If you missed Part I of The Shadow League's feature story on Ernie Graham, read it here.

When he arrived on campus in College Park, his transition to college basketball wasn’t as smooth as he assumed it would be. Graham felt that he should have been playing more during his freshman season, when Maryland finished with an overall record of 15-13. In conference play, they finished in sixth place with a record of 3-9.

“We used to go at it in practice,” said Graham. “We had some size and talent on that team. The basketball part wasn’t tough for me, though. The tough part was dealing with the politics and the fact that I wasn’t playing as much as I thought I deserved to.”

Adjusting to some different dynamics also proved challenging.

“I came from a different world,” said Graham. “I only saw white people in Baltimore when they were going to the Colts and the Orioles games at Memorial Stadium, which wasn’t too far from my house. And every coach that I had growing up was African-American. So that was a very profound cultural change that I had to get adjusted to, in terms of how I related to people, and my head coach.”

Graham played in 26 games his freshman year, but only averaged about six minutes per contest. He simmered internally, especially during home games at Cole Field House, where he’d look into the stands and see the faces of his rec league coaches and younger kids from the neighborhood.

“The Baltimore City Department of Recreation and Parks used to charter buses to bring the kids to my games during my freshman year,” said Graham. “Larry Gibson, who had played on those great Dunbar teams with Skip Wise, was an upperclassman with me on the Maryland team, and the adults from our community would bring all the kids from the rec centers to watch us play.”

Early on during the season, Graham found himself checking into games during the final moments, long after the final outcome had ostensibly been decided. As he approached the scorer’s table, he’d look into the stands, and notice the groups from Baltimore filing up the steps and heading out of the arena.

“That used to hurt me a lot,” Graham said. “I would want to yell out to them and say, ‘Hold up ya’ll! Don’t go yet, I’m gettin’ ready to do it!’”

When given extended playing time against Duke at Cameron Indoor Stadium during the regular season, he led the team while scoring 16 points. Maryland Head Coach Lefty Driesell inserted him into the starting lineup during the ACC Tournament, and Graham willingly obliged with performances that he felt he could have been delivering all season.

After losing to North Carolina State twice during the regular season, the Terrapins defeated the Wolfpack 109-108 in the tournament’s opening round, with Graham scoring 20 points. In the semi-finals against Duke, he grabbed 10 rebounds.

Despite the anguish he felt early on about his lack of playing time, Graham proved by season’s end that he was ready to leave his mark on the college basketball scene.

As a sophomore, he started 29 of the team’s 30 games. He captured the country’s attention during a December game against fourth-ranked N.C. State, where he poured in a school-record 44 points in a mere 25 minutes of action. It is a single-game scoring record that still stands at the University of Maryland.

He connected on 18 of his 26 shots from the field and converted eight of his ten free throws in Maryland’s 124-110 victory. It was a dazzling performance that showcased the full repertoire of his unique scoring arsenal. Had the three-point line been in existence, his point total would have exceeded 50.

He scored in double figures in 22 consecutive games. On Super Bowl Sunday in 1979, as Terry Bradshaw was throwing for four touchdowns and over 300 yards and in the Pittsburgh Steelers 35-31 win over the Dallas Cowboys, Graham was putting on his own show at Cole Field House.

Against #1 ranked Notre Dame, Graham scored 28 points as his freshman teammate Buck Williams snatched 15 rebounds in Maryland’s 67-66 upset victory over a Fighting Irish team that featured future pros Bill Laimbeer, Kelly Tripucka and Orlando Woolridge.

But for the second year in a row, Maryland failed to make the NCAA Tournament. Graham led the team in scoring and was tied with Albert King for second in assists and steals. And yet, his individual success could not outweigh the internal struggles that seemed to be taking a heavier toll on him.

“Things were breaking inside of me,” said Graham. “Some things really started to get to me. That’s when drugs became one of my vices. I couldn’t cope at that time in a healthy, constructive manner. That was the decision I made in trying to cope. I was angry and bitter and felt like nobody really cared about me. By the middle of my sophomore year, I started experimenting with cocaine. That was a bad, bad decision.”

