The roar of the crowd was almost deafening.

“Ali! Ali! Ali!”

As the fighter made his way out of the dressing room, hopping to the beat of the music, with sweat dripping down his cheeks, he could hear the words of encouragement. He could also hear the irrational words, as he climbed through the ropes and into the ring, of the man sitting ringside who screamed, “You better win, Ali! I bet the rent money on you.”

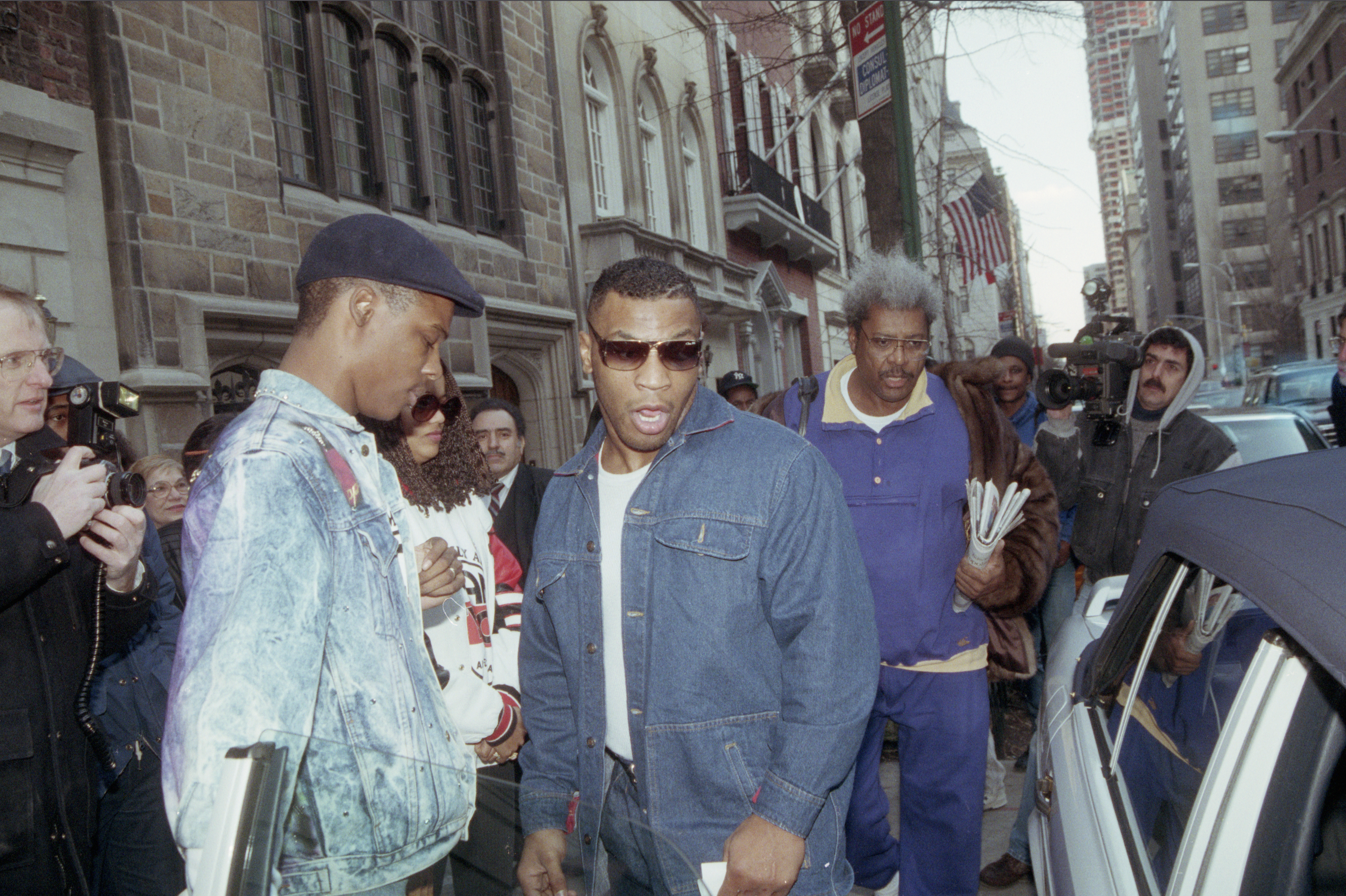

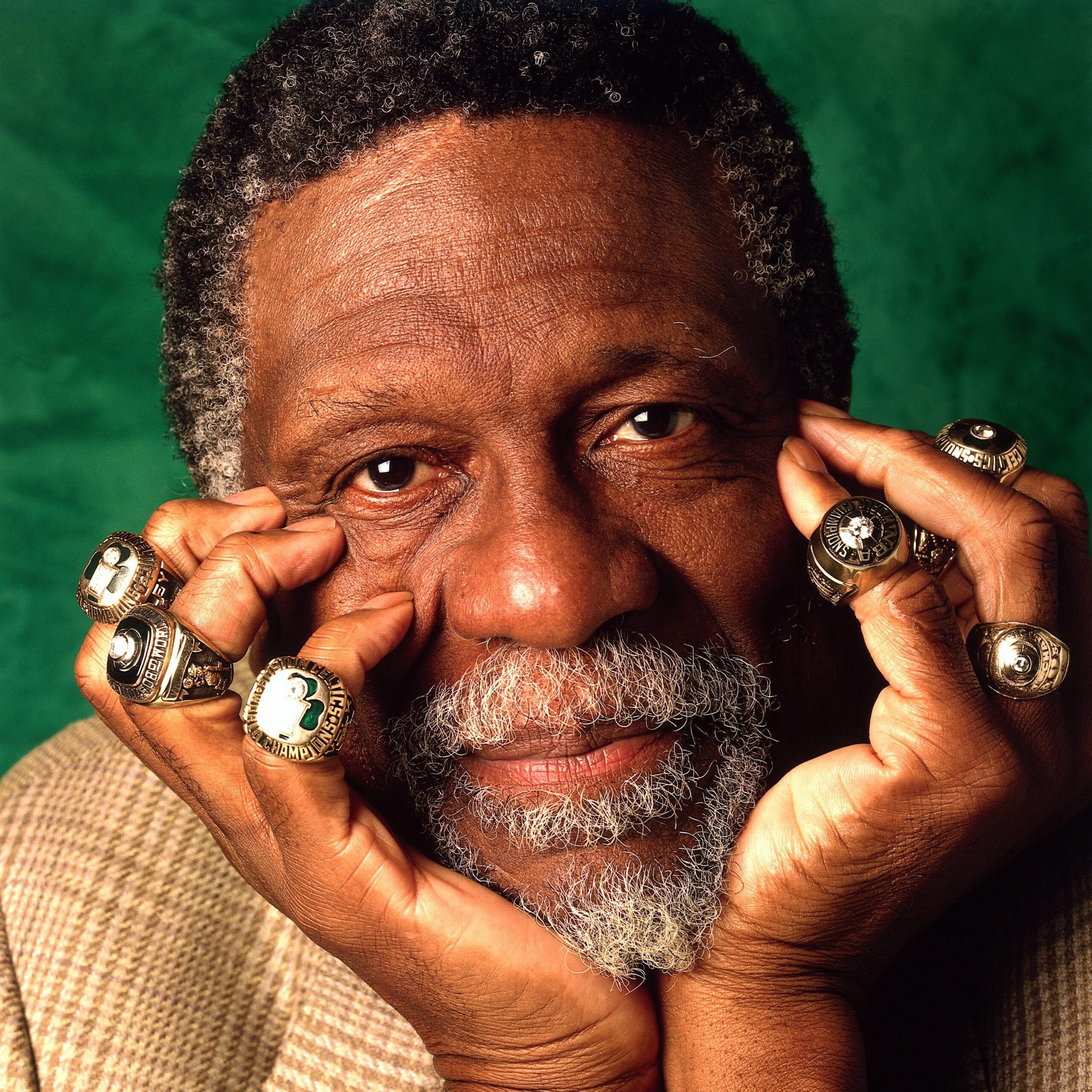

(Photo Credit: Getty Images)

That young boxer was me in 1982, at the Starrett City Community Center in the East New York section of Brooklyn, New York. I lived at the time in one of the largest federally subsidized developments in the country, which provided affordable housing for lower-income and working-class families.

I was 12 years old, the same age that Muhammad Ali was back in 1954 when, after having his bike stolen, he went to police officer Joe Martin’s boxing gym in his hometown of Louisville, Kentucky to learn how to fight so that he could whup the person who did it when he found them.

I was a member of the Starrett City Boxing Club at the time, a gym that was really nothing more than a large, musty room tucked away in the basement of a multi-story parking garage in the neighborhood’s “H Section.” It would later be one of the training grounds for future Brooklyn world champions like Zab Judah and Shannon Briggs.

My trainer would pack a bunch of us kids into his cramped car so we could watch NYC Golden Gloves legend, future Olympic Gold Medalist and World Welterweight Champion Mark Breland spar at the Bed-Stuy Boxing Association as well.

The thud of padded fists crashing into heavy bags, the ringing of the bell during sparring sessions, the grunts and groans of young boys and teenagers driven to push and prove themselves within the crucible of organized violence, the staccato wisp of jump ropes and the rhythmic resonance of the speed bag dancing along with coordinated hand clips was all music to my ears and soul.

Nobody had stolen my bike as an impetus for me to go there and train, but neighborhood disputes back then were settled within defined parameters. Sucker punching somebody meant you had no heart. That was frowned upon.

Respect was earned when, once it was apparent that a fight was about to go down, you stood across from a cat, knuckled up and went for yours.

We called it “Shootin’ a Fair One”: boxing bare-knuckled, toe-to-toe.

Getting good grades in school and rocking Clyde Frazier’s suede Puma’s or shell-toe adidas didn’t get you a rep in my neighborhood. Being able to handle the ball on the basketball court helped, as did getting your name in the local paper for scoring touchdowns in the local Pop Warner football league.

