Benny Douglas was standing near a camera holding a walkie-talkie on the set of Woody Allen’s untitled work in progress in the early 1990s. He wasn’t a director, but he was unintentionally working on his acting chops by pretending to be one.

Douglas, a young man with a wide smile and movie-star good looks was fresh out of college and trying to make it in the movie business. He had worked as a production assistant and watched Bruce Willis’ brilliance on Die Hard. His experience on Allens set was already turning out to be different.

A group of men had come by the set demanding that Allen hire black workers. The leader, Mustafa Majeed, along with sometimes as many as 40 men and women would travel around to various movie sets in New York City and cause a ruckus, standing in front of cameras and pulling electrical cords if there were no black or Latino employees.

Most film and television production jobs were held almost exclusively by white trade-union members.

“The main guy was sort of like a shake-down artist,” Douglas said. “I think he eventually got arrested for it.”

But for now, Majeed was generously offering arrangements for directors and production managers to pay him to find black crew members, particularly high-ranking crew members. In anticipation of them coming on that day, Allen had moved Douglas near a camera so he could look like a director rather than a lowly production assistant.

As duplicitous and racist as it was for Allen to pretend to have a progressively diverse set, it would be the perfect set-up for what was to come.

***

“Get lower,” Benny says to the actress Annie Honzeh playing Kidada Jones, Quincy Jones’s daughter who dated Tupac and would become his fiance before his death.

They’re in the middle of a love scene in a makeshift Luxor hotel room for the highly anticipated Tupac Shakur biopic, All Eyez On Me.

There’s a guy walking around offering parfaits to members of the crew. In another area, crew members are playing pool and talking trash during breaks.

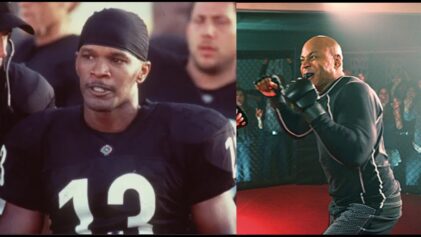

Demetrius Shipp Jr., who plays Tupac, bops around in a gray robe, blue socks and flip flops. Shipp’s tightly curled eyelashes, high cheekbones, tattoos, diamond nose ring, thick eyebrows and toothy smile are all eerily reminiscent of the rap star that hes portraying in the movie.

(Demetrius Shipp, Jr, left and Tupac, right, Photo Credit: truestaris.com)

So much so that when rapper Treach came to visit the set of the highly anticipated biopic, he broke down crying as soon as he saw Shipp.

Unlike on Allen’s set, Douglas sits in the director’s chair surrounded by crew members, many of them black, including L.T. Hutton, a former producer for Death Row who put up some of the money to help make this biopic happen with his production company, Program Pictures.

Tupacs mother, Afeni Shakur, who died last month from a heart attack, was the executive producer of the film.

People who have been with Douglas along his circuitous ride in the movie and music business are always close by, from his college friend, Gerald Rawles, who is his manager, to old b-boy buddies like Special, who impressed the crew with his charisma and thug credibility so much that he earned a role as an extra in the film.

This is the film that has needed to happen, but almost hasn’t too many times to count.

Other directors have bowed out of the film, including a very public quitting on the part of John Singleton, who felt that people involved in the project weren’t respecting Tupac’s legacy. House of Cards and Devil in a Blue Dress director Carl Franklin followed Singleton, but left quietly after a $10 million breach of contract lawsuit regarding budgeting and casting.

A month later, Benny Douglas, formerly known professionally by his nickname, Benny Boom, a veteran music video director and director of the comedy Next Day Air, was hired. Douglas named the untitled biopic, All Eyez On Me and began work with the stunning doppelgnger Demetrius Shipp Jr. as Tupac.

Douglas contends that he has an intimate commitment to the film that goes beyond just filmmaking expertise.

He really represented our generation, Douglas says about Tupac. Hip-hop was our voice. It was the way you wore your sneakers and clothes and your style. Not having instruments and scratching a record to make a beat because you cant afford drums. Thats not by accident. Tupac represented the voice of the voiceless.