Prior to his junior season, he was told that he would no longer be in the starting lineup, that he would have to come off the bench.

“John Lucas, who was in the NBA at the time, came to talk to me and he informed me about the coaching staff’s decision,” said Graham. “That was something that I couldn’t accept. I fought against that, and they eventually put me back in the starting lineup, but they changed me from my natural shooting guard/small forward position to power forward. That put me in a disadvantageous position to show what I could really do.”

“I played power forward for my last two years because I wanted to play,” he continued. “But changing positions like that, my stock, as far as the NBA was concerned, was being damaged. I felt like nobody was hearing me, like nobody was seeing me. That’s when I became more dependent on drugs. They became a consistent part of my life at that time because I wasn’t really trying to deal with what was going on.”

During his junior season in 1979-80, Maryland looked like a national championship contender. They earned a #2 seed in the NCAA Tournament, but lost Georgetown in the Sweet Sixteen. Graham, despite his increasing drug use, was again among the team leaders in points, rebounds, steals and assists.

As a senior, he led the Terps in assists and steals and was again one of the squad’s top scorers. But the team was blown out by Indiana, 99-64, in the second round of the NCAA’s, ending his college career.

Graham’s contentious relationship with Driesell during his four years at Maryland was no secret. Despite his bitter feelings, which intensified due to his increasing substance abuse issues, he was eager to move on and show what he could do in the pros.

On Tuesday, June 9th, 1981, Ernie Graham was ready to party. The champagne was on ice. It was draft night and he was anxiously awaiting the phone call to inform him where he’d be playing.

Mark Aguirre and Isiah Thomas, the childhood buddies from Chicago, were selected with the top picks by the Mavericks and the Pistons, respectively. His Maryland teammates Buck Williams and Albert King were both selected by the New Jersey Nets with the third and tenth overall pick.

As the draft dragged on, the angrier Graham became. When he was finally selected by the Philadelphia 76’ers in the third round with the 68th overall pick, he grabbed the champagne and threw it out the window.

“I did work in rookie camp, though” said Graham. “It got to the point where they said, ‘Man, get him outta here before he gets hurt.’ When we started training camp, I introduced myself to Dr. J, and he playfully slapped my hand away and said, ‘I know who you are. Tell me this, why didn’t you come out of Maryland two years ago?’ He was playfully telling me, ‘Boy, you shoulda been here already.”

Graham played well enough at training camp to secure a roster spot as a reserve, despite the fact that Philly was loaded with talent and would advance to the NBA Finals that year. But despite his talent, Graham’s drug use was no secret. He was the last player released before the regular season started.

“That was the first time I’d ever been cut,” said Graham. “All my chips were on the table in Philly. When they told me that I had to check out of the hotel, and when it hit me that I didn’t have no more meal money coming my way, I realized that I was homeless. All of a sudden, I’d gone from being this basketball star my whole life to being nobody.”

He hid out at a friend’s house for weeks, embarrassed to face the world. He got high even more to escape the disappointment and pain. He avoided his family.

“I had dreams of doing something for my mom, of making my family proud of me,” said Graham. “I’d wanted to buy her a nice house and get them out of a neighborhood that I had once been so afraid to live in as a kid. I had the same dreams, thinking about all those things that playing pro sports can bring, that every poor black kid has coming out of the hood.”

Graham was soon suiting up for the Lancaster Lightning in the Continental Basketball Association. He played his usual brand of ball, accumulating points, assists, rebounds and steals, but his resentments and drug use were impediments to his NBA dreams.

“I could play, everybody knew that,” said Graham. “But I was so angry. My drug use escalated. I had a young son, Ernie, Jr., and I was getting paid peanuts, $250 a week. I went overseas, where the money was a lot better, but the team and the CBA forced me to come back.”

The league would not release him from his contract, thus disallowing him to gain the required license that he needed to play pro ball in Europe. He returned to the U.S., was traded to the Rochester Zeniths and finished out the season.