But you needed to have a knuckle game in order to get props from your peers and the older cats. That’s how we got down, bottom line!

***

Boxing was my first true love. And that was because of Muhammad Ali.

I began to form my sports consciousness at the age of four, right after his unanimous decision victory in the rematch with Smokin’ Joe Frazier. The sport was huge then, more popular in the black community at the time than the NFL or the NBA.

(Photo Credit: Getty Images)

My uncle Lino would play with me back then, not with my Hot Wheels or action figures, but by slap boxing and showing no mercy.

“I shook up the world! I’m the prettiest thing that ever lived!” he’d say over and over while tagging me mercilessly.

I took the phrase as my own, not learning until years later that it didn’t belong to Uncle Lino, but to Ali, who uttered it on February 25th, 1964 when, in one of the biggest upsets in the history of sports at the time, he defeated the ferocious Sonny Liston to become the Heavyweight Champion of the World at the tender age of 22.

The excited talk of him knocking out George Foreman and the Thrilla in Manila for his third fight against Joe Frazier captivated me. By the time I could watch and have a better understanding of Ali the boxer, he was on the decline. This was around the time he fought Ernie Shavers in 1977.

But thanks to one of my greatest discoveries – the majesty, beauty and power of books – I sat in the local library devouring everything I could get my hands on about Muhammad Ali.

And despite all of his accomplishments, from winning the Gold Medal in the 1960 Rome Olympics a mere six years after he began boxing, to beating Liston and up through the Rumble in the Jungle with Foreman and the dramatic trilogy with Frazier, I became more and more captivated by the composition of the man’s soul, rather than the sum of his phenomenal athletics gifts.

(Photo Credit: Getty Images)

Hearing how he’d discarded his Gold Medal due to the racist treatment he received upon returning home from the Olympics, and how he was stripped of his boxing license and passport for his refusal to be inducted into the army to fight in the Vietnam War, it all fascinated me.

He taught me, through his own personal example, of what being truly conscientious meant.

“I ain’t got nothing against them Vietcong,” he famously said. “My conscience won’t let me go shoot my brother, or some darker people, or some poor hungry people in the mud for big powerful America,” he said. “And shoot them for what? They never called me nigger, they never lynched me, they didn’t put no dogs on me, they didn’t rob me of my nationality, rape or kill my mother and father…. How can I shoot them poor people? Just take me to jail.”

The same power and agility that he showed in the ring was present in his thoughts and personality. My uncle Gary, a silver-tongued, politically astute street philosopher, would smile at my adoration of Ali. But he was quick to point out the sacrifices he made, how he criticized U.S. foreign policy and was ahead of the curve in illuminating the hypocrisy and fallacious nature of America’s role in the Vietnam conflict.

Uncle G told me the real lesson in Ali’s life was to stand up and fight for what was right, despite the consequences, how he wasn’t merely an athlete, but one of the most important figures within the Black American struggle and the turbulent Civil Rights movement.

He was so much more than just the greatest fighter to ever live.

Today, in lieu of his passing, this country celebrates him. He attained global icon status. But don’t ever forget how America treated him in the ’60s and ’70s. He was financially crippled, purposefully, by the government, and socially ostracized and vilified for raging against the machine.

To fully examine the depth of his sacrifice while forfeiting millions and the prime years at the crescendo of his athletic powers is awe-inspiring. I wish more of today’s athletes could understand and embody his essence as a man.

***

Back in 1982, when I sauntered into the ring with my hero’s bravado and exuberance for my amateur fight that night in the Starrett City Community Center, I quickly sobered up when my opponent hit me flush on the jaw. It felt like he was holding a brick in his boxing glove. I’d never been punched so hard in my life.

The man who said he’d bet the rent money was cursing me out, a grown man unleashing unspeakable profanities at a 12-year-old boy. I felt like telling him to step in there so he could get a taste of that ass-whipping that I was taking.

After foolishly standing toe-to-toe in round 1, I got my Muhammad Ali on in rounds 2 and 3. I danced, jabbed, shuffled my feet and hovered around the periphery of my opponent’s vicious hooks and uppercuts. I flicked a couple of punches, none of which landed with any substance, floated like a butterfly, stung like a mosquito, and was defeated rather handily.

(Photo Credit: Getty Images)

Slumped over when receiving the runner-up trophy, my trainer lifted my head up and said, “Smile. That boy has been fighting for years and he’s legit. He can punch his ass off. You’re just getting started. And I didn’t know that you could float like a butterfly. I’m proud of you. You showed a lot of heart. It might not get you far in boxing, but it will get you far in life.”

He gave me a fist bump after removing my mouthpiece, saying, “Rumble, young man. Rumble.”

“I shook up the world?” I sheepishly asked.

“Nope,” he laughed. “But you will one day.”

“I’m the prettiest thing that ever lived!” I yelled on my way back to the locker room, bounding past that idiot that lost his rent money.

Thanks Muhammad. You were the greatest.