This is Part II of The Shadow League's feature story on former Boston College basketball player Ernie Cobb. If you missed Part I, you can read it here.

COLLEGE LIFE

When he arrived on campus in Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts, Cobb’s internal mantra was, ‘I gotta stay eligible.’ With those persistent affirmations dancing through his mind, he took his academic responsibilities seriously from day one. He was determined to prove that he could do the work, which would enable him to further chase his athletic dreams.

As he walked across the scenic campus, marveled at the school’s architectural splendor or ate until his heart’s content in the dining hall, he’d often pause to quietly give thanks for his fortunate circumstances.

“Being at Boston College, when I first got there, was so amazing,” said Cobb. “It was like a paradise to me, coming from where I came from. The campus was so beautiful. I had my own place to live and all the food I wanted to eat. I had everything I could have possibly asked for. Just by being there, I’d already reached success beyond my wildest dreams. I was so thankful, and was willing to work as hard as I possibly could, both in my studies, and in basketball, to be able to get the most I could out of the experience.”

His girlfriend, whom he’d met during his first week on campus, was an upperclassman that knew how to navigate the school’s academic landscape.

“She knew the terrain in terms of what I needed to be doing,” said Cobb. “She helped tutor me, and encouraged me through some rough spots. There were times when the work got really hard, when I wanted to give up, when I had to stay up all night reading or studying or writing papers, and she’d be right there pushing me, telling me, ‘You can’t give up! You realize that you can’t play if you don’t do this. C’mon, you can do it.’ She was a remarkable individual that helped me so much, in terms of establishing the study and work habits that allowed me to be successful in the classroom.”

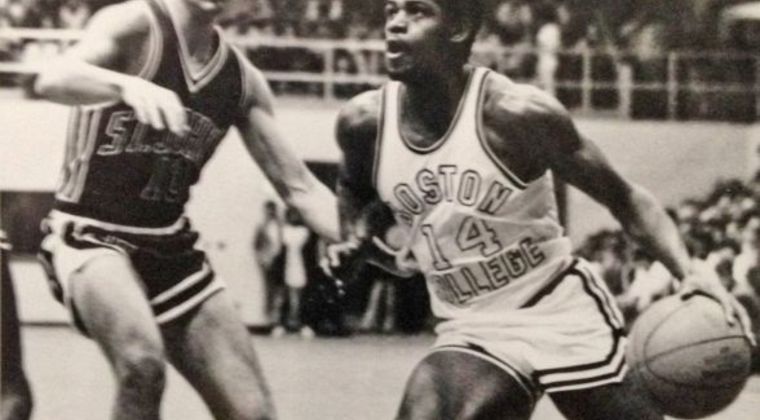

As a freshman, he played sparingly and averaged 4.5 points per game while the Eagles finished with a disappointing 9-17 overall record. But by his sophomore year, when he was inserted into the starting lineup, it was apparent that the 5-foot-11 scorer brought a dimension to the Boston College squad that it sorely needed when he averaged 17.4 points per game.

After his junior campaign, where he converted 52% of his shots, an inordinate number for a small perimeter shooter, and averaged 22.8 points per game, he was recognized as one of the most lethal scorers in the country.

“By my junior year, it was show-time,” said Cobb. “I was having a lot of success, we were turning around the fortunes of the program and I was getting a lot of press in the Boston Globe and area newspapers. They were touting me as the next sub-6-footer to have an impact in the NBA. I was doing well academically and the dream of playing professional basketball was getting closer.”

When he first stepped on the hallowed parquet floor at the legendary Boston Garden, where B.C. would play a few games each year, Cobb was awash with emotions.

“Man, I would watch Jo Jo White, Dave Cowens and John Havlicek playing on television, on that same famous floor where Bill Russell and Bob Cousy and all of those great Celtics teams won all those championships,” said Cobb. “And now, here I was on that same floor, pumped sky high, giving my defender buckets! It was one of the most tremendous feelings I’d ever experienced.”

