Atlanta Dream rookie guard Shoni Schimmel rarely loses focus and intensity on the basketball court. But for one flickering moment on May 30th, in a game against the Seattle Storm that Friday evening at Philips Arena, she experienced a surreal sensation.

The string of dizzying events over the past few months had collided and melded in such a way that Schimmel was left with sparse time for reflection. After concluding her college career with a brazen, audacious, 31-point, five-rebound, four-assist performance in the University of Louisville’s 76-73 loss to the University of Maryland in the NCAA Tournament’s Elite Eight, she was drafted by the Dream with the eighth overall pick in the WNBA Draft two weeks later.

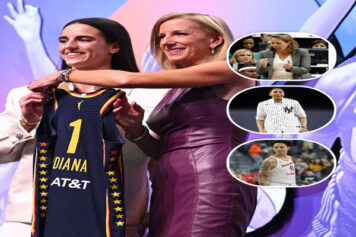

On draft night, when she stood on the podium at the Mohegan Sun hotel in Uncasville, Connecticut holding up her new jersey alongside WNBA President Laurel J. Richie, the pride and the magnitude of the accomplishment were not simply relegated to the beaming joy emanating from her cherubic face.

There was another powerful, multi-generational source of inspiration buttressing her smile as well, symbolized by the beaded turquoise earrings and matching bracelet that adorned her earlobes and left wrist, along with the necklace that had a Native American design woven into a cross.

“The jewelry belonged to my great-grandmother and my grandmother,” said Schimmel. “They weren’t able to be there, along with many of my other family members. But to be able to wear something that represented them, it was almost like they were there with me.”

Less than two weeks after the draft, Schimmel was in Atlanta’s training camp. Within a month, she was playing in her first basketball game as a professional.

“With the draft being right after the college season, it was a very quick transition from playing in college to being a pro,” said Schimmel.

Within the rapid swirl of her swiftly changing life, she needed to relocate and acclimate herself to a new coach, teammates and a foreign city, along with an organizational structure that was far removed from the nurturing cocoon of her college experience.

Despite the whirlwind of change, there was basketball to be played, immediately, against the best players in the world. And Schimmel proved up to the task. In Atlanta’s second game, a 90-88 road victory over the Indiana Fever, she sizzled with 17 points, 10 assists and two steals. In the next game at Chicago, she scored 17 again, while grabbing five rebounds and dishing out eight assists.

But it was two games later, against Seattle, where Schimmel had to pause, blink and re-focus, when the immensity of her accomplishments coalesced and caused her to pause in her tracks.

“We’re playing against the Storm and I saw myself standing next to Sue Bird,” said Schimmel. “I was like, ‘Wow! That’s Sue Bird!’ It was surreal. Seattle was close to Oregon, where I’d grown up. I loved her game and felt like I had a connection to her because she was one of my favorite players. I was like, ‘Whoa! I gotta stay focused on basketball. I can’t sit here and be star struck because we’re both in the WNBA now.’ So, I had to regain my focus and not think about who I was playing against.”

(Photo Credit: WNBA.com)

Schimmel’s rise to the pro game is far from a singular accomplishment, though. Her path was one that had never been traveled before, filled with the heartaches and struggles of not only her parents and their parents and their parents before them, but of millions of other Native Americans.

Shoni’s story is not merely a sports or basketball story. It’s a triumphant story of hope in the unseen, where through her gifts and hard work, she’s building bridges, dreams and hopes for many others.

THE ESSENCE

If you’ve ever been to a Native American basketball tournament and experienced the phenomenon of what’s called ‘Rez Ball’ – a hoops game characterized by a hostile, antagonistic, ‘80s-Lakers-Showtime-type of transition offense and a belligerent, ‘90s Bulls-style approach to pressure and trapping defense, you’ve been stricken, as I once was a few years ago, with an unexplainable sensation that is akin to being linked to the game’s womb, nourished by its umbilical cord.

Amid all of the heartbreaking occurrences experienced by Native Americans, it’s uplifting to experience the impact that basketball has on the community. It is now, as it always has been, a dynamic, empowering force to this country’s indigenous population.

In November of 1989, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, wanting to re-connect with the game that forged his legend, volunteered as an assistant coach for Alchesy High School on the White Mountain Apache reservation in Arizona. His reflections on the experience were consolidated in his book, A Season on the Reservation.

Abdul-Jabbar, whose mother was part Cherokee, was shocked at the pace the players maintained. He mentions, at various points in the book, “The boys were flying up and down the floor like pellets fired from a twelve-gauge shotgun…These kids went from zero to full speed in nothing flat…This was a new type of game altogether.”