“Benny should have been the first choice, his experience, his age, the fact that we personally know a lot of the players,” said Mike Ellis an assistant director who first met Douglas on the set of Spike Lee’s Clockers. “We were there. When he died, it changed our lives. It was our lives.”

On set on an uncomfortably cold and rainy day in Atlanta, Georgia, Douglas is inside a warehouse under the klieg lights, in the shadow of a replica of a rolling Las Vegas skyline that extends a few hundred feet across the wall. All around him are reminders of a time when hip-hop represented both the best and the worst in us.

A few yards away from where hes sitting is a replica of Quad studios where some of the best beats and rhymes in hip-hop were created, from Jay Z to Missy Elliott to DMX, Biggie, LL Cool J and many others. The elevator stands open, the floor caked with fake dried blood, a nod to the tragedy of a rap legend that endured being robbed and shot five times, twice in the head, twice in the groin and once in the hand in November of 1994.

The shooting occurred a day before the verdict in his sexual assault trial. I was covering the case as a reporter at the time. As Tupac lay on the operating table, the jury was asking for transcript read-backs. A day later, his mother would check him out of the hospital. With a Yankee cap tilted over his bandaged head, he made his way into the Manhattan courtroom in a wheelchair to hear a guilty verdict.

Right now Douglas is a few yards away from that set and a few days past filming that court room scene. He is all seriousness as he leans forward in his director’s chair looking at the monitor. The pressure is high to get Tupac’s story right.

The activists that shaped his point of view are anxious, the artistic mentors that shaped him as an intellectual poet, rapper, dancer and actor want to make sure his artistic temperament and sensitivity shine through. And the streets want to make sure Tupac’s take-no-prisoners edge gives them a voice.

Of course, it’s a Sisyphean task to tell Tupac’s complicated story.

Tupac was a man that could dance ballet at a performing arts high school, put out four platinum selling albums, star in six movies and be convicted of sexual abuse. He was a man that answered the question of what he wanted to be when he grew up at 10 years old with a simple answer: a revolutionary.

He loved hard, from strangers he flew to in an instant in order to help them, an 800-number he set up for kids to call him with their problems anytime, to his fiance who he sent an original poem and a rose to every day.

He was a man who could dissect the movie, Terms of Endearment and read and recite from memory Edgar Allen Poe, ancient Chinese philosopher Lao Tzu and Shakespeare, while just as easily blow up, spit at and push reporters, and beat down the filmmakers the Hughes brothers.

On set, Douglas speaks gruffly, deeply and authoritatively into his headset. He doesn’t do a lot of chatting with the crew between scenes, but there’s an air of amiability and of camaraderie between him and the crew.

He hasn’t undergone any public scrutiny or earned a reputation of being hard to work for like directors David Fincher, Francis Ford Coppola, Oliver Stone or Spike Lee. Of course, he’s still green, but it’s clear by their reverent glances that the crew both like and respect him.

“Rolling, Rolling!!!” Douglas calls out as a hush falls over every inch of the set.

The actress playing Kidada is on top of Shipp leaning towards his face.

“Give me a little smile before the kiss,” Douglas calls into his headphones.

The camera pans out above her black panties.

“Music!” Douglas yells. Aaliyah’s breathy love ballad “At Your Best” surges over the couple. The camera pans to the window overlooking the Vegas skyline and the scene ends.

It’s easy to see how when Douglas looks into the camera at Tupac’s character, he sees a little bit of himself.

***

Born in West Philadelphia, Douglas would move with his family to Mount Airy and North Philly. For a few years, he lived in Texas with his father.

In Houston, he found himself getting into fights regularly, using violence as a reaction to racial tensions.

“I didn’t feel like I fit in down there,” Douglas said.

Before long, he was running away with the help of an aunt that booked him a plane ticket on her American Express card, and back to Philadelphia where he finished high school at Overbrook.

In the 1970s, Philadelphia felt like the last bastion of racial segregation north of Baltimore to Douglas. His family bought their house in Mt. Airy from a Jewish family when he was a little boy. Every day after getting off the school bus, he would stay with an old Jewish couple who lived next door until his mother came home.

But soon white flight took over. By the late 70s the whole area was black.