In practice, he was the lunatic who his teammates sucked their teeth and rolled their eyes at when he told the coaches that they needed to run more sprints after an exhausting practice.

“I took every single practice and every single game seriously,” said Cobb. “We were looking good as a team and my goal was to be the best player I could possibly be. I was focused in the moment. I was relishing that moment. It was all so positive.”

Heading into his senior season in 1978-1979, as the team captain, Cobb was hoping that he could lead his team to the NCAA Tournament. He dreamed of walking away from Boston College at season’s end as one of the school’s most revered sons before embarking on what he hoped would be an accomplished, financially rewarding career in the NBA.

“I was a senior in high school when Ernie Cobb was a senior at Boston College and I’d heard that he was a very good player,” said Lemuel Mills, a Boston area hoops aficionado, coach, community mentor and historian. “It wasn’t until I actually saw him play that I realized how special he was as an offensive talent. He really set the tone in terms of being a strong, dynamic, willful player that wondrous talents like John Bagley, Michael Adams and Dana Barros, all of whom went on to play ball in the NBA after their careers at B.C., followed. All of those guys walked in his footsteps.”

“He was the African-American guard in the modern era of B.C. hoops that blazed a trail,” Mills continued. “He made other African-American ballers feel like they could go there and really showcase what they could do on a national level. And he also cultivated interest, in the area's black community, in terms of being engaged and intrigued by what was going on with Boston College’s basketball program. We weren’t really checking for B.C. like that until he got there. And as black kids who loved ball in Boston, he represented something for us, giving the younger generation something to aspire to in terms of their basketball skills because he was putting in some serious work.”

