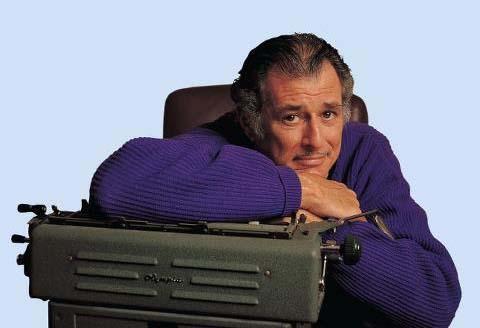

Frank Deford, the best sportswriter there ever was, passed away today at the age of 78.

He was someone I’d longed to meet and talk to, but never had the chance. I wanted to let him know that he raised me, in terms of how I thought about these games I love and to see beyond the final score into the humanity of those we cheer for and against.

You see, the greatest gift that my mother ever gave me was a subscription to Sports Illustrated when I was in the third grade. She saw how I gravitated toward athletics at a time when my world, our world, had been turned upside down. She noticed how not only playing organized sports, but also just being in the neighborhood with my buddies playing on the sandlot, gave me a sense of self-worth and confidence.

I’m sure she worried about me being outside of the house so much, but took solace in the fact that if I wasn’t at practice, she could look out of our 11th story window and see me playing a game of “kill the man with the ball” with my boys on a nearby patch of grass that we pretended was Shea Stadium.

If I wasn’t there, I had to be nearby shooting Skelly, playing stickball or wiffle ball, or behind the building shooting hoops, or perhaps slap boxing while pretending to be Sugar Ray Leonard.

Trouble wasn’t really my thing as a kid, contrary to my older brother, who was on a first-name basis with local law enforcement by the time of his reckless adventures of ninth grade truancy. If you saw me after school, I had some type of ball in my hand, or a baseball glove, or I was running over to the local boxing gym.

Sports gave me the structure I needed, and positive male role models that taught me about discipline, the importance of practice and the joy of working with others to achieve a common goal, and even that in loss, there is victory if you tried your absolute best.

She noticed that all of my book reports were about sports figures, as I’d walk the mile or so to the local library and come home with books that fascinated me with their tales of O.J. Simpson, Joe Namath, Muhammad Ali, and many others.

So when that Sports Illustrated mag began arriving every week, I devoured it. That’s when I fell in love with the written word, and began to see the story behind the story, that the games were about much more than the final score. They were, at their core, about people: flawed, dynamic, talented and vulnerable.

And it was because of Frank Deford that I began to understand the most powerful narrative in all of sports – its humanity.

Deford began writing at Sports Illustrated in 1962 and had two lengthy stints there. From 1962 to 1989 and from 1998 until his death, his signature was the longform story that I came to love.

He also worked with NPR’s Morning Edition for 32 years. He retired earlier this month following his 1,656th NPR commentary.

Deford’s writing was remarkable to me, because I’d walk away from his textured, nuanced pieces feeling as if I knew who these people, these folks who seemed larger than life, were. From Bear Bryant to Bobby Knight to Jimmy Connors and everyone else in between, whatever my preconceived notion was, I felt like I’d just sat down and had an intimate conversation with them.

When President Obama awarded Deford the National Humanities Medal in 2013, he said, “A dedicated writer and storyteller, Mr. Deford has offered a consistent, compelling voice in print and on radio, reaching beyond scores and statistics to reveal the humanity woven into the games we love.”

He wrote more than a dozen books, crafted TV segments for HBO’s Real Sports and, from 1990 to ’91 was the editor-in-chief of the The National, America’s first and only all-sports daily newspaper. He was elected to the Hall of Fame of the National Association of Sportscasters and Sportswriters in 1998. He was also voted by his peers as the U.S. Sportswriter of the Year six times.

His greatest gift to me was the beauty and simplicity of his writing. Throughout the years of my own professional journey, I believed that if you wanted to be the best, you have to study the best. And I made it a practice to read and re-read the works of the masters: David Halberstam, Hunter S. Thompson’s piece on the Kentucky Derby, John Updike’s piece on Ted Williams, Al Stump’s remarkable tale of Ty Cobb’s last days, Deford and many others.

In Deford, I realized that a great story didn’t have to focus on someone famous. In fact, I much more enjoyed his works on people that I’d never heard of before.

Among my favorites was a 1984 Sports Illustrated piece on a football coach at East Mississippi Junior College named Bob Sullivan. His nickname was Bull Cyclone.

If you’re unfamiliar, read it. The problem with today’s sports culture is that, as a whole, we’ve gone away from real storytelling and into the abyss of TMZ, television hot takes with bulbous headed loud-mouths and the microwaveable Twitter-fication of what was once a true art form.

Deford was simply a great American storyteller, a true artist who used words to summon emotion, who made you see, who made you feel.

“Coach Bob “Bull” (Cyclone) Sullivan was a legend in his place,” Deford wrote in the story’s open. “That place was Scooba, Miss, in Kemper County, hard by the Alabama line, hard to the rear of everywhere else. He was the football coach there, for East Mississippi Junior College, ruling this, his dominion, for most of the ’50s and ’60s with a passing attack that was a quarter century ahead of its time and a kind of discipline that was on its last legs. He was the very paradigm of that singular American figure, the coachcorch as they say in backwater Dixiewho loved his boys as he dominated them, drove off the weak and molded the survivors, making the game of football an equivalency test for life.”

Frank Deford was much more than a writer. He was a critical thinker with an eye for detail that elevated sportswriting to a level of rare art.

And we’re all, at least those of us that love masterful storytelling, much better and smarter for who he was, what did, and what he wrote.