If you’ve ever seen Shoni Schimmel play, that’s an apt description of who she is on the court. To virginal eyes, she plays a new version of the women’s game that hasn’t been seen yet. To those who’ve been exposed to ‘Rez Ball’, there’s nothing new about her style.

It’s been around, though hidden under the cloak of obscurity, for over a hundred years.

“In a way, it’s more their game than anyone else’s,” Kareem wrote. “Basketball is not originally a white or black game, but a Native American one, although most people don’t know that. Centuries ago, the Mayans and Olmecs played a form of the sport in Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula…The sport spread throughout Mexico and moved north, all the way to Arizona, where the Aztecs traveled and traded with the Native Americans…The inventor of modern basketball, Dr. James Naismith, gets credit for founding a sport that others had been playing, in one form or another, for hundreds of years before his birth.”

The Native Americans were also the first to be exposed to Naismith’s derivation of the sport.

“In 1892, Dr. Naismith’s YMCA colleague, H.S. Kallenburg, introduced the game to the Lakota Sioux,” said Dr. Wade Davies, the former Chair of the University of Montana’s Native American Studies Department. “So, Indians were playing the current game within a year of its modern invention.”

Corresponding to Naismith from a conference he was attending at Big Stone Lake in Pierre, South Dakota in the summer of 1892, Kellenburg wrote, ‘The Indians took to the game like ducks to water.”

The Indian boarding school movement, which began in the late 1800’s, was designed to assimilate Native American youth to American norms by means of comprehensive immersion.

“Within a few years of the turn of the century, Indian boarding schools all over the country were playing basketball,” said Davies. “The sport was appealing because most of the boarding schools were in rural areas, they were small and underfunded and basketball was really the only team sport that was feasible.”

In the repressive boarding school environment, athletics provided avenues for entertainment, self-expression, enjoyment and travel. Also unlike football and baseball, the country’s most popular sports at the time, hoops could be played by male and female, young and old alike.

“In the 1900’s, Indian kids were traveling all over the west, not only to other Indian schools, but they played against white schools and colleges as well,” said Davies. “In an era when racism was very pronounced, basketball was one of the only avenues where they were respected.”

THE UMATILLA THRILLER

Shoni was raised on the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation, home to the Umatilla, Walla Walla and Cayuse tribes near the city of Pendleton, on the north side of the Blue Mountains in eastern Oregon.

Reservations across the United States have chronic rates of crime, substance abuse, diabetes, tuberculosis, suicide and school attrition that far outpace the national average. But her family, which was low on cash yet rich with love, made every sacrifice possible for Shoni and her siblings to believe that they could reach for their dreams

“My parents sacrificed a lot,” said Schimmel. “They had to take certain things away from their lives to focus on us. My dream as a little kid was to play in the WNBA. They helped me stay on the right path. And my sister Jude was right there by my side. She was four years old and I was five when we started playing on the same team.”

(Photot Credit: NPR.org)

“They helped us stay focused and become the best that we could possibly be,” Schimmel continued. “There were endless practices and skill development work, a lot of repetitions of the same drills over and over. We never knew why we kept continually doing the same things, but as I grew up, I realized, ‘Oh! That’s why we did all that work.’ To sit here and watch how it’s all come together, how it has paid off, is pretty neat.”

Shoni’s mom, Ceci, always stressed to her children the importance of never letting others set limits for them. It was a lesson that she learned the hard way. A cross-country and basketball standout at Pendleton High School, college coaches showed scant interest, despite her level of talent that equaled, if not surpassed, her peers that were being recruited. The elite college programs were simply not offering many scholarships to teenage mothers, let alone Native American ones.

Her father Rick, who is Caucasion, was considered the top high school baseball player in the state of Oregon in 1987, when he was a talented shortstop and pitcher at Pendleton High. During the spring of his freshman year at Stanford University, where he harbored reveries of playing Major League Baseball, he learned that Ceci, who was still at Pendleton, was pregnant.

He transferred to Portland State after his first year at Stanford in order to be with the young lady that he loved, and the child that would soon be born. After their son Shae was born, Shoni came next, and then Jude. They would have five more children after them.

Basketball occupied a sacred place on the reservation, and the Schimmel’s immersed themselves in its nutritious spirit.

Shoni battled her older brother and father in fierce, brutal games of one-on-one.

“There was a hoop outside of my house that I literally played on all day and every night,” said Shoni. “It’s what we did to stay out of trouble. We had one of those hoops that you could lower, and I would dunk on it. I’d be out there practicing the tricks and fancy dribbling that I saw while watching the And1 mix tapes with my brother. Every day, I was out there with my cousins, sisters, brothers and the rest of my family.”