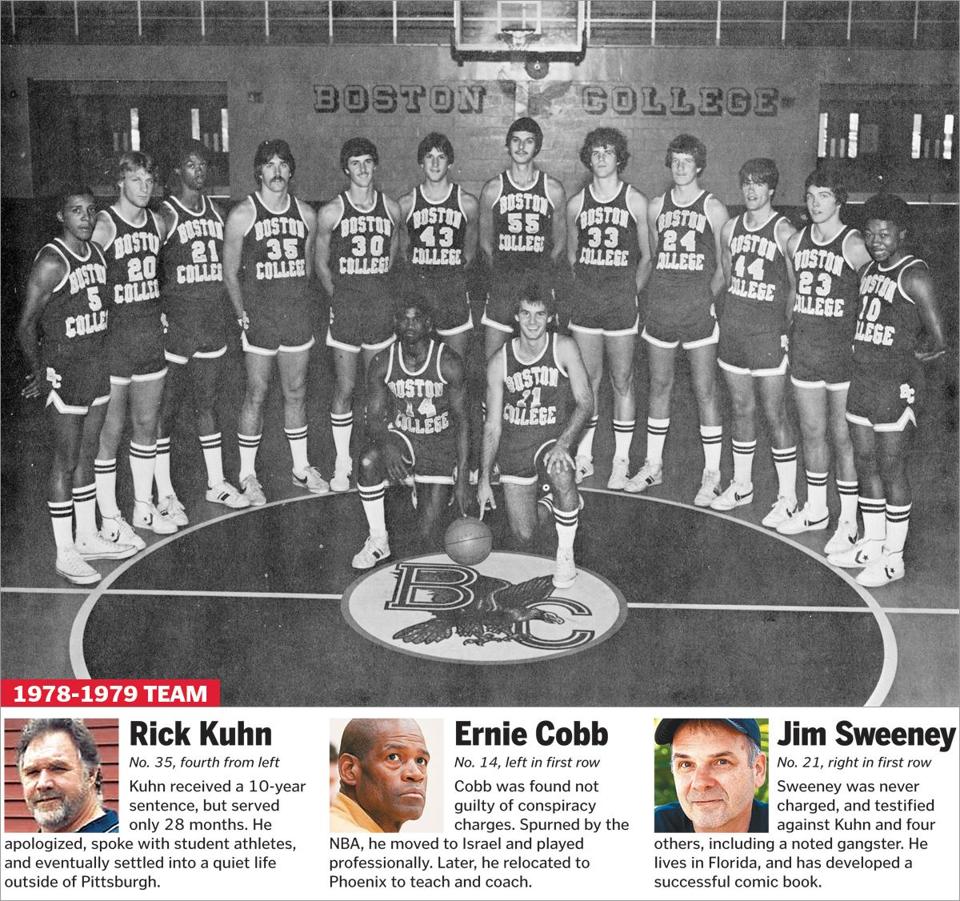

Early on, before the season got underway, Cobb says that he was approached by a man from Pittsburgh named Rocco Perla, who he’d seen hanging around campus with his teammate, senior forward Rick Kuhn. Perla and Kuhn had gone to high school together and were good friends.

“Rocco comes up to me and says, ‘Hey, sometimes I bet on games and I wanna know how you think you guys are gonna do against Stonehill and Bentley?’” said Cobb. “I told him, ‘I think we’re gonna blow them out, we look really good. It’s gonna be no contest. They’re no match for us.’ He told me, ‘Well good, I plan on betting on those games and if you guys win and it turns out like that, I’ll take care of you.’”

“Man, I was one of the most recognizable athletes on campus and people would come up and talk to me all the time, people I didn’t know,” Cobb continued. “I thought he might have been a student, because he was young and I saw him hanging around Rick Kuhn all the time. I didn’t think anything of it. I was like, ‘Yeah, whatever.’ Sure enough, a few weeks later, he hands my girlfriend an envelope. We get home, I open it up, and there’s $1,000 in there.”

THE SCHEME

In the summer of 1978, Rocco Perla and his older brother Anthony, back in Pittsburgh, were the ones who initially conceived the point-shaving scheme that would later rock the college basketball world. With Rocco’s high school buddy Rick Kuhn entering his senior year at Boston College, where he was expected to be a contributor to the school’s basketball team, the brothers figured they could make a ton of money. All Kuhn had to do was ensure that the Eagles fell short of the point spread in the games that they bet on.

So, in very basic terms, if B.C. was favored to win a game by ten points, Kuhn had to make sure, if the game was in play with the mobsters and the bookies, that they won by less than ten in order for the gamblers to make money.

But Kuhn was a player of limited ability, so he recruited his roommate and best friend, who also happened to be the most important player on the floor, the team’s senior point guard, Jim Sweeney.

(Rick Kuhn, Photo Credit: bostonglobe.com)

The abbreviated version of events reads like this: the Perla’s brought in a Pittsburgh hood named Paul Mazzei, who contacted his friend Henry Hill, an associate of New York’s Lucchese crime family that had befriended him during a stretch in federal prison. Hill brought in his mentor, Jimmy Burke, to finance the operation and set up a network of bookies who could advance the financial potential of the scheme.

Hill flew into Boston, at the behest of Jimmy Burke, late in 1978 to meet with Mazzei, the Perla’s, Kuhn and Sweeney at the Logan Airport Hilton and ensure that everything was in place.

Burke’s gang had just successfully pulled off the Lufthansa airport heist at New York’s JFK airport, where they’d stolen an estimated $5 million in cash and $875,000 in jewels, the largest cash robbery in America at the time. The characters and events were later immortalized by the actors Ray Liotta and Robert DeNiro in the classic film, Goodfellas.

The scheme was hit or miss early on. Sometimes, B.C. won the gangsters some serious money by falling short of the spread. Other times, they didn’t deliver as promised, which caused some very dangerous and ill-tempered men to lose large sums of cash. When Henry Hill started threatening Kuhn and Sweeney, promising that they couldn’t play with broken limbs, the players, according to Hill, claimed that they were doing their best, but the scheme would never work unless Ernie Cobb was in on the fix.

