique rhythms, spacing and geometry, enabled him to excel at an early age, despite his slim build and diminutive stature, in an area that is synonymous with producing elite basketball talent.

“As a smaller guy, you have to find ways to make your mark,” said Amaker. “You have to have some toughness about you. You’re going to get knocked around. You’re going to get picked on. But those things can serve you well as you keep moving forward and learn from it.”

His mother however, was not as philosophical or understanding. At W.T. Woodson High School, he earned a starting position on the varsity squad as a 5-foot-7, 108-pound freshman, despite the bottom of his jersey dangling out of his cookie-cutter shorts, tickling his thighs and bony knees.

Alma Amaker, who custom-tailored her son’s jersey, shortening and hemming it at the shoulders so that referees could see his number 10, would often attend practices. She’d sit in the coach’s office, grading papers, waiting for Tommy to finish.

Once, when her son got knocked to the ground, she angrily attempted to walk onto the court. She pleaded with him, asking that he refrain from attacking the paint against bigger and stronger players, only to be calmly rebuked with, “Now Mom, if you can’t take it, you can’t come to the game.”

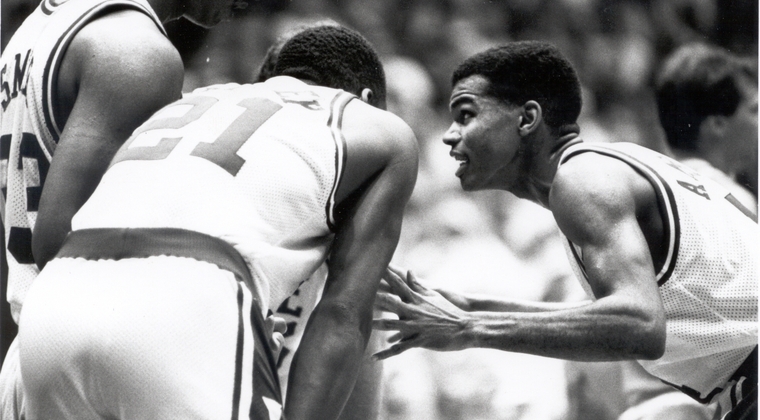

(Photo Credit: Duke Sports Information)

After one summer league game against the famed DeMatha High School program, where he scored 36 points and dished out 12 assists, Red Auerbach, the legendary coach and executive of the Boston Celtics, called him the best high school point guard he’d seen in ten years.

“The summer league was a big part of the growth of a lot of good players,” said Amaker. “That has changed somewhat now with AAU summer basketball. But back then, you had guys like Red Auerbach who would go to those games. To have that said about me as a player still blows me away, coming from the great Red Auerbach.”

Considered one of the best pure point guards ever to play in Northern Virginia, Amaker’s approach to the game was an unselfish one. The team and winning came first, above personal statistics and accolades. He took great pride in playing fly-paper defense and elevating the play of his teammates. He was also ambidextrous, so there was no weak hand to neutralize off the dribble. And despite being a decent shooter, he preferred to create scoring opportunities for others.

Recruiting mail began arriving that freshman year. By the time he was an upperclassman, all of the big time college basketball programs were fawning over him. But serendipity intervened when a young coach named Mike Krzyzewski popped into D.C.’s Jelleff Summer League to observe his top recruiting target: A quicksilver, tough, explosive and sinewy scoring machine at Mackin High School named Johnny Dawkins.

When asked by a local coach if he came to see Dawkins, Krzyzewski nodded. When told that he might want to stick around to see another kid who was just as good, Coach K had his doubts. But he stayed longer than he’d originally planned, just in case. It turned out to be a fortuitous decision that forever altered the trajectory of Duke University basketball.

Coach K was so enamored with what he saw that night, that he approached Alma Amaker and gushed, “Your son is going to look great in Duke blue.”

SETTING THE STANDARD AT DUKE

Duke was far from a powerhouse in those days. Krzyzewski was viewed as an unproven coach who had a losing record during his previous stint as the head coach of Army. He was coming off of back-to-back losing seasons at Duke and, as implausible as it seems now, was on the proverbial hot seat.

Tommy averaged almost 18 points, eight assists and four steals per game over his four-year high school career. When Dawkins, who grew up playing with and against him in the incubator of D.C.’s recreation and summer leagues, chose to attend Duke, Amaker followed suit a year later after being named a prestigious Parade and McDonald’s All-American.

“I believed in Coach Krzyzewski and his vision,” said Amaker. “Here comes this young coach who was trying to build something at Duke and he was going through some tough stages there. But Coach K was the one who saw the vision of Johnny Dawkins and I being a tremendous college backcourt together. He saw that, and it just blew me away how much I fell in love with the guy.”