When her brother told her that girls couldn’t play with boys, she began bypassing women’s night at the local gym, choosing to get her runs in on men’s night instead.

During a co-ed tournament in Idaho, as an eighth grader, the boy guarding her became fed up with her daring, darting forays to the rim, her Allen Iverson-like crossover dribbles, the bombs that she routinely splashed from way beyond the high school three-point line, and the delicious, fancy passes that she delivered to her teammates for easy fast break layups.

He got in her face and intensified his defense, acting as if he was tired of playing around. With a smirk of amusement, Shoni passed the ball to herself off of his forehead and proceeded to sink a long jumper.

When Shoni and Jude emerged as two of the best players in the state during their respective sophomore and freshman seasons at Hermiston High School, their mother Ceci made a bold move. She’d coached her girls since they were little in AAU and Native American tournaments, and decided that she wanted to coach on the high school level.

Ceci applied to numerous schools, and was offered the head coaching position at Franklin High School in Portland. She struggled with deciding to accept it, because it meant having to leave the reservation.

“Honestly, life on the reservation is fun,” Ceci told Sports Illustrated in 2013. “Everyone knows each other, and it’s not about who has the fanciest car or house, because everyone lives check to check. It’s comfortable. I was afraid to leave, but this was my chance to show my kids, ‘Don’t ever let your dreams die.’”

“I love the reservation,” Ceci told the New York Times that same year. “But I wanted my babies to have a fair opportunity. Plus, I wanted to show people what I could do. Even though I didn’t want to leave the reservation, I told myself, ‘If I don’t do it, my kids are going to follow suit. They’re going to say, well, Mom never left, why should I?’ I wanted to show the kids that if you really want your dream, sometimes you have to go out of your comfort zone and go get it.”

The family’s experience over the next two years was captured by filmmaker Jonathan Hock in his gripping documentary, ‘Off The Rez.’

With Rick serving as her assistant coach, Ceci took over a Franklin team that had won only four games the previous year. Despite the fact that Shoni broke her foot and missed eight weeks during her junior year, the team finished 21-5 and advanced to the quarterfinals of the state championship tournament, propelled by her sister Jude’s outstanding play. The next year, with Shoni averaging a ridiculous 30 points, nine rebounds, seven assists and six steals per game, they went 22-5.

But the experience was far from a fairy tale. With their ostentatious, up-tempo, freewheeling, colorful style, they thrilled as many people as they polarized. Shortly after their first year in Portland, a handwritten note arrived at the home, addressed to the Schimmel sisters.

It said, “Go back to the F****** reservation.”

“I’ve dealt with it my whole life,” Shoni told The Oregonian during her senior year in high school. “At Hermiston, on my AAU team…ever since I was little, it’s been pretty bad. We’re a strong enough family to know there’s people out there who are always gonna be against us.”

One of the most sought-after prep recruits in the country, Shoni followed her mother’s example by stepping out of her own comfort zone to attend Louisville, a school situated 2,100 miles away from home.

But despite her early uneasiness with the distance, she felt comfortable committing to play for the Cardinals because they embraced her panache, inventiveness, ingenuity and unique flamboyance.

At the start of her freshman year, the coaching staff decided to forego easing her into her college basketball experience. Instead, they unleashed her. She started all 35 games, led the Big East in three-point field goals made, scored 33 points in a game against Xavier, was third in the conference in assists, averaged 15 points per game for the season, and helped lead Louisville into the Sweet 16.

But being away from her family, and not playing with Jude for the first time since she was five years old, tested her resolve.

“When I would go home, it was always so tough to leave,” said Shoni. “But I knew that staying at home wasn’t an option. There were a lot of people looking up to me. And so many great athletes from the reservations that got a chance to go to college never finished. Most of them returned home within a few months.”

“I knew that I had to go back to school,” she continued. “I loved playing basketball and had dreams that I wanted to accomplish. At the same time, I wanted to prove that Native Americans could leave the reservation and find success in the outside world.”

During her freshman year, the Louisville athletic department couldn’t help but notice that she had a rabid, built-in fan base that was pouring into the spanking new KFC Yum! Center. Native Americans were showing up en masse, traveling thousands of miles to get a glimpse of Shoni. At some road games, Cardinals fans began outnumbering the home crowd.

Jude joined her at Louisville the next year.

The Schimmel Show was back together again. They were poised to not only electrify their Cardinal and Native American fan base, but all of college basketball as well.

To Be Continued…Read Part II Here