“Of course, the damn players had a million excuses,” Henry Hill wrote in Sports Illustrated’s bombshell story, How I Put The Fix In, which was the magazine’s cover story on February 16th, 1981. “But what was I going to do, take it to court?…It was here that they began telling Perla we would have to have Cobb. They said they were trying like hell but they couldn’t get the job done because Cobb was the key man on the team.”

After Boston College beat Holy Cross 89-87 in the first game between the two schools that season, Hill said in SI, “Well, B.C. won by only two points and I had a lot of losing money down on this game. It wasn’t an absolute disaster but it was a cousin. The problem was Cobb. He just kept swishing them in, 30 or 35 points, I don’t remember.”

Hill went on to say, “And they (Kuhn and Sweeney) were still saying, ‘We got to have Cobb.’ I realized that and so I passed the word through Tony (Perla), ‘At all costs, talk to him.’ Next thing I heard Cobb was all set, but it was going to take another $2,500 for his share. Of course, of course I was upset, but what could I do? I didn’t like dealing with a third party I didn’t know and had never met…But the word came back that Cobb was enthusiastic and, don’t worry Henry, nothing can screw up now.”

“In the 30-for-30 documentary that ESPN just aired, Henry Hill admits that he never talked to me,” said Cobb. “Rocco and Tony Perla were giving money to Rick Kuhn. Jim Sweeney admits that Kuhn gave him cash. And in that article in Sports Illustrated, Henry Hill says, ‘The word came back that Cobb was enthusiastic.’ The key phrase there is ‘The word came back.’ I don’t know what Rick Kuhn was telling Henry Hill or the Perla brothers. For all I know, he told them I was in, that it would cost an extra $2,500 per game and he was trying to hustle the gangsters while pocketing the extra money. I don’t know what went down because I wasn’t involved. All of Henry Hill’s and the Perla brothers’ information was coming from Rick Kuhn, and who knows what he was saying to them to cover his own skin.”

(Jim Sweeney, Photo Credit: tampabay.com)

“Kuhn and Sweeney got in over their heads,” Cobb continued. “I’m going off on the basketball court, scoring like crazy, the gamblers are losing their shirts, and they start talking about, ‘We have to have Cobb.’ Anybody that’s ever seen me play knows that I was only stuck in one gear, and that was super-charged-turbo! I had a relentless type of game.”

THE AFTERMATH

In the 1979 NBA Draft, Magic Johnson was the first overall pick of the Los Angeles Lakers after leading Michigan State University to the National Championship over Larry Bird’s Indiana State team. Other notable players selected in that draft included Sidney Moncrief, Bill Laimbeer, Bill Cartwright, Mark Eaton and Jim Paxson.

Cobb was drafted by the Utah Jazz in the 6th Round and cut during training camp. But by the next summer, in 1980, he sparkled while playing for the New Jersey Nets during the pre-season.

“I saw Ernie score 28 points against the Celtics in one of the final pre-season games when he was with the Nets,” said Alswanger, Cobb’s former high school coach. “We were all so excited for him. They couldn’t stop him. The Nets coaches were telling me, ‘Coach, he’s gonna be a great pro.’”

“I had a great camp with the Nets and was poised to make the team,” said Cobb. “I was eating Rory Sparrow up, who went on to have a decent NBA career, in that camp. I just knew that not only was I going to make the team, but I was going to be a factor in the NBA. I was shining at the camp. My moment had arrived. Everything I’d worked so hard for was coming to fruition.”

After perhaps his greatest moment during the preseason, when he had that outstanding game against the Celtics right before the regular season tipped off, Cobb was relaxing in his hotel room when he heard a knock at the door.

“I opened up the door and it was these guys from the F.B.I.,” said Cobb. “They showed me these pictures of these mafia guys and were asking me, ‘Do you know him? Do you recognize him?’ And my answer every time was, ‘No!’ I didn’t recognize any of those mobsters because I had never met them. I didn’t know what that was all about. They mentioned the $1,000 that Rocco Perla gave my girlfriend and I told them the truth. They left, and that was that. The very next day, the Nets cut me.”

