Florida A&M was picked to finish fifth in the Mid-Eastern Athletic Conference this season by the league’s sports information directors and coaches.

Aside from the high expectations of quarterback Damien Fleming and a handful of other FAMU players, no one’s really checking for the Rattlers on the HBCU football scene.

Defending MEAC champion Bethune-Cookman and South Carolina State should headline that conference. FAMU’s just a customer.

The reason football ticket sales saw a recent spike is connected to the return of the Marching 100 Band.

People seem to have put the uninhibited hazing culture (that led to drum major Robert Champion’s death in 2011) behind them, since the university is making anti-hazing strides in the community.

For the past 19 months, the band had been suspended from performing, practicing or meeting. Interest in football at FAMU proved to be indicative.

The university reported that ticket sales are up nearly double from a year ago. FAMU got scooped in the Atlanta Classic this year, after the 2012 game saw a significant attendance dip from its usual 50,000-plus.

The major takeaway from what happened to Champion and the Marching 100 is that hazing is best policed on a zero-tolerance scale.

Hopefully the lessons translate to the incoming classes of band members and athletes that hazing is intolerable, whichever end of it one finds themselves to be on.

A far more subtle note is how counterintuitive today’s historically black football programs are without a band. Peanut butter, no jelly? Ham, no burger?

In an interview with Tallahassee.com, FAMU head coach Earl Holmes explained that the band brings excitement back to the program and serves as a motivator for the football squad.

“That’s the whole thing about music. It just motivates the guys to push harder. It brings excitement back. I think everything will come together.”

Only at an HBCU can you come from a football game and not discuss a single play afterward, because the band performances get the critique that matters. And the Marching 100 isn’t just any HBCU band. It is the band. A main attraction.

Perhaps what comes with that social status in the community pervaded the organization, past disturbing, to flat out dangerous. An argument could be made that the band needs to continue learning its lesson from this, or maybe knocked down another peg instead of being reminded of how great it is.

Yet they are spectacular, and it does HBCUs no good to promote the best football team, but not the best band.

More seasons without the Marching 100 would have been a march to the end of a show with no encore. It would have, in effect, been the death penalty to a signature institution.

As FAMU administrators have discussed, the allure of the band is just as much a recruiting tool for prospects as motivation for the players who are already there.

The market saturation for “student-athletes” in Florida typically leaves FAMU on the outside looking in at the Gators, Seminoles, and Hurricanes of the state.

It is, however, an enticing landing destination for players looking to transition from FBS to FCS.

Former Michigan State wide receiver Juwan Caesar transferred to FAMU this summer to be closer to his hometown Miami. It was known in late May that Caesar would be leaving the Spartans program, but plans to attend FAMU didn’t surface until after the Marching 100 comeback announcement.

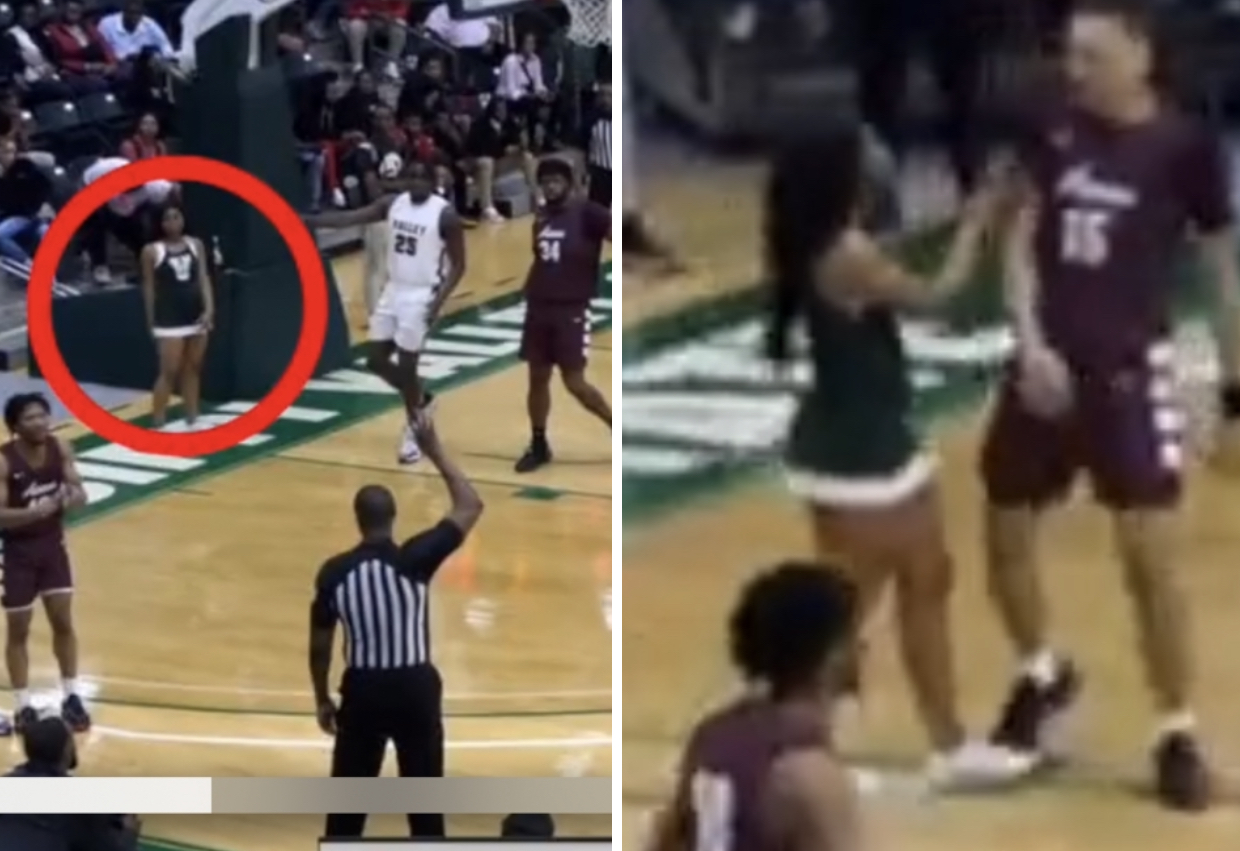

FAMU open its 2013 season on ESPN against Mississippi Valley State in the MEAC/SWAC Challenge presented by Disney, at the Florida Citrus Bowl in Orlando. On a global platform to start the season, FAMU is clearly looking to put its best foot forward.