Quick trivia question – which Division I men’s basketball conference, other than those that oversee the nation’s Historically Black Colleges and Universities like the MEAC and the SWAC, currently has the country’s highest concentration and percentage of African-American head coaches?

Many will be surprised to find that the answer is The Ivy League, where an astounding 50% of the conference’s programs have an African-American roaming the sidelines and occupying the top spot.

Throughout the month of February, in honor of Black History Month, we’ll delve into the lives of Cornell’s Bill Courtney, Harvard’s Tommy Amaker, Yale’s James Jones and Penn’s Jerome Allen, bringing you portraits of who these men are, not simply as hoops coaches, but also as educators and mentors at some of America’s most academically rigorous and prestigious institutions of higher learning, examining how they’ve arrived at this specific juncture in their respective life journey’s.

For those who may not follow college basketball on a consistent basis, there may be a preconceived notion about the quality of hoops being played in The Ivy League. And to debunk that stereotype, which normally centers around athletically inferior Rhodes Scholars utilizing screens and backdoor cuts to lull their competition into a sense of complacency, all you have to do is hearken back to last March.

Tommy Amaker’s Harvard team was making its second consecutive appearance in the NCAA Tournament, yet the program was mainly a topic of national conversation because of the shocking ascendance of Crimson alum Jeremy Lin on the NBA landscape, which became popularly referred to in the public lexicon as the sports and cultural phenomenon known as Linsanity.

But if you saw Harvard defeat a team that many deemed a potential Final Four contender in #3 seed New Mexico, 68-63, in the opening round of March Madness behind Wesley Saunders’ 18 points, Laurent Rivard’s five three-pointers and the crafty floor generalship of freshman point guard Siyani Chambers, you could easily sense that the result was far from a fluke.

Harvard didn’t come into the tournament merely to be a Cinderella Bracket-Buster. They walked in with a legitimate and talented crew, with their bulldog defense, calm demeanor, sublime spacing and crisp ball movement, all of which are hallmarks of a well-drilled and excellently coached team.

If you saw them put the clamps down on New Mexico’s Tony Snell, who now plays for the Chicago Bulls, or bang in the post with the Lobos big men Cameron Bairstow and Alex Kirk, you certainly would have uttered the same thing I did: “Let the Crimsanity begin!”

And if you thought Princeton and Penn’s Final Four runs in 1965 and 1979 were a thing of the past, think again. In 2009-2010, Cornell was one win away from advancing to the Elite Eight. So don’t let the smooth flavor fool you. These future world leaders and titans of industry can play ball.

Although some may be surprised that the Ivy League is on the cutting edge of coaching diversity in its basketball conference, the schools known as “The Ancient Eight” have a long-standing tradition of African-American accomplishments within their athletic programs and being somewhat ahead of the national curve. Have you heard all of this chatter about Russell Wilson, Colin Kaepernick and Cam Newton advancing the cause and holding the flame aloft for those Black quarterbacks that paved a smoother path for them, guys like Donovan McNabb, Steve McNair, Michael Vick, Warren Moon, Randall Cunningham, Doug Williams and on through the early trailblazers like Vince Evans, James Harris and Joe Gilliam?

Well, in 1973, in an era, as Dr. Todd Boyd says in the introduction to his phenomenal book, The Notorious Ph. D’s Guide to the Super Fly ‘70s, “… when Black popular culture exploded in America, a watershed moment when the culture moved from the segregated spaces that it had been forced into, out into the open, now available for a full public viewing,” the Ivy League delivered something that had never been seen before in more than 100 years of major college football.

Back when Fred Williamson’s character, Tommy Gibbs, was running the streets of Harlem in the film Black Caesar, when Pam Grier had the entire male populace stuttering and stammering like the champ in Harlem Nights with her arresting beauty in Coffy, and when Max Julien’s Goldie outmaneuvered Pretty Tony and the Oakland police department in The Mack, when Roberta Flack was killing them softly and Marvin Gaye was getting it on, when the O’Jay’s were riding the love train and Gladys Knight was leaving on a separate midnight train to Georgia, when The Spinners were wondering, “Could It Be I’m Falling in Love” and when Curtis Mayfield’s Superfly soundtrack was the hottest thing in the streets, the Ivy League added another element to this potent mix.

When Penn played Brown at Philadelphia’s Franklin Field on October 6, 1973, led by their respective quarterbacks, Marty Vaughn and Dennis Coleman, it was the first matchup ever between two starting black signal callers in the major college ranks. The outcome of the game is irrelevant, because what they did went beyond football. Playing the most scrutinized position in all of sports, at universities with the highest of academic standards, they deconstructed myths and laid a foundation.