“When the F.B.I. talked to the Nets, their head coach Kevin Loughery called him in and said, ‘You know why I have to let you go,’” said Alswanger. “Ernie, and anybody who truly knew him, who knew about his character and what type of young man he was, we were all heartbroken. It was a tragedy that he never got another chance to play in the NBA.”

“Kevin Loughery never gave me a firm reason why the Nets were letting me go,” said Cobb. “But it wasn’t a coincidence that one day, the F.B.I shows up asking me about gambling, and the next day I’m no longer with the team. Loughery told me that I had the ability to play in the NBA. He told me to keep playing and working hard and that one day I might get another chance.”

When the story first broke in January of 1981, Cobb was in shock. The phone calls flooded in from his friends and family in Boston and Connecticut, with despaired voices on the other end asking, “Did you do this? What’s going on? Were you shaving points for the mob?”

The headlines in Boston, and around the country, said that Cobb and fellow senior Michael Bowie, the team’s two African-American stars, were the players that were implicated.

“Boston College Accused of Point Shaving,” was the big headline on the UPI wire. The story read, in part, as follows:

Ernie Cobb tossed in 1,760 points in a stellar basketball career at Boston College and only two other Eagles scored more.

But it’s the points that Cobb and teammate Michael Bowie didn’t score during the 1978-1979 season which has spawned a federal investigation.

The Boston Globe reported on Friday that Cobb and Bowie are targets of the federal probe into allegations of point-shaving in three Eagles games.

The Globe, quoting an unnamed source in New York, said the three games in which point-shaving was alleged were a Feb.3 game against Fordham, a Feb. 6 game against St. John’s and a March 1 game in the ECAC Regional Playoffs against Connecticut…

The point-shaving allegations surfaced during an unrelated investigation into the 1978 theft of $5.8 million from the Lufthansa cargo terminal at New York’s Kennedy Airport. Boston College confirmed the investigation on Friday.

The Boston Globe story was initially investigated and written by a young Boston College alumnus named Leslie Visser, who would go on to become a very accomplished, groundbreaking journalist and role model for women who aspired to work in the field of sports media. Visser became the NFL’s first female beat writer in 1976, when she was assigned by the paper to cover the New England Patriots.

Bowie’s reputation was immediately sullied and he subsequently lost his job playing pro ball in Europe when the story broke. The Globe would later admit that they were wrong in reporting that Bowie was involved, after he was not implicated nor investigated by the federal government for any role in the scandal. The distinguished paper later retracted the story. But for Bowie, it was too little, too late.

“When the story first broke, it said that Michael Bowie and I were the ones implicated,” said Cobb. “I was like, ‘You gotta be kidding me!’ Jim Sweeney and Rick Kuhn’s names weren’t mentioned anywhere. So I guess the thought process was, ‘Well, if there were criminal activities going on, it had to be the brothers!’ My name and picture, and Michael Bowie’s as well, was on the front page of every newspaper in the country.”

After the investigation was completed, Cobb was not named as a defendant in the initial trial, U.S. vs Burke, which opened to a circus of media attention on October 27th, 1981.

“At that point, I was looking forward to a trial,” said Cobb. “I felt like, ‘You put my name out there, so let me clear my name!’ When they investigated me, I told them straight up about the $1,000 that Rocco Perla had given me. I was forthright and honest with them. I admitted to receiving that money, and spending it. But that had nothing to do with shaving points.”

“At the time, I was naïve,” Cobb continued. “There were a lot of rich kids who went to Boston College. I said, “If this dude has cash like that to burn and wants to give me $1,000 because I told him we’d destroy Stonehill, sure, I’ll take it.’ Maybe he was trying to cultivate a relationship with me and soften me up for something down the road. But I never agreed to fix any games or shave any points. And yeah, I took that money. I never lied about that. My girlfriend and I bought a new stereo, television and some furniture. We had a good old time. And after they put my name out there, and after I admitted to taking that $1,000, they didn’t have enough evidence to prosecute me. So I didn’t even go on trial with Kuhn and the mobsters that put the whole thing in motion.”