As an only child of a single mother, he spent a lot of time collecting comic books, daydreaming and making up stories to ease his loneliness. He would fall asleep to his black and white television at night to shows like The Honeymooners and Johnny Carson, with the images and stories seeping into his dreams.

His second home was the ornate Art Deco styled movie palace alternately called the Bruce Lee Theater and The Sam Eric Theater, located in downtown Philly, which at one time hosted world premieres like The Wizard of Oz, The Battle of the Planet of the Apes, Rocky III and Philadelphia.

(Photo Credit: 2warpstoneptune.com)

“On Sundays, it turned from the Sam Eric to the Bruce Lee Theater so you could see two movies for two dollars,” Douglas remembers. “For just five dollars you could get on the bus, get on the train, go to the movie and get popcorn, candy and soda. We were just a bunch of kids from like 8 years old, the oldest was maybe 13.”

Two movies that played at the same time that resonated with him was the cult classic New York street gang movie, The Warriors, and Young Blood starring Lawrence Hilton Jacobs, who plays an ex-Vietnam vet that moves back to Los Angeles to run his neighborhood gang.

Though Philadelphia had a burgeoning rap scene with artists like Schoolly D, King Britt, Three Times Dope and Jazzy Jeff and The Fresh Prince, it was in Texas that Douglas would become fully immersed in hip hop.

It was where he would adopt his rap name, Benny Boom, after one of his boxing idols, Ray Boom Boom Mancini.

“I was a huge boxing fan,” said Douglas, who would watch the fights regularly as a kid. “Everybody wanted to emulate boxers. Ali was the biggest, but for our generation it was Sugar Ray Leonard, Tommy Hearns and Marvin Hagler. Mancini killed a dude in a fight. In my twisted mind, I’m thinking, ‘He’s way badder than any boxer!’ So I adopted his name.”

With a deadly new name, he hooked up with Tony, a Dominican kid from New York who was a skilled beatboxer, at a party. Tony had taped hundreds of shows off of WBLS radio in New York. He and Douglas would take the rhymes on the tapes that hadn’t been heard in Houston yet and rewrite them.

They would perform during intermission for groups and get paid, and battle and B-Boy, otherwise known as break dancing, at teenage clubs and at the mall using other rappers lyrics.

“It’s funny because now I’m working with LL Cool J,” said Douglas. “And we used to take everything from him.” When Douglas went back to West Philadelphia and finished at Overbrook High school with rappers like Fresh Prince, Steady B and Cool C, he was accepted to Temple University. But he didn’t accept Temple.

“I was in the middle of street stuff,” he remembers. “I didn’t need college. I thought I was smarter than I was.”

His mother’s uncle, who had dropped out of high school, helped him to get his head straight.

“He told me I had the opportunity to do something special that no one else in the family had done.”

It would take another year before he matriculated and dedicated himself to college life. His classmates would include actors Fred Thomas from the popular Budweiser “Whassup?” commercials, actor Maurice Smith and his good friend and fraternity brother Rawles, who would become a producer and actor, and eventually Douglas’s manager.

Douglas’s devotion to hip-hop didn’t just fade away once he enrolled. It would always be an integral part of his daily life. Eventually, he would be fully immersed in the golden age of hip-hop, behind the scenes and rocking the mic.

***

In the summer of 1994, Douglas had finished college and moved to New York to try to make a go at filmmaking. At a barbecue in the Poconos, he met aspiring rapper Hakim Green and ended up in a rap battle with him.

I spanked him around, Hakim laughs about it now.

After the cookout, Hakim didnt see Douglas for another three years. In the meantime, Hakim got a record deal with Capitol Records and was being managed by KRS-One, for his rap duo with Vincent Tuffy Morgan, Channel Live.

When they eventually ran back into one another in Brooklyn, Douglas became the unofficial third member of Channel Live, freestyling with them and starting a company together called Illegal Broadcasters.

Douglas, Hakim and AJ Calloway were roommates when Channel Live signed with Flavor Unit in 2000. Douglas was still hustling as a production assistant hoping to move up the ladder and had just had his first son.