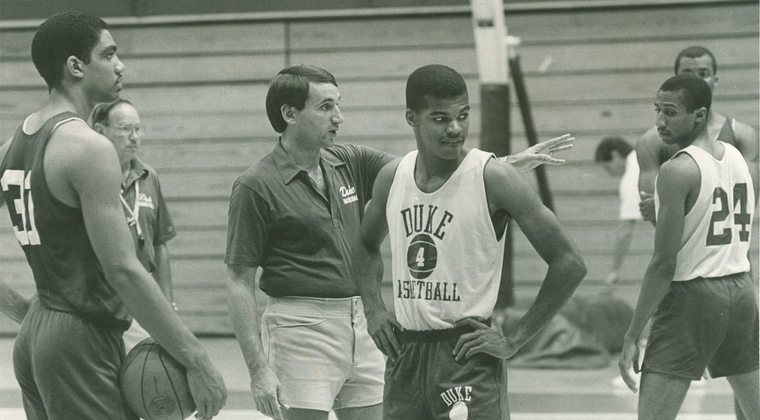

(Photo Credit: Duke Sports Information)

Amaker was delighted at the prospect of establishing something special as a college player. He found the idea of building the foundation of a program and helping it grow more attractive than the other schools that dangled their previous Final Fours and National Championships at him as recruiting bait.

“It was an amazing experience, looking back at those moments where Duke and Georgia Tech were fighting to be relevant, trying to become a factor,” said Amaker. “To have a chance to be on the ground floor of something, to be a part of something as it grows, to take ownership in it like that, it was almost like, ‘Why wouldn’t you do that?’ It was the right fit for me, one of the best decisions, if not the best decision that I ever made.”

Amaker was the first point guard that Krzyzewski recruited as Duke’s coach. He started from day one, and along with Johnny Dawkins, formed one of the best backcourts in the history of college basketball. Duke won seven games in a row to open his freshman year as the team secured Coach K’s first ever NCAA Tournament bid.

One writer, commenting about Amaker’s defensive prowess, said that he could steal the contact lens from someone’s eye without being noticed. And despite his leadership, composure, passing and elite defensive skills on the court, his impact was equally impressive away from it.

One night during his freshman year, teammates Dawkins, Mark Alarie, Jay Bilas and David Henderson knocked on the door of his dormitory room, hoping that Tommy would join them as they were heading to an on-campus party.

Amaker opened the door, attired in his bathrobe and underwear, with a toothbrush in his mouth. He coolly glanced at his watch, removed the toothbrush, looked at his older teammates and said, “If it ain’t done before 11 o’clock, it ain’t getting done,” before closing the door.

“I couldn’t function if I didn’t get my rest,” said Amaker, smiling wide and chuckling at the memory. “That was my saying, and the guys used to laugh at me, but that didn’t bother me. By 11:00 or 11:30 PM, it was time for me to shut it down.”

During his junior year in 1986, Duke went 37-3, winning 21 consecutive games, and advanced to the NCAA title game, losing a thriller, 72-69, to Louisville. It was the start of an amazing run that would later firmly establish Coach K as one of the greatest team coaches in the history of sports.

“In 1986, we had an amazing year,” said Amaker. “If you ask Coach K about some of his biggest regrets, he’ll probably mention the ’86 team not winning it all, because we thought we had the nucleus of a true team, in terms of how we played with and off of each other. Being a part of that group was really special. I don’t know if I’ll ever be a part of a group like that in my life.”

Over that summer, he was named to the Team USA national squad that captured the gold medal in the World Championships in Spain. Playing under Arizona’s Hall of Fame coach Lute Olson, his teammates included Steve Kerr, Sean Elliot, Kenny Smith, Muggsy Bogues and David Robinson.

(Photo Credit: USA Basketball)

“We were the last all-college team to win a gold medal in the World Championships or the Olympics for our country,” said Amaker. “That was a once in a lifetime opportunity and for us to win, it was an amazing moment for me.”

With the graduation of Dawkins, Bilas, Alarie and the remaining core of the team that re-established Duke as a national power, little was expected during Amaker’s senior season, which was the year that the NCAA instituted the three-point shot.

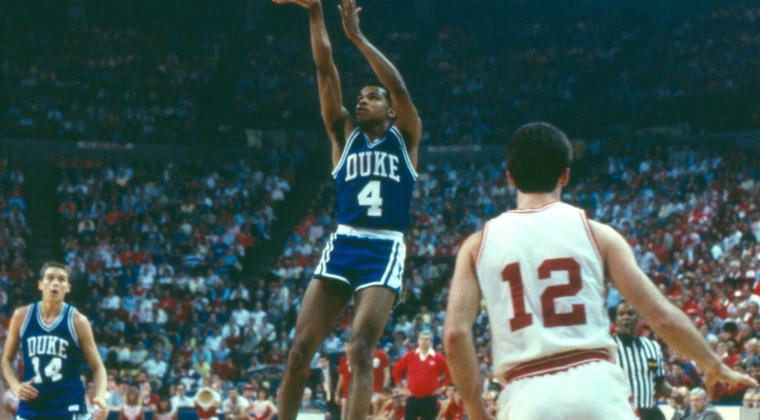

He wound up leading the inexperienced team to the Sweet 16. Against Indiana, the team that would go on to win the championship that year, in the regional final, he gave the Hoosiers’ dynamic backcourt of Keith Smart and Steve Alford 23 points in his collegiate finale.

