The NCAA got fat while everyone starved on the streets.

The debate over college athletes being compensated, the one and done epidemic and transfer rules for athletes have long been debated, with the conversation intensifying over the last few years.

For the many thousands of student-athletes, the allure and benefits of playing college sports created opportunities that many would kill for. Looking in from the outside, many assume a full athletic scholarship and the opportunity to represent your school is reward enough for the tens of thousands of hours of practice, travel and sacrifice that athletes and their families put in to play in the NCAA. To some extent, that holds true.

But for athletes such as Ed O’Bannon, Morgan Harvey, Daisha Simmons, Jeremy Bloom, football players at Northwestern and many others who recognize the true value of what they create for their university, the NCAA has been a system of oppression similar to that of a plantation.

After pulling back the richly embroidered cloak emblazoned with NCAA royalty, these athletes recognized the disparity and hypocritical nature of the 501(c)3 organization that raked in $1 billion in revenues last year and are fighting for the rights of all of the student-athletes competing across all of the fields, arenas and stadiums across the country.

Another former student-athlete who is still speaking out against the NCAA’s current system is Olympic Gold Medal winner and basketball Hall of Famer Spencer Haywood, a man who is no stranger to this situation and was ostracized due to his criticism of, and fight against, an oppressive athletic system.

Full Court: The Spencer Haywood Story

On the heels of NBA legend Spencer Haywood’s recent induction into the NBA Hall of Fame, Seattle’s True Productions announces it’s currently in full production of Full Court: The Spencer Haywood Story, a riveting new documentary that examines the untold story of a man who changed the face of professional basketball forever.

In an interview with The Sporting News, Haywood discussed the situation which led up to his beef with the organization and how he unknowingly became the face of student-athlete activism.

After moving from Mississippi to Detroit to attend high school, Haywood was poised to attend the University of New Mexico. But after a summer of race riots in 1967 in the Motor City, Detroit’s Mayor Jerome Cavanagh and Michigan Governor George Romney approached Haywood and the man who brought him to Detroit, Will Robinson, with a unique proposition.

They would both stay in the city at the University of Detroit where Haywood would play for the team and Robinson would take over a year later as the school’s then coach, Bob Calihan, announced he would be retiring. This would give the reeling city of Detroit the Black “saviors” and leaders they needed to overcome the tumultuous year of 1967.

I wanted to do something good, Haywood said. For Will Robinson, for myself and for the city of Detroit, because I wanted to revitalize my city. My city had burned down. The city had taken me out of the cotton field and nurtured me to this greatness. People in the city were calling me, and I got a chance to do something for the city? It was like a no-brainer.

But as we all know, the business of politics is shady, so of course, this promise went unfulfilled after Calihan’s retirement. Instead of having a star Black player and the first Black coach in Division I history play in a city with a heavy Black population which sorely needed positive inspirations, the university hired a different coach and Robinson moved on to Illinois State, where he still became the first Black coach in D-1 history.

This left Spencer at the school with a coach he had no interest in playing for and he wanted out. But NCAA rules prohibited him from transferring, so he decided to take the pro route, and that’s when things escalated quickly and turned ugly for Haywood, who got his first taste of how shady contracts could be.

After signing a six-year, $2 million contract with the Denver Nuggets of the ABA, Haywood dominated to the tune of 30.0 points and 19.5 rebounds en route to taking home both the MVP and Rookie of the Year awards in the 1969-70 season. Yet the contract wasn’t what it appeared to be and the star player hired an attorney and took the team to court, which resulted in fan backlash and characterizations of an ungrateful athlete.

But what they failed to realize, and what was never mentioned, was that the contract was basically one akin to indentured servitude as the owner of the team, trucking line owner Donald Ringsby, created a contract for Haywood which basically mandated that he had to remain an employee of Ringsby Trucking for life to collect his $2 million.

Spencer Haywood’s Hall of Fame Highlights

Check out some of the best moments from the 2015 Basketball Hall of Fame Inductee, Spencer Haywood. About the NBA: The NBA is the premier professional basketball league in the United States and Canada.

What they didnt say about that deal is that it was a $2 million contract, but that contract was fraudulent, Haywood told The Sporting News, because what they were doing was putting the money in an annuity on Wall Street and I would be able to collect it from age 50 to age 70, and I had to be employed by Ringsby Truck Line. So, $1.5 million of this money, I had to live till age 70 and I had to stay employed by the truck line and the truck line did not exist later. So I would have lost that money, anyway.

The public refused to acknowledge his dilemma, instead feasting off a false narrative of an ungrateful athlete who should, for all intents and purposes, “just shut up and dribble.”

“At that time, everybody was angry at me, said Haywood. I am leaving Denver, and I am ungrateful because they gave me the chance to come in and play as an underclassman. But now I am going to challenge the contract and I am going to challenge the NBA and I am going to destroy the NCAA.