But he had long vision. He didnt believe in working odd jobs to make ends meet. He would just coast without money until he got a call to be another set.

It was always a hustle working in production, remembers Gerald Rawles, his friend from college who would be his roommate in New York and eventually his manager. I remember eating the same meal every day for weeksa turkey and cheese sandwich and a box of Entenmanns chocolate chip cookies from the corner bodega.

“I slept on a lot of couches. If it wasn’t for friends and my fraternity, my shit would be fucked up,” Douglas said.

Shakim Compere, Flavor Units co-founder, wanted Q-Tip to shoot Channel Lives first video.

I said, If Q-Tip shoots the video, Im not showing up. I wanted Benny to shoot the video, Hakim remembers. I said, If hes not shooting the video, theres gonna be problems.

I was like: If my man has the ability to pull off the job, I want my man to get the job. Shakim and Latifah, youre just gonna have to ride.’ Because I was in a position of power, I was gonna make sure my man got the look.

At the time Douglas had nothing to show for the expertise required to shoot the video — no slide show and no reels — just a confident belief in himself. He hadnt even written a treatment before. Hakim planned to give Douglas the $50,000 from their budget to shoot the video, but Douglas boldly insisted that he needed $100,000 to execute it properly. They took the remaining $50,000 from their promotion budget and were left with nothing.

“We couldn’t go out on the road and tour. We couldn’t do any promotion,” Hakim remembers. “I literally ended up homeless. I had to take a step back and put my career on the shelf and get behind Benny and hope and pray.”

“No one was shooting 100K videos for an independent rap group,” Douglas said. “It was Hakim that said, ‘You gotta put your name on the video. Hype does it. You gotta promote yourself.'”

The video Wild Out2K” opened with the words “Benny Boom presents” in the way that Hype Williams included his name as an intro to his music videos. It was a hit with audiences and industry heads.

“A friend of mine, the VP of Violator, said to me: ‘I’m managing LL and if things go my way I want Benny to do LL’s video project,” Hakim remembers.

Douglas directed LL’s videos “Luv You Better” and “Paradise” and soon after, “Oochie Wally” for Nas.

One day he got a phone call from Hakim, who was on his way to Puffys soul food restaurant, Justins, on 21st Street in Manhattan. As Hakim was walking out the door of his apartment, he heard on the radio that rapper Nelly was doing a promotion at the popular eatery.

Yo, Nelly is gonna be at Justins. You gotta go. You gotta go.

I cant find a babysitter. You gotta lock that down for me, Douglas told him. His five-month- old son was within eyesight.

He ended up shooting Nellys Number 1 video, which turned into seven other Nelly videos.

The next call he got was for Nas for the record Got Urself. It was 2002 and the murders of Tupac and Biggie were still fresh. Jay-Z and Nas were in the middle of a beef, started because of many reasons, one of which was that Nas reportedly turned down a guest spot on Reasonable Doubt.

The two of them began a lyrical battle of proportions that had not been seen since the Bridge wars.

Douglas was nervous about coming up with the right idea for the video. A Sony executive had given him the job, but he still had to pitch it to Nas.

Douglas and Hakim were up until 3:00AM brainstorming. Since Nas is talking to Jay-Z in the record, they wanted to visually represent that without being obvious. First they thought to do a re-enactment of the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X with Nas as Martin and Jay as Malcolm.

But they needed something more relevant to this generation.

“How about Biggie and Tupac?” Hakim asked.

They both looked at each other.

Yoooo, thats it!

Rawles and Douglas wrote the treatment, taking the last known photos of Tupac and Biggie and re-enacted the moments before the photos were taken.

The ultimate message was that Jay-Z and Nass beef should be squashed before it ended in the same way.

It was risky to approach it and attempt to do it. The murders were still fresh, remembers Douglas.

Puffy had seen a rough cut and approached Douglas in a club about it.

“He was like: ‘Yo, playboy, how you gonna make a video with Biggie dying and you dont talk to me??!!

I didnt feel like I had to answer to anyone like that, Douglas said. I was part of the hip-hop community. Im not an outsider. Im living and breathing it every day.

I said, With all due respect, this is Nas video, you have to talk to him.

