“Hey Mars Blackmon! You suck! Go back to Brooklyn!”

The first time I heard that I smiled. I’ll be the first to admit that in high school (and probably still to this day), I was one of those annoying New Yorkers who told you where I was from at least ten times a day. Especially while playing prep school basketball in New England.

On the basketball court in high school, whenever I made a nice move, I kept things pretty low key. Except for when the dude guarding me was prone to some ill-advised trash talk. Then, he’d be bombarded all game with, “Ayo! I’m from Brooklyn!!! You can’t guard me, son!”

Back then, in the mid to late ’80s, some fans of the opposing teams had very little reference for my home neighborhood. But one person did. After hearing enough of my hubris, he began yelling at me, calling me Mars Blackmon.

And I absolutely loved it. Because my Brooklyn neighbor Spike Lee had sparked something inside of me in 1986 when I first saw his debut film, She’s Gotta Have It.

Spike not only established himself as an emerging voice and force to be reckoned with in the film industry, but there was also an edge in his work that I could relate to, which inspired my own artistic and creative ambitions.

The film was about female sexual freedom and the mystical, enchanting specter of Black female sexuality, as seen through the lens of lead character Nola Darling. But for a 16-year-old kid who lived where the movie was filmed, the Mars Blackmon character, a long-struggling New York Knicks fan like myself, stole the show.

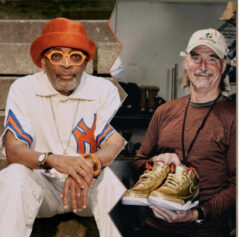

(Photo Credit: indiewire.com)

This was before hipsters euthanized the neighborhood, at the height of the Crack plague that decimated our beloved communities. But Spike’s portrayal of my home was incredibly sincere, despite the film’s rough edges and the filmmaker’s rookie mistakes, because my streets were not only filled with coke, crack, malt liquor and weed. My neighbors included dentists, sanitation men, rappers, cops, jazz musicians, struggling actors, local politicians, artists, bankers and healthy, loving families as well.

There was a depth and hilarious quirkiness to each character that kept She’s Gotta Have It far removed from the stereotypical presentation of blackness that the cinematic power structure arrogantly bombarded us with.

Through Nola’s polyamorous adventures with Mars, Greer Childs and Jamie Overstreet, her confidence and radiance ushers in a new conversation on romantic commitment and a singular pursuit of satisfaction, however one chooses to define that. There’s a frisky exuberance and playfulness that’s encapsulated in Mars refusing to take his Air Jordan’s off during fornication.

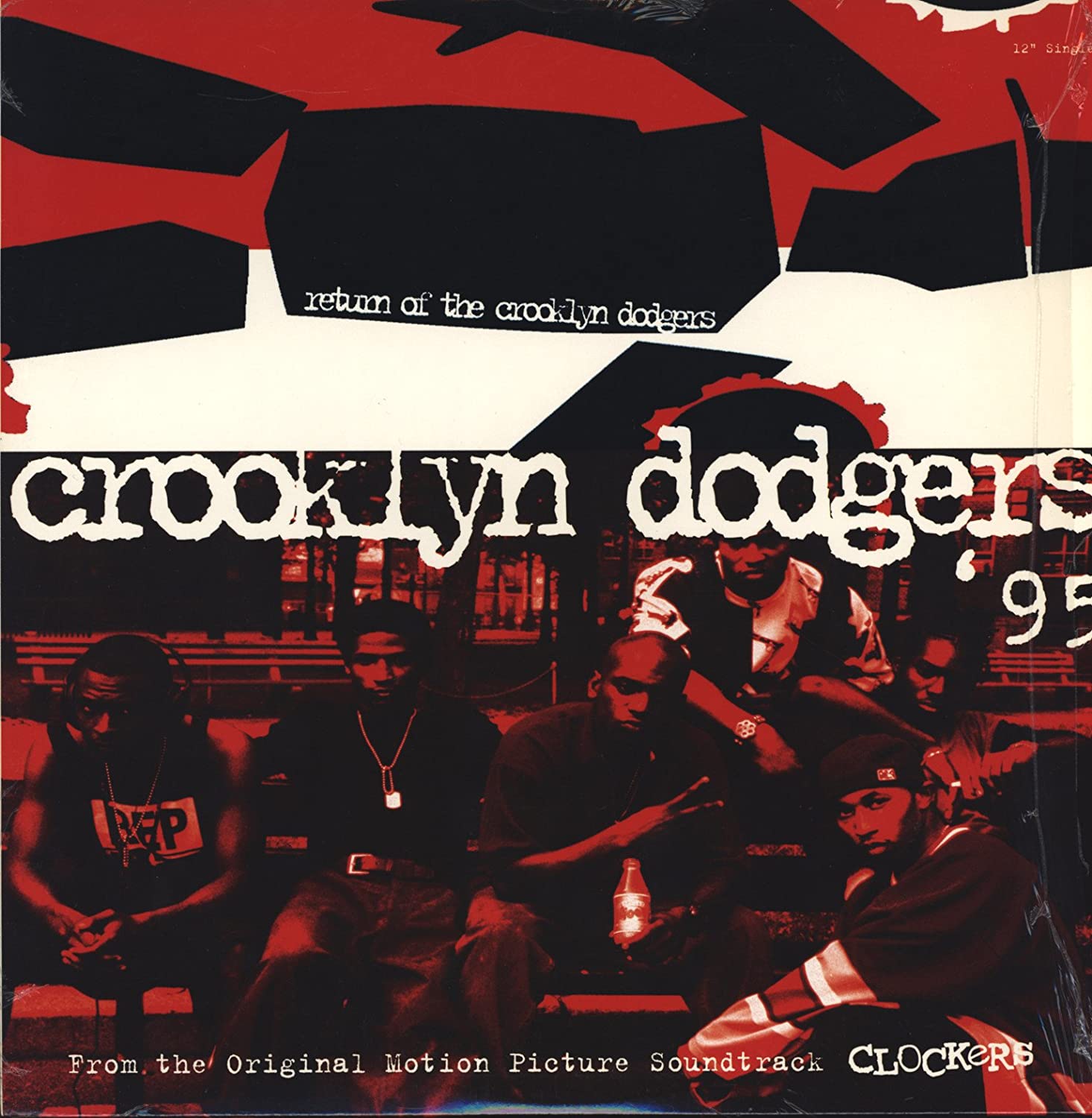

(Photo Credit: sneakerpedia.com)

I remember being captured by the film’s unspoken opening words, the brilliance of Zora Neale Hurston reverberating through time and space with her quote from my favorite book ever, Their Eyes Were Watching God, “Now, women forget all the things they don’t want to remember and remember everything they don’t want to forget. The dream is the truth. Then they act and do things accordingly.”

Nola doesn’t fit into one neat category, which is a perfect parallel for Spike, as we see through the lens of his later prolific work. But as we sit here 34 years later, it’s Mars who still lives on in perpetuity through Spike’s later collaboration with Nike, helping to craft the initial message for the nascent Air Jordan sneaker brand.

People to this day walk around saying, “It’s gotta be the shoes,” knowing nothing of its origin.

The movie was so damn classic and nice that Spike had to do it twice, with his successful 2017 reboot on Netflix.

When I think of She’s Gotta Have It, I think of those taunts from those kids at opposing prep schools up in New England, calling me Mars Blackmon. It still brings a smile to my face.

And on the 34th anniversary of my first look at this wonderful story about this beautiful, confident woman who just had to have it, I still walk away saying, “Please, baby, baby, please,” over and over again.