“I was so bitter at the time,” said Graham. “I was scoring like I normally did. No matter where I played, I was gonna get buckets. But I just didn’t care anymore. I wouldn’t listen to the coach or run the plays that he wanted me to run. I just finished out that contract and then went overseas.”

Graham started out in Spain, where he was paid very well, along with receiving a nice house and car as part of his contract. NBA scouts continued to keep an eye on him, and the Indiana Pacers signed him to a deal on August 1st, 1984.

But his undeniable talent again proved to not be enough. One day during training camp, head coach Jack Ramsey assigned him to guard the Pacers’ 7-foot-4 rookie center, Rik Smits. In the middle of the scrimmage, Graham stormed off the court, yelling at Ramsey, ‘Man, you got to be crazy. You got me playing against this 7-foot-4 dude. I ain’t no damn center, I’m a guard! You ain’t really tryna see how I play. F*** you, I’m gone.’”

(Indiana's Rik Smits. Photo Credit: solarsportsdesk)

“Go on and get outta here,” Ramsey yelled back. “You’ll never play in the NBA!”

“Yeah, I’ll never play center in the damn NBA, I know that,” Graham responded.

The Pacers waived him on October 20th.

Graham knew, from that point forward, that he’d be blacklisted from the NBA. He was resigned to the fact that he’d have to finish out his career in Europe. But Red Auerbach, Boston’s legendary former coach and General Manager, took a final chance on him in 1986 after he averaged 49 points per game in the ultra-competitive Urban Coalition Pro-Am summer league in Washington, D.C.

“Red flew me up to Boston when he flew Len Bias up there,” said Graham. “Lenny was my young boy when he was in high school, when I was playing at Maryland. I got to Boston and Red and I had a good talk. He told me that he believed in my talent. We talked about all of the frustration I had going on inside of me and he told me that in order to have one last shot, I had to let all of that stuff go. But I was drugged out of my mind.”

An opportunity never materialized in Boston. Graham went back overseas and played until 1995. But underneath the surface, away from the high-scoring games, he was steadily destroying himself.

Drug Dealers in Baltimore, and on a few other continents as well, were angrily in search of him due to unpaid debts. He estimates that, over the course of his career, that he easily spent over a million dollars on narcotics. He stole from anyone and was a constant presence at pawn shops. His daily life was a nightmare of pain made worse by the sinister and debilitating crack, cocaine and heroin that coursed through his veins.

“Even though he was doing all that stuff, when we saw him in Baltimore, he would tell us to stay away from drugs and the things that took him off his path,” said Bogues. “He would tell me and Reggie Williams and all of the other young guys, ‘Don’t do what I do. Keep on the straight path and do what you’re supposed to do.’ He saw our basketball talent and knew that we had a chance to go places in life.”

“He would tell us to do everything the right way, that basketball could be a big opportunity for us,” Bogues continued. “He told us about all of his regrets and he helped us to avoid some bad choices. Ernie has always been a guy that had a big heart that looked out for us younger guys, even when he was going through his struggles. He made us aware of the things that we needed to stay away from.”

“I’d been locked up in Baltimore and about five other countries on drug stuff,” said Graham. “It’s amazing that I managed to play pro ball at all, let alone for 13 years. My addiction grew worse over the years. I prayed to God to take my life. I wasn’t going to kill myself, but I was crazy. I was just done. Emotionally, physically, spiritually, financially and mentally, in every way possible, I was bankrupt.”

In august of 1995, he looked at his wife, Karen, and his three-year-old son, Jonathan. The pain and shame was overwhelming.

“He was just such a special kid, I just knew that I had to do better,” said Graham. “I didn’t want to hurt my baby. And my wife stuck by me through everything. There were a lot of times that she wanted to leave. But I guess God intervened, and I’m so thankful that she hung in there.”

Graham voluntarily placed himself in a treatment program, which he successfully completed. But when he returned home, determined to change his ways, his past caught up with him. As he walked outside of his home to drop Jonathan off at the school bus, he was approached by the police.