Douglas ended up talking to Nas and making the changes out of respect for the situation. Two months later Puffy called him and offered him four music videos.

That Nas video, thats when Benny kicked the door in, Hakim remembers.

He followed it with Nas’s “Made You Look”, which featured passages from Rudyard Kipling’s poem, “If.”

“Nas shooting that video was the victory lap between him and Jay Z. Rudyard wrote that poem for his son who was in the First World War, Douglas said. Because Kipling was an atheist he couldn’t give him any scripture, so he wrote that poem for him to take into battle. It connected so much to the opening of that video because of what it meant historically.”

Douglas would work as an assistant director for Hype Williams, Paul Hunter, and Little X, among others and directed hundreds of his own award winning videos for hip hop and R&B’s finest, including Nicki Minaj, Amerie, Kelly Rowland, Keyshia Cole, Lil’ Kim and 50 Cent.

When he first started directing videos, the landscape for hip-hop videos was focused around materialistic escape fantasies with images of expensive cars, exotic looking women and money being thrown around. Douglas set himself apart by telling stories.

**

In 1995, Mike Ellis met Douglas on the set of Clockers at the Gowanus Houses in Brooklyn.

“He was like an enforcer. He was big and strong and had these long dreads and he was fearless,” Ellis remembers about how Douglas doubled as security for the set. “We would be out in the projects and I’d send him to go get rid of 200 people. And he’d do it. In the projects!”

Ellis remembers when he worked on Douglas’s second film after Next Day Air, entitled S.W.A.T.: Firefight. They were talking with other crew members about doing a scene and Ellis didn’t have to look at his papers to remember what scene and what the dialogue said.

“Benny was like, ‘How did you do that?’ That next Monday Benny had everything memorized.”

He has an encyclopedic recall of films Ellis says, and can recite the names of actors, directors and crew members for hundreds of films. According to Ellis, Douglas is never late to set. He’s always prepared and when that plan fails, he’s prepared for plan B.

“He’s gonna show up and spread the love and make people want to do their job,” said Ellis. “People want to work for Benny because he’s open. He’s never standoffish or unaccommodating. And his loyalty is ridiculous. People that are down with us from back in the day are still down with us.”

“Benny and I used to go to the same hip-hop clubs – Kilimanjaro, Mars, Muse, Palladium. In the 90s, every day of the week there was a club to go to,” remembers rapper Masta Ace. “He’s a fan of this music. He wasn’t some fly by night director that got handed this film. He was in the club dancing to it. He knows what it looks like, he knows what it smells like, he knows what the atmosphere was. I just know he will put his own experiences into it and make it come to life.”

“All of the times I spent as a PA, working, sweeping floors, all of these things helped prepare me for this movie,” said Douglas, who is now married with three kids.

**

Afeni Shakur, as the executive producer of All Eyez on Me, had the chance to witness the making of the film about her son’s life. In April, the film wrapped.

Afeni would die from heart failure a month later.

The actor Demetrius Shipp Jr.’s father, Demetrius Shipp Sr., was a producer for Death Row and produced the song, “Toss it Up,” on the Don Killuminati album. His first gold album was for the soundtrack for Juice, Tupac’s movie debut, where Shipp produced the cut, “Flipside.” His son hung around Death Row as a kid with the likes of Suge Knight.

As an actor, the young Shipp doesn’t just look like Tupac, he embodies him — talking like him, with the same mannerisms, the same crazy walk.

“I think we are going to freak some people out when they see this movie,” said Douglas.

Although it has taken many years to get the film off the ground, Douglas says this is the way it was supposed to happen. Tupac would have been 45 years old on June 16th.

“He was born a month before me,” Douglas said. “Every step of the way…the stuff he went through I can connect to because I went through something similar during those years.”

“This movie is coming out at the perfect time because Chicago is out of control, Douglas continued. St. Louis is out of control. Baltimore blew up. Pac is every kid in the ghetto that had a dream, that didn’t have the best circumstances growing up and made something out of himself. Given the mistakes in our 20s…look at Jay Z and Nas and how they’ve transformed hip hop. People that are younger love Pac and miss him for what he was. People our age love and respect him for what we think he could have been.”