What bothers them? Her speed, or is it something else.

“Would it be easier for you if I wasn’t so fast?” Caster Semenya’s new Nike Ad

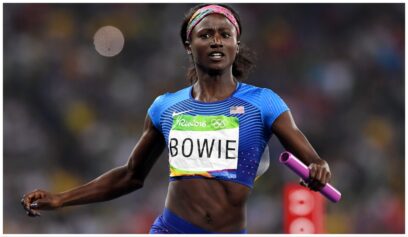

South Africa’s 800-meter World and Olympic champion Caster Semenya has a new Nike ad, which begins with the question, Would it be easier for you if I wasn’t so fast?

Semenya’s career is one that has been marred by controversy surrounding her success. In 2009, when she was just 18 years old, she won the 800 meters during the World Championships in Berlin, Germany in a time that was eight-seconds faster than her best time the year before. Such a leap in time raised many eyebrows, and caused people to speculate about her tremendous improvement.

The two most dominant theories surrounding her success were that either Semenya was doping or she was, in point of fact, not a woman but a man. As a result of the scrutiny that she received from fellow competitors and officials, she was subsequently subjected to sex-gender verification tests as a means of validating her right to compete as a woman.

Despite her self-identification as a woman as well as her parents, siblings, friends and national South African politicians (including president Jacob Zuma and Winnie Madikizela-Mandela) assertions of her self-identification, for most of 2010 Semenya was discouraged from competing pending the results of the International Association of Athletic Federation (IAAF) investigation.

Since the entrance of women into the realm of elite sports, their bodies have been subjected to scrutiny and testing. Though gender/sex verification wasn’t officially a part of elite sport until the 1968 Olympic Games, the bodies of female athletes were subjected to policing with respect to biological (genitalia) and social (femininity and beauty) characteristics and standards.

Over time, the testing of women’s bodies went from practices such as naked parades to contemporary practices of genetic testing. Such practices only serve to reify the existing gender binary, a binary that is fundamentally strengthened by colonial understandings of femininity and masculinity both of which are tied to the notion of race.

One of the dominant tropes of blackness is the conceptualization of the black athlete, and the characteristics that became associated with this trope frame representations of black women just as much (perhaps more) as they do for black men. The black athlete as a trope of blackness is coded as masculine, a centuries-old discourse that has heightened the belief that black women were mannish amazons.

That is to say, while black males as athletes get read as hyper-masculine, black female athletes are rendered not female at all. Though the inclusion of women into elite sport was marred by superior female athletes being labeled as mannish and masculine, for black women this becomes doubly coded in racialized and gendered tropes that have existed for centuries.

It is within this contested terrain that Semenya was subjected not only to sex/gender testing, but to commentary that sought to undermine her own self-definition.

In an article in the Associated Press in 2010, Semenya commented that she had been subjected to unwarranted and invasive scrutiny of the most intimate and private details of my being. Some of the occurrences leading up to and immediately following the Berlin World Championships (of 2009) have infringed on not only my rights as an athlete but also my fundamental and human rights including my rights to dignity and privacy.

This invasion of her privacy and infringement on her dignity was led in large part by her success on the track, and also by the perception that her self-presentation went against the feminine ideal.

One of her fellow competitors, Mariya Savinova of Russia made the comment, “Just look at her. These kinds of people should not run with us. For me she’s not a woman. She’s a man.”

Savinova’s statement was reified in the press as much of the media speculation about Semenya’s status as a woman focused on this like her physical appearance and style of running. Such emphasis begs the question of what it really means to be a woman in the first place.

Within the arena of sport, our understandings of race and gender, among other identities, are often reified along traditional and rigid boundary lines- male/female, black/white, masculine/feminine, etc. On the other hand, sport offers an opportunity to challenge the rigidity of traditional boundaries and broaden our understandings of race as well as gender.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6UW-VgxlIZI

In Caster Semenya’s new Nike Ad, you hear the stellar athlete in the background ask a series of questions, Would it be easier for your if I wasn’t so fast? Would it be simpler if I stopped winning? Would you be more comfortable if I was less proud? Would you prefer I hadn’t worked so hard? Or just didn’t run. Or chose a different sport. Or stopped at my first steps. That’s too bad, because I was born to do this.

Perhaps for some the answer to many of her questions would be yes, it would be easier, it would be simpler, and perhaps people would be more comfortable.

Perhaps Semenya would be more palatable if her success was dressed up in traditional gender stereotypical garb. If she wasn’t as fast, or as proud, perhaps the scrutiny and challenges she has faced would not have been as pronounced. But she is that fast, and she is that proud.

Her new Nike ad reminds us that there is more than one way to be a woman, to be a champion, and if we really want to challenge the racist/sexist system of sport we better take heed because she was born to do this.

***

Letisha Engracia Cardoso Brown PhD., is a Presidential Pathways Postdoctoral Teaching Fellow at Virginia Tech University. Her research focuses on representations of black female athletes as well as race, social relationships, and food practices. You can find her work in the South African Review of Sociology, and the Palgrave Handbook on Feminisms and Sport, Leisure, and Physical Education.