“They told me, ‘You gotta come with us,’” said Graham. “I’d gotten arrested earlier that summer. I was supposed to go to court for that but never showed up. There was a bench warrant out for me.”

The police drove him to the Washington, D.C. suburb of Upper Marlboro, not far from the University of Maryland’s campus.

“I had on shackles and cuffs, and they had me walking down Route 1 in the middle of the day,” said Graham. “That did something to me, the utter shame, knowing that a mile or so down the street, on Maryland’s campus, is where I put in all that work. As I was walking, in those shackles and handcuffs, I kept asking myself, ‘And this is what it’s all come to?”

“The judge said that he was going to give me time served,” he continued. “But he was very stern and very clear. He told me, ‘Mr. Graham, do something with your life. Because the next time you appear in this courtroom, you are going to prison.’ At that point, I had been clean for 25 days. I told him, ‘Your Honor, today I’m gonna do what I’m supposed to do.’”

After a few more weeks, Graham started feeling like a human being again. He felt that his wife and family deserved more from him. He thought about Ernie, Jr., who he hadn’t spent much time with, and young Jonathan, who he was determined to be a real father to.

“I started thinking about how I could clean up this mess that I’d made out of my life,” said Graham. “I was 36 years old, couldn’t play ball anymore and I had to figure out how to live. After 22 years of neglect, I had to face reality and start piecing my life back together again.”

He’d lost his driver’s license years before, but had previously driven, regardless. Once he got sober, he stopped driving until he could get his license back. He was determined to do things the right way. He applied for jobs, but no one would hire him. So he began walking around for miles with his lawn mower, asking people if they needed their grass cut.

“I had to start somewhere,” said Graham. “My wife had always worked and now that I was home, I had to do my part to help provide for my family. I had to figure out how to put in an honest day’s labor and pay bills. Some days I got work cutting grass and some days I didn’t. It was very humbling.”

After a blizzard that next winter, Graham walked outside in over two feet of snow. As he glanced behind him, he saw his three-year-old son Jonathan, following in the deep imprints of his steps.

“When I saw him stepping in my footsteps, that did something to me,” said Graham. “I said, ‘Man, I gotta walk right from here on out.”

After about six months, he was hired as a counselor, working with mentally and behaviorally challenged youth. His pay was $6.75 an hour. But on his second day on the job, he was assaulted.

“This big heavy kid attacked me,” said Graham. “I grabbed him and tried to restrain him and we fell. I had to have five surgeries over the course of five years as a result of that. I was in a cast from my hip to my foot for 30 days. I couldn’t understand how I could play ball my whole life and never get hurt, and then I go and take a regular job, and this happens.”

As he recuperated, he had an epiphany. He wanted to give back to society and find a way that he could make a decent living, while also expressing his appreciation for getting off of drugs.

“I didn’t want to see anybody else go through what I went through,” said Graham. “I didn’t want anyone else to waste their lives the way I had. I felt like I had to do something to help others.”

He started a non-profit organization called ‘Get The Message.’ He pounded the pavement with the same zeal that once propelled him to chase his high. He secured grant money, along with donations from Orioles legend Cal Ripken, Jr., Ravens owner Steve Bisciotti and corporations like Comcast. He shared his vision and earnestly and effectively communicated his past pain and suffering. He pleaded for help with funding. Baltimore County provided matching grants for some of the money he raised.

‘Get The Message’ established after-school programs and support services for Baltimore area youth. Graham was invited to lecture on college campuses and public elementary schools alike, to share his inspiring story. He saved his money after expenses were paid out and purchased residential real estate.

From 2006-2010, when his youngest son Jonathan starred as a 6-foot-8 forward at Calvert Hall, the elite private school that also produced Terrapins great Juan Dixon, Graham was front row for every game. Jonathan was a two-time All-Metro selection who finished his prep career as Calvert Hall’s second all-time leading scorer.