After Cobb was not charged, he thought he was finally past the sordid affair. After the four-week trial in 1981, Jimmy Burke was sentenced to 20 years in prison, while Paul Mazzei and Tony Perla were sentenced to ten. Rocco Perla received a four-year sentence and Rick Kuhn was sentenced to a ten-year bid as well, which was later reduced to 28 months. Jim Sweeney was not charged.

With his name swirling down the vortex of the mob cesspool from the moment the story broke, Ernie Cobb found it difficult to make a living.

He sold copy machines and paved driveways for an asphalt company, which was ironically the same job his father found when he’d relocated from North Carolina to Connecticut some twenty years earlier. He tried to subsist as a substitute teacher, and even caddied at the Fairview Country Club in Greenwich, Connecticut, the affluent suburbs where he’d previously been arrested for stealing bikes as a kid.

He took advantage of an opportunity that surfaced when a pro team from Israel offered him a spot on their roster. He quickly thrived and was recognized as one of the league’s best players. He was hopeful that he’d have another chance to make it in the NBA.

“I was back at home, visiting for the summer and about to return to Israel,” Cobb said. “I’d led the pro league in scoring over there and signed a very nice contract. I loved it in Israel, the fans loved me and the people were so beautiful. They treated me great. But I found out that I wouldn’t be allowed to leave the United States because the government was going to bring me to trial.”

On June 23rd, 1983, more than four years after he’d played his final game at Boston College, Ernie Cobb was indicted and charged with taking cash bribes to alter the outcomes of games against Harvard, Rhode Island and Fordham.

When he told Alswanger about the indictment, his old high school coach spoke sternly with him, as he'd done some twelve years earlier when Cobb had just returned home from the juvenile detention facility.

“Ernie, don’t lie to me,” Alswanger instructed him. “Tell me what you did and what you didn’t do. You understand? You gotta tell me the truth, because I gotta know how to go on this?”

Convinced that Cobb was innocent after his mentee walked him through everything that had transpired, and certain that he was being used by the federal government to send more organized crime figures to prison, Alswanger began working the phones.

“I called my buddy Frank Melzer, who was an attorney,” said Alswanger. “He wasn’t a trial lawyer, so he brought in his colleague, David Golub. Golub was a brilliant lawyer, and he told me that he’d have to interview Ernie first to see if he was gonna take the case on. After he interviewed him, he fell in love with him and told me, ‘He’s innocent. I feel it.’”

A fitness fanatic who augmented his training by swimming and riding his bicycle very long distances, Cobb hopped on his ten-speed shortly after the indictment was announced and began pedaling.

“They’d taken my passport and I had to stay here and face these charges,” said Cobb. “I was so frustrated at one point that I got on my bike in Stamford, Connecticut and just started riding. Fourteen hours later, I arrived in Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts.”

A few blocks from Boston College, the place that held so much meaning to him, where he’d worked so hard to create his life’s purpose, the symbolism was inescapable when he found that he had a flat tire.

“I hadn’t seen Ernie for several years,” Jack Hennessey, a psychologist at Boston College that had served as an informal academic advisor during Cobb’s days as a student, told the New York Times in April of 1984. “He stopped in my office with his bike with the flat tire and borrowed $20 to get it fixed and to get home. He’s a good person. He worked hard in class. He graduated on time with a degree in sociology. When he was implicated in the scandal, I was shocked.”

