2016 has been the blackest year in television and film that we’ve had since Sweet Sweetback spent nearly 90 minutes on the run.

Two of my personal favorites have been FX’s Atlanta and the recently released screen adaptation of the play Fences. Both take an insider’s view of black life, the everyday, the mundane, the hilarious, and the painful outside of the white gaze.

In Fences there are no white characters. In Atlanta, the few white characters are peripheral characters used for comedic fallout. The storyline is based on the culture of black lives lived in black spaces and in so doing, there are inside jokes that most white people won’t get.

In Atlanta’s first episode, there are subtle jokes between Earn and his parents. There’s Darius’s esoteric humor. And then theres the white radio deejay who Earn plays for thinking they are so cool with one another that he can say n****a comfortably in front of him, showing him that he’s not the kind of black person you can say n****a in front of anymore than his much more physically intimidating cousin Paper Boi is.

In fact, there’s no black person a white person should feel comfortable saying n****a in front of, because, well, you can’t. So, there’s that.

There are plenty of laugh out loud and creative, out-of-the-box moments in Atlanta, including a fight in a parking lot ending with patrons getting hit by an invisible car, an entire episode devoted to a talk show with original commercials, a conversation about the various flavors of sunflower seeds, (including sushi flavored), and a lemon pepper chicken wing moment.

Fences is a far more serious take on the false romanticism of close-knit families and working class life as honorable and heroic. But even within the seriousness of Troy both realizing his family is the best thing that has happened to him and being bitter that better things couldn’t have happened to him because of the color of his skin, he still is able to exhibit joy.

He laughs with his friends, looks out for his brother injured in the war, and tells whoever will listen that he loves to make love to his wife.

In these two slices of black life in Atlanta and Fences, there is more than lemons and lemonade, there’s a cultural wink and a nod to a shared understanding that cultural norms precede any kind of struggle. We have survived because of a culture that says music and dance is an everyday part of life.

That laughter soothes.

That love means you take in your brother with the metal plate in his head.

That, like the parking lot “attendant” said in Atlanta, “we all we got!”

Despite the struggle, Troy is still going to tell stories with his friends and Earn is still going to tease his girl and love his daughter, theorize with Darius and smoke weed with Paper Boi.

Both Fences and Atlanta show what the limits of black opportunity and the bravado to dream does to people, particularly to black manhood, even though they are set in different time periods.

In Atlanta, we learn that Earn (Donald Glover), who comes from humble roots, had a potentially promising future as a Princeton University student, but left for reasons unknown.

Being smart when you’re black isn’t enough to make it back into your parent’s house as Earn struggles in a minimum wage job at the airport. His dream is to make it in the music industry, a dream the mother of his daughter views as a luxury as she bears much of the financial burden of caring for their baby.

By the end of the first season, Earn is beginning to see the rewards of his dream and handing over all of his money to his woman, while living in a storage bin. He wants to do the right thing by his family and fulfill his dreams.

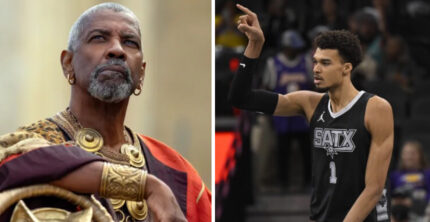

In Fences, Troy Maxson (Denzel Washington) has been promoted as a driver of a garbage truck and hands over his pay to his wife whenever he gets it. Troy once had a dream and the skills to be a professional baseball player, but was limited before integration allowed for black players in the major leagues.

He’s consumed by this bitterness and this dream deferred, so much so that he visits it upon his own son and destroys his family from the inside out. The kind of joy he could have witnessed by fulfilling his dreams now lies next to him in the form of a woman that’s not his wife.

What both Fences and Atlanta do well is create stars from characters that are not touted as lead characters. There’s been talk of Darius (Keith Stanfield) having a spin-off from Atlanta. His musings alone are worth the watch (If you could use a rat as a phone, thatd be genius. Theres five rats for every one person in New York alone. Everybody would have an affordable phone. It’d be messy…But worth it.)

And Rose (Viola Davis), with her understated patience, even out-Denzeld Denzel’s usual shoe-program-n***a! style, where he completely becomes the character he’s playing. Davis is both physically beautiful and not afraid to do the ugly, snotty cry. The story becomes less about Troy’s dreams deferred when we find out how much Rose has quietly given up for a life that only involves loving her family with nothing left for herself.

This sort of nuance of black life can only be achieved by having black writers in the room and black people at every level in production. This is something that both Glover and Washington insisted on and because of their influence and insistence, were able to pull off.

While, as black audiences, we enjoy seeing authentic representations of black life, this kind of nuance and complexity of characters bodes well for storytelling for all audiences. Here’s hoping the end of 2016 won’t end this trend.