This is part of The Shadow League’s Black History Month In Focus series celebrating Black excellence in sports and culture.

The vast majority of elite players in high school, college, and professional basketball are Black. Keeping it a zillion, Black folks have so thoroughly dominated the American game over the decades that the National Basketball Association now has had to import white players from other countries.

However, the deeper and more substantive connections into the very DNA of the game of basketball are blacker than most know. Unfortunately, we live in a society that loves bells and whistles and shows disdain toward recognizing the more cerebral and cultural contributions of men and women of African descent.

So, as part of The Shadow League’s Black History Month in Focus, I present Three Little Known Black Basketball Facts.

The Inventor of the Fastbreak

The late great basketball coach John McLendon has gotten his proper respects as a forefather to the modern proliferation of Black basketball coaches in the NBA, and at collegiate programs to a lesser extent, but did you know he was the progenitor to the very concept of uptempo basketball?

One of a very exclusive group of basketball coaches who received personal instruction from the game’s inventor, Dr. James Naismith, McLendon’s Tennessee State teams were the first to incorporate the fastbreak, as well as the halfcourt trap, which would lead to more points in an uptempo game that was revolutionary when first unveiled.

It seems rather regular nowadays. Back then? Unheard of.

The Hidden Legacy of Coach Dean Smith, Fiery Activist

For many hardcore basketball fans, the late University of North Carolina head coach Dean Smith is remembered as one of the greatest coaches of all time, while younger fans may know that he was the head coach of one Michael Jeffrey Jordan during his college days.

But did you know Dean Smith was, as the kids say, woke? Yup! His moral stock was brolic! He urged Topeka High coach Alfred Smith, his father, to integrate the school’s two basketball teams. The school fielded two separate teams back then, the Trojans, which was all white, and the Ramblers, which was all Black.

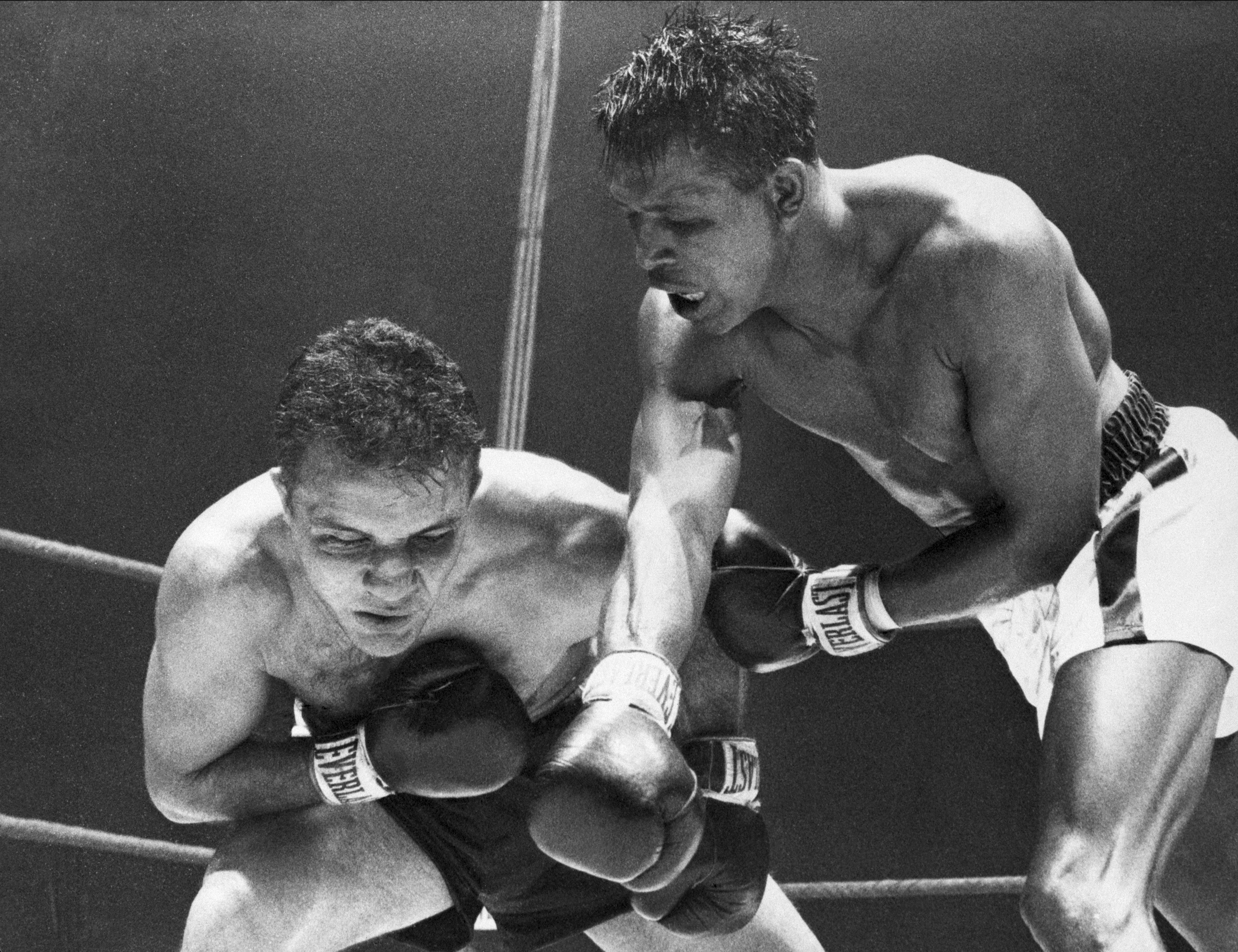

(Photo Credit: Getty Images)

This happened in 19 “friggin” 40! Amazing! He also recruited Charlie Scott, who was the second Black player to ball in the Atlantic Coast Conference and the first Black Tar Heel, in 1966, and once had to be restrained from entering the stands to fight a fan who called Scott a racial slur.

Smith worked tirelessly to eradicate racism and bigotry. He even spoke about nuclear weapons proliferation and the paradox of injustice posed by the prison industrial complex. This was decades before most of us even realized what it truly was. We could use a million more Dean Smiths about now.

The First Integrated Basketball Game

Did you know the first integrated college basketball game was a secret?

The game, which took place in 1944, had regular officiating and a clock and was actually illegal at the time. Coached by the aforementioned 28-year-old coaching phenom named John McLendon, the North Carolina College of Negroes, now North Carolina Central University, had only lost one game all season. However, there was no way that the National Invitational Tournament or the NCAA were going to let Black players participate.

So, coach McLendon used this game against a group of former star college players who were competing for a military team based out of Duke University’s medical school as his championship.

The final score was Eagles 88, Visitors 44. No scorecard exists but here’s what white player Jack Burgess, who played for the University of Montana and was heavily recruited by University of Kansas coaching legend Phog Allen, had to say about the affair.

“Oh, I wonder if I told you that we played basketball against a Negro college team,” Jack Burgess wrote to his family in Montana a few days later. “Well, we did and we sure had fun and I especially had a good time, for most of the fellows playing with me were Southerners. . . . And when the evening was over, most of them had changed their views quite a lot.”