He walked away from Duke owning every significant Blue Devils steals and assist record, having played in the golden era of the ACC, competing against the likes of Michael Jordan, Muggsy Bogues, Len Bias, Spud Webb and Mark Price.

(Photo Credit: Duke Sports Information)

He set the school’s absurd standard of excellence in terms of diligence, leadership, defensive tenacity and floor generalship against which every other incoming point guard, from Bobby Hurley to Jason Williams to Kyrie Irving, would be measured.

“The ACC had some great players, some great teams and the guards in that conference were outstanding,” said Amaker. “My freshman year in high school was when the Big East started, so the ACC was as big as it could get.”

NEXT STEPS

At 6-feet and a slight 150 pounds, he was considered a long shot to make it in the NBA. Drafted in the third round by the Seattle Supersonics, he was cut during training camp. Unfortunately, there were two more talented guards ahead of him, Sam Vincent and Nate McMillan, which left no room for him on the roster.

Still, he was let go with reservations by the Sonics coaching staff.

“The Tommy Amaker’s stay with you,” Seattle’s head coach Bernie Bickerstaff told the Boston Globe’s Jackie MacMullan in 2007. “He was a guy I was pulling for. But when it came down to it, all I could do was to look him in the eye and tell him the deal. Tommy handled it with professionalism. He always seemed to have things in perspective. He struck me as a person who could surmount any amount of adversity.”

With his playing days now behind him, he decided to return to Duke and earn his M.B.A. from the Fuqua School of Business.

But Krzyzewski had other ideas. He asked Amaker to work with the team as a graduate assistant during his first year in the M.B.A. program. When a full-time assistant’s position opened the next year, Coach K approached him with an offer that would significantly alter his life trajectory.

“Coach wanted to know if I wanted to leave the M.B.A. program, become a full-time basketball coach and look at this as another opportunity in my journey of life,” said Amaker. “I was blown away and very proud that he would think of me in that way, that he would have enough trust and belief in me that I could have some value to him in that capacity.”

Amaker apprenticed under Krzyzewski for nine years, during which Duke made five consecutive Final Four appearances and won back-to-back NCAA Championships, becoming the first team to do so since John Wooden’s great UCLA teams of the late 1960’s and early ‘70s.

During his years as a Duke assistant, his name surfaced as the preferred candidate for many coaching vacancies, including those at Alabama, the University of Southern California, Northwestern and UCLA. In 1997, at the age of 31, he accepted his first head coaching position at Seton Hall, a school that had a two-year post-season drought.

In only his third year at Seton Hall in 2000, Amaker led the Pirates to the Sweet Sixteen and subsequently secured the nation’s top recruiting class. A season later, he accepted the head coaching position at the University of Michigan.

And for the first time in his basketball life, he was the subject of vitriol and invective when he resigned and announced that he’d be taking over the Wolverines program.

“It was all about Tommy, all the way to the end,” wrote Adrian Wojnarowksi, the current Yahoo Sports columnist who was then with the Bergen (N.J.) Daily Record. “For so long, he seemed so charming and sincere, but he slipped out of Newark Airport on his way to Ann Arbor so much less.”

In the Asbury Park Press, Bill Handleman wrote, “It wasn’t supposed to be like this. But because he did such a smashing job, Amaker had to crawl out of here on his belly, a reptilian bust. So here we are. Amaker lies to the kids he recruited, and he slinks off to Michigan, and he leaves Seton Hall in worse shape than he found it.”

The negativity bothered him, especially knowing that no one on the outside was privy to the conversations he had with his wife and trusted advisors about the difficulty of the decision.

“Seton Hall was a great place and they treated my wife and me very well,” said Amaker. “I was very fortunate to have my first opportunity there as a head college coach. It was hard for us to make that change. Those are life-altering decisions that you make and they are never easy.”

Despite the great opportunity and rise in stature that the Michigan job presented, Amaker agonized about the negativity that surfaced in the wake of his resignation.

“You certainly don’t expect everyone to understand,” he said. “It’s a public job, so those decisions will be debated. I understand it. But it was never easy, how the circumstances unfolded. But you respect and love the opportunity that you had there. I cherish those moments, even today.”

Feeling down, he called his mom and said that he’d just had the worst day of his life. He then headed for that one place in the African-American community that is equal parts comedy club and psychiatrist’s office – the neighborhood barbershop. As his barber tightened up his fade, listening to Amaker wonder if he let everybody down, he said, “Coach, you’ve got to look at it another way.”

“What do you mean by that,” Amaker asked above the thin din of the clippers.

“Coach, you don’t want people cheering and clapping when you decide to leave,” his barber told him. “The fact that they are upset means that they really cared, and that you did some really good things.”

To be continued….

Series Intro: Ivy League Hoops, Ahead of the Curve in Coaching Diversity