Last week, author, activist and former NBA player Etan Thomas and the Kinnon Group, in conjunction with Canaan Baptist Church of Christ, held a Fatherhood Panel in Harlem, New York before 6th and 8th graders from the New York Public School District who are considered “at risk.”

In other words, they are beautiful black and brown children from economically disadvantaged and disenfranchised backgrounds.

The Shadow League has always had an affinity for athletes who are actively involved in the community, and are aware of all the pitfalls, traps and real life monsters that await children from inner city backgrounds.

In order to properly break it down for the crown, Etan Thomas gathered a menagerie of former professional athletes who could have easily found themselves in the police blotter of local newspapers, in prison or in the city morgue had it not been for a key decision or two.

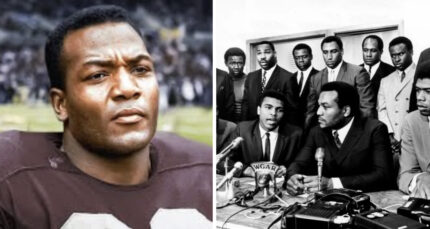

(John Wallace, Louis Orr, Etan Thomas, Keith Bullock, Roosevelt Bouie)

On hand to give testimony were former WNBA All-Star and author Chamique Holdsclaw, former New York Knicks small forward and Syracuse Orange standout John Wallace, 13-year NFL vet and three-time All-Pro linebacker Keith Bullock, legendary griot Abiodun Oyewole of the Last Poets, former Syracuse Orange basketball standouts Louis Orr and Roosevelt Bouie, as well as poetic offerings from Danny “Versatile” Crawford, Messiah Ramkissoon, and Thomas’ very own progeny Malcolm Thomas.

Chamique Holdsclaw was the first to take the microphone and share her testimony.

“Here I am, this young kid, born into a situation where both my parents were homeless,” she said. “So, I’m watching my parents go into a state of dysfunction. Here I am, me and my brother are both kids, the police knock at our door. The next thing you know we can’t live with our parents anymore.”

Holdsclaw went on to explain that she had to move to the Queensbridge Houses to live with her maternal grandmother.

“The girls that I went to school with would be like ‘Don’t hang with her,'” she said. “They would come on the basketball court and try to beat me up. And I was scared. I was six-foot-two, I’m a big woman but I was so scared. I was jumped, I was beat up all the time. But I knew I wasn’t going to be dealing with this my whole life. I knew I wasn’t going to be living in those housing projects my whole life.”

“I was trying to figure out what’s the fastest way outta here,” she explained. “My grandmother would say basketball is not the way out but school is. She was strict. Before I could go outside I had to do my homework first, but I became good at basketball too. It became a distraction for me because basketball was my coping mechanism. That’s where I took out all my anger and frustration.”

“When you come home and everybody in the projects is teasing you because your mother, the night before, was sleeping on a park bench and everyone is making fun of you, the only thing i knew was ‘Go do my homework then take my ball and leave it all out there.’ And I became better and better. I never played with girls. I don’t know if any of y’all know, but it wasn’t cool for girls to play basketball in the 90s.”

Former Syracuse standout John Wallace is remembered by NCAA basketball aficionados for guiding the Syracuse Orange to an unlikely NCAA championship game in 1996. He has been working with the New York Knicks for the past seven years after a seven-year NBA career. Additionally, Wallace is an Executive Board Member of Heavenly Productions, a nonprofit organization whose charter is to help kids in distress.

Like so many who testified, Wallace can trace his current path in life to one fateful decision decades ago.

“I was headed down the wrong path for a very long time,” said Wallace. “Things were not going well in my life and I started feeling sorry for myself. My father was not around, my mother was working all the time and I wanted to try to help her out. So, when I was like 11 or 12 years old, I started stealing cars pretty much everyday of the week. I was stashing them in certain locations and taking some to the chop shop to get money to help put food on the table for my mom.”

“One particular night, we stole a car and we were going to get $5,000,” Wallace continued. “When you’re from the hood and don’t have two dollars to rub together, that was going to be our way out. We actually thought we were going to sell this car and move to Hawaii. That’s how shortsighted we were.”

“Something happened that night that changed my life forever,” he said. “My cousin Tremaine and my boy Lamont, they wanted to pick up some girls and joyride and show off. I just didn’t think that was the smartest thing to do. It wasn’t the smartest thing for three young black men to drive around the hood in a brand new stolen car. So, I got out of that car. 15 minutes later, my cousin Tremaine and my boy Lamont were arrested. From that night forward, I dedicated my life to basketball.”

For quite some time, panel moderator Etan Thomas has been hosting events designed to spark the minds of young people from economically disenfranchised communities. He is quickly becoming as celebrated for his social activism as he was for his shot-blocking prowess while at Syracuse.

Following his stop in Harlem, Thomas took the show on the road and hosted a similar panel in Glenn Hills, Maryland that featured former Georgetown Hoya standout and New York Knick Michael Sweetney, Dr. Lonise Bias (mother of Len Bias), Robert Griffin II and others.

“We’re going to be doing a lot more of these in the future and connecting with more schools,” Thomas told The Shadow League. “This is good because a lot of these accomplished people, young people don’t know the mountains they had to climb to get to where they are. We probably could have been in there for another two hours, especially after we started letting the children ask questions because it energized them. It became a ‘no judgement zone’ because we shared all our stuff so they felt comfortable in sharing their situations.

“I have a passion for doing these types of things,” Thomas continued. “I do it in June, February for Black History Month, and in September when it’s time to go back to school. Those three months are when I really start putting it in.”