Today, in addition to his real estate holdings, Ernie owns a restaurant, named Baltimore Basketball Legends. It sits on a stretch of Greenmount Avenue that he was once afraid of, in his old neighborhood that he once saw burned to the ground in the 1968 riots.

In 2009, he had to shut down his non-profit organization, due to dwindling funding sources. Today, in addition to his many speaking engagements, he also does work with the Cal Ripken, Sr. foundation.

“Things were going really well with the foundation, but when the market crashed, there were big cutbacks on funding for after-school programs,” said Graham. “That put a serious damper on what we were doing because it was difficult to get any more matching grants.”

Graham still speaks to thousands of young people every year, warning them about the consequences of their decisions and the people that they hang around. He stresses how important it is to be mindful that one decision can change everything, for the better or the worse. He talks about how difficult it is to get back on the right path once you’ve fallen off.

He talks about the death of his friend Len Bias, and his former Maryland teammate Jo Jo Hunter, who was recently released after a 15 year prison term. He also talks about his basketball accomplishments and regrets.

“If Ernie had never touched drugs, I think he could have gone down as one of the 50 greatest to ever play,” said Wade. “But I’m very proud of him because of the way that he shares his downfall with the youth, how he uses himself as a prime example of what not to do. His message resonates with those kids. He’s helping people turn their lives around. He’s not only a great role model, but I’m also proud of the fact that he has become a tremendous father and husband.”

“The sky could have been the limit for Ernie in terms of the NBA,” said Bogues. “His talent was that special. I’ve always respected him. I look up to him today in the same way that I did when I was a youngster.”

“Ernie was ahead of his time as a basketball player,” said Lewis. “He could do everything. If the drugs never got a hold of him, he would have been a special player in the NBA. But he’s grown and come through a lot and he’s making a difference in a lot of lives today.”

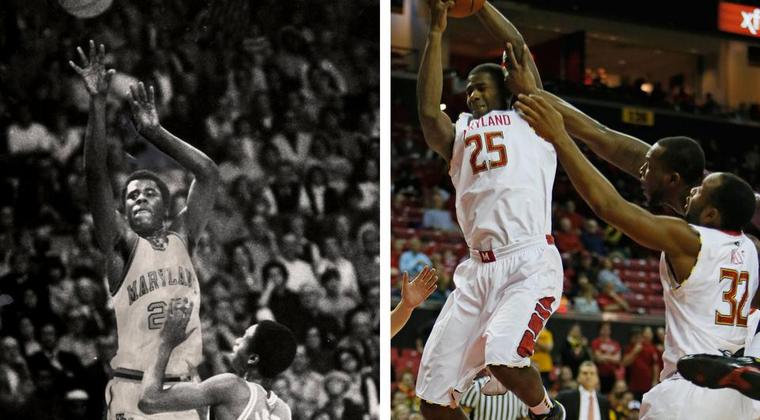

This upcoming season, Graham will be a fixture at the Comcast Center. He’ll be cheering for another Graham who wears #25, his son Jonathan, who transferred to Maryland after spending his first three years at Penn State.

(Ernie and Jonathan Graham. Photo Credit: baltimoresun.com)

“Seeing my son wear my number, #25, for Maryland is an amazing step on this journey,” said Graham. “I’ve been able to reconcile my experiences at Maryland and repair my relationship with Lefty Driesell. I can take responsibility for the things that I did wrong today. And to see Jonathan out there on that court, I’m so happy for him because when he was younger, he always said that he wanted to play there. He also said he wanted to see my number in the rafters.”

Ernie Graham is 55 years old today. This summer, he’ll celebrate 19 years of sobriety. He’s thinking about finishing up the final credits he needs to earn his Bachelor’s degree. He’s also considering a move to get into coaching or scouting on the pro and college level.

“I’m excited to see what the next chapter of my life is all about,” said Graham. “I would love to be around the game of basketball in some capacity. My son has one more year left at Maryland. I’m gonna sit real close and be into every one of Maryland’s games this year. I’m going to really enjoy it. After that, I have to find a new place to go.”