When word got out that Haywood might be on the market again, teams pounced and the recruiting process began. Haywood eventually settled on Seattle and another fight erupted which put him back in the line of fire as teams began to bad mouth him and poison both the union and current players against him.

So three years after the transformative year of 1968, a year which could be called one of the most pivotal and impactful years in Black American history, Haywood had to gear up for another fight that wasn’t of his doing, yet it was a role which he relished.

“You had John Carlos and Tommy Smith at the 1968 Olympics and Dr. Harry Edwards leading a movement of athlete activism.” Haywood told us in an exclusive two years ago. “I thought, ‘Well, maybe this is where I’m supposed to be.’ I threw myself into it and we filed suit against the NBA.”

“And they filed a suit and an injunction to not let me play. It went all the way to the Supreme Court, but in between there was so much drama.”

Most don’t realize how important Spencer Haywood is to today’s NBA, and how important his lawsuit, Haywood v. National Basketball Association, is to many players past, present and future. By challenging the NBA rules which stated that said a player was ineligible for the draft until four years after his high school graduation, or the graduation of his class in the case of a dropout, Haywood became a champion for the athlete and an enemy of the governing bodies such as the NBA and the NCAA.

Without Haywood’s resolve, the careers of players like Moses Malone, Kevin Garnett, Kobe Bryant and LeBron James might have been very different.

But Spencer, who grew up in Mississippi during the times of indentured servitude, recognized the similarities between the organizations and this covert form of slavery, which is why he refuses to remain silent in his feelings for the NCAA today.

They just got a contract from CBS (and TNT), $8.8 billion, and if you are making that, I think you have to share some revenue, stated Haywood. You cant expect people to continue to work for nothing on a false hope of, well this is about education, we are getting you an education, we will feed you. It sounds a little like 400 years ago, like slavery. Stay in your hut. Stay in that little house. Well give you some food. You do all of the work. All of it. And I am telling you that I will take care of you.

It sounds like my life in Mississippi. And I will just use myself as an example. We picked all of the cotton, from sunup to sundown. We did all of the work that had to be done on the farm, chopping cotton, planting cotton, tilling the soil all of this work. We were making so little money that we could not survive. We would go to the big boss and say, Hey can we borrow $50 so we can celebrate Christmas? The birth of our Lord and Savior. Then we had to pay that $50 back all year long. We were relegated to that same system, we couldnt leave, we couldnt leave that farm.

Same thing happens with the players. If they decide to leave, youre penalized. You transfer, you lose a year of eligibility. The coach decides to leave? He gets a raise.

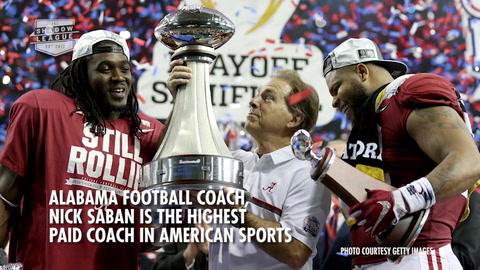

Nick Saban Gets Paid

When a commitment letter is signed, the benefits are outlined but the insecurity and indentured servitude-type relationship it omits is a pitfall which Haywood has been sounding the alarm about.

“Lets think about it. If you have 11 blacks on your team and you are say, in Kentucky, and theyre creating all this wealth but not getting paid? It does have a tinge of slavery.”

This is why Spencer Haywood’s life story is so important to understand, acknowledge and appreciate. He took on not one, but two Goliaths and beat them both, setting the table for current day athletes.

“I was 18, 19 years old when this was going on.” Haywood told us. “I went before the Supreme Court, not only fighting for my right to play, but many others who were coming behind me who would benefit.

“The great Supreme Court justice Thurgood Marshall pulled me aside and said, ‘Son, what you have done is monumental. You will never get your due in American history. But you made a stand for many people and did something that was right, like Curt Flood and Muhammad Ali.'”

With the constantly revolving coaching carousel, the long existing collegiate recruiting scandals, the exorbitant salaries that college coaches are commanding and the ridiculously large budgets of big time programs, it would pay for college athletes to learn about Haywood’s role in their fight for just treatment and thank him for his five-decade fight against the system of slavery that he deems to be the NCAA, a fight which didn’t benefit him as much as those who followed.

But being the man that he is, Haywood is content with his past as evidenced by his response when we asked him what he was most proud of.

“To see the wealth that I helped to create for African-American athletes. Before my case, that wealth was not accessible to us as players. My actions were the beginning steps in creating billions of dollars for the players that came after me. I didn’t financially benefit, but sometimes you have to step out on faith in order for others to benefit.”

And benefit is what today’s collegiate athletes are still fighting for.