On the stand during the trial, Rick Kuhn’s girlfriend, Barbara Reed, with whom he shared an apartment during his senior year at Boston College, testified that she overheard Kuhn and Sweeney discussing the Fordham game, saying that they had to keep the ball away from Cobb because he shot the ball all the time. She also recalled Kuhn saying that Cobb was “too into his own game” to cooperate with “the betting thing”, but the New York gangsters were adamant about getting him involved.

At the close of the two-week trial, Alswanger was the last character witness who took the stand in Cobb’s behalf. When he finished with his testimony, he made a beeline straight for the restroom.

“I walk in the bathroom, and who was in there but Peter Vario, the big-time mobster that was on trial with Ernie,” said Alswanger. “I was nervous because I didn’t know what was going to happen. He turned to me and said, ‘Coach, I’m glad you’re sticking up for your kid. He’s innocent.’”

“When they indicted me, they wanted Peter Vario, the mobster, so they tried us together,” said Cobb. “When the evidence came up at the first trial, it didn’t match up, but they still came after me a few years later. I was this poor kid with no financial resources, going on trial with a member of the mob. But my high school coach got his friends to take my case, pro bono. It had to cost around $200,000 at the time to defend me.”

On Friday morning, March 23rd, the jury came back with a unanimous innocent verdict for Ernie Cobb, exonerating him of all charges. He jumped in the air, as if soaring for a rebound, as cheers filled the courtroom. He hugged his tearful mother before walking out into the hallway for a few moments.

“I just had to be alone,” Cobb told the reporters afterwards. “This has gone on for four years. My family has suffered. I have suffered. My parents have suffered. I don’t know if the losses can ever be made up…not the losses me and my family and friends have suffered. But I don’t feel any bitterness toward the prosecution. They were just doing their jobs. I just thank God there is justice.”

NO CLOSURE

But for many, there is a fierce bitterness that still lingers to this day.

“Henry Hill avoided going to prison, and he went off into the sunset of the government’s Witness Protection Program,” said Alswanger. “He killed people. He was a murderer and a horrible human being. And look what he did to the lives of those kids. The other two kids made whatever choices they made, but look what was done to Ernie. His life’s dream of making it to the NBA, which was where he belonged, was taken away from him. But I’m so proud of him because he picked his life back up and made the best of it. That’s the real strength of his story, that you pick yourself up and make something of yourself.”

Today, Cobb’s relationship with Boston College remains strained.

“Out of everything that happened, that’s one thing that hurts me tremendously,” Cobb said. “I don’t know if they recognize it, but B.C. and I were the victims of the same circumstances that were beyond our control. I’m not angry at the school. I understand that they want to disassociate themselves from the scandal. I want to be disassociated from it as well. The fact that I went to court and fought for my name, that I stood up for myself and cleared my name, that I was exonerated and acquitted, it’s a travesty that I’m still associated with this.”

“My name is indelibly linked to it,” Cobb continued. “I’m stuck. I continue to feel like I have to defend myself, all these years later, even after the government tried their case against me and I was found innocent. I feel like I did all that fighting after I lost my dream of playing in the NBA, and it was all in vain. But I know that it’s not really in vain, because I know the truth.”

POST-SCRIPT

Ernie Cobb played professional basketball in Israel for 17 years, where he learned to speak fluent Hebrew. He traveled throughout the world, getting paid to play the game that he loved.

When he returned to the United States, he moved to Phoenix, Arizona, where he became a Special Education teacher and high school basketball coach. He recently earned his Master’s Degree in Education and is currently considering pursuing a Ph.D.

“I feel like I’ve led a remarkable life,” he said. “When I think about my journey, it brings tears to my eyes. I never got to realize my dream of playing in the NBA, but I’ve been all over the globe and have experienced so many different and beautiful cultures. I have an incredible circle of supportive friends and have met some amazing people who have impacted my life in ways that I can’t even begin to describe.”

“Mr. Alswanger, my high school coach inspired me to rise above my circumstances,” he continued. “That’s why I got into education and coaching. I feel like if I can change one life, like he changed mine, man, it makes everything I’ve been through worthwhile.”