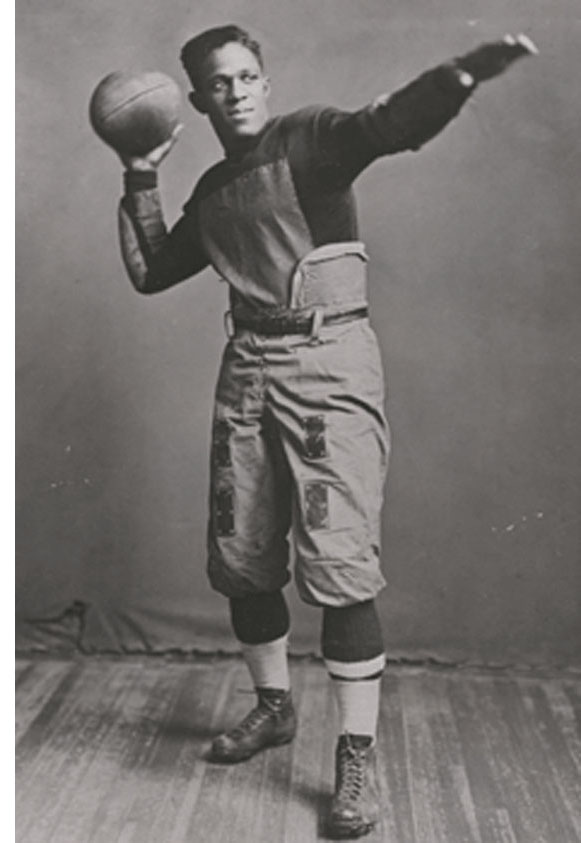

And there were few that laid a foundation quite like a gentleman named Frederick Douglass Pollard, or as he was more popularly known, Fritz Pollard. In 1916, the star halfback and quarterback, and chemistry major, led Brown University to the Rose Bowl, where he was the first African-American to compete in the distinguished bowl game. He later went on to become the first African-American quarterback and head coach in NFL history, and was very much as historically relevant as the great heavyweight boxing champion Jack Johnson or major league baseball’s Jackie Robinson.

And even prior to Fritz Pollard, there was William Henry Lewis. Before he became the first African-American to argue a case before the U.S. Supreme Court alone and win, Lewis was the first African-American to be named an All-American in college football in 1892. He was also Harvard’s first black team captain. While practicing law, he also served as a defensive assistant coach at Harvard, which went 114-15-5 during his twelve-year stint on the coaching staff.

Have you ever heard of a “neutral zone” infraction penalty in a football game? Well, Lewis invented the term and the infraction, both of which remain in use today, to alleviate the severe brutality that took place on the line of scrimmage prior to the snap of the ball.

Ivy League sports history is littered with some incredible names and accomplishments, like Columbia’s Jim McMillian, who started for the Los Angeles Lakers during their amazing 33-game winning streak in the 1971-1972 season, the longest winning streak in major league U.S. pro sports history. McMillian averaged 18.8 points and 6.5 rebounds that year, for a team featuring Wilt Chamberlain, Gail Goodrich and Jerry West that won the NBA Championship.

In the 1930’s Columbia’s Ben Johnson, a track and field sprinter and contemporary of Jesse Owens, experienced a window where he was known as the world’s fastest man.

An eight-time NBA champion with the Boston Celtics, Tom “Satch” Sanders became the first African-American to serve as a head coach in any sport in the Ivy League when he took over the reins of Harvard’s basketball program in 1973.

Dr. George Grant, who graduated from Harvard’s Dental School in 1870, received the world’s first patent for his invention, the golf tee, in 1899.

Irvin “Bo” Roberson, Cornell class of 1958, is the only person ever to earn an Ivy League degree, an Olympic medal and a doctorate, along with having played in the NFL. Hall of Fame center Jim Otto once told the legendary journalist Dick Schaap that, “Bo was the Raiders first world-class athlete. He helped create the feeling that we were on our way to greatness. He pioneered the Raider tradition of great speed.”

In 1908, Penn’s John Baxter Taylor, who was a student in the Wharton School of Business, became the first African-American to claim an Olympic gold medal.

More recently, ESPN’s Doug Glanville and Marcellus Wiley had excellent careers in MLB and the NFL following their exploits at Penn and Columbia.

There are hundreds of other names and stories, unknown to the general populace, of extraordinary people who have come out of the Ivy League to make a tangible impact on society, both within and beyond athletics.

Beginning tomorrow, and every week thereafter during the month of February, we’ll bring you the stories of the four dynamic men currently roaming the sidelines at Cornell, Harvard, Yale and Penn. Their official titles might be “Basketball Coach”, but you’ll soon see, through their words, through their lives and through our storytelling, why they are so much more than that.

And don't be surprised, during this and future years' March Madness, to see an Ivy League team do what other schools from some non-traditional power conferences like George Mason, Butler, VCU and Wichita State have recently done and play their way into a Final Four while legitimately competing for a National Championship. Remember, don't let the smooth flavor fool you. There's a lot more to the Ivy League than meets the eye.

Harvard's Tommy Amaker, Part I