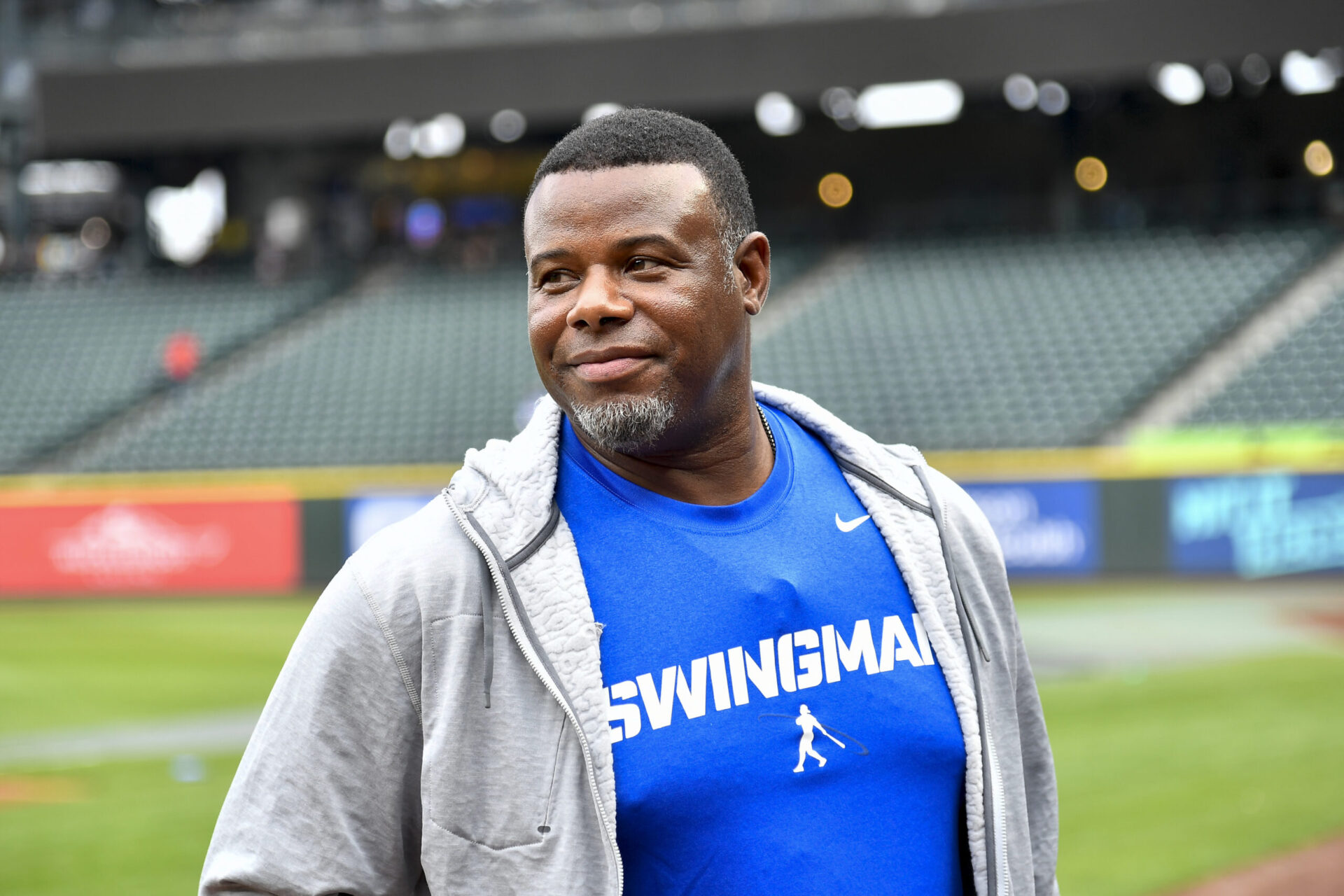

Ken Griffey Jr. and Mike Piazza traveled along two very different baseball paths, but ended up in the same place.The tale of these two dynamic ballplayers who were inducted into MLBs National Baseball Hall of Fame on Sunday is a classic example of the old adage: Its not how you start, its how you finish.

After entering the league with contrasting amounts of hype, both of these players became consistently explosive and clutch superstars. However, the main difference between these two guys in my eyes is the fact that Griffey Jr. has never been affiliated or associated with any performance enhancing drug use.

In fact, if “The Kid” did juice, he would probably have remained healthy enough to hit 800 homers and smash every record in the book. All of those games he missed, fighting injuries and the effects of crashing into old school walls with minimal padding and making incomparable fielding plays took its toll.

The effects of Piazza’s PED suspicions were reflected by BBWAA (Baseball Writers Association of America) voters who failed to give Piazza the necessary 75 percent of the vote in his first three shots at Cooperstown. There was even anecdotal evidence from people inside the sport, asserting knowledge of Piazzas PED use.

If the BBWAA is going to induct Piazza, they have to also induct Barry Bonds and Mark McGwire and Slammin’ Sammy Sosa and any other so called legend who didnt fail a PED test. I grew up in New York and dig the Mets, but Piazza cant get a pass because the media liked him a bit more than some other suspected cheats.

Does he deserve to be in the Hall of Fame? Yes, but to allow him to share the moment with Griffey Jr. is contradictory in nature and disrespectful to the Baseball God. Theres a funny taste in my mouth this morning. At the end of the day, however, Piazza’s induction should open the door for other suspected PED cheats.

Griffey Jr. was the son of a fine MLB ballplayer. His father Ken was a dope hitter and played outfield on some strong Cincinnati Reds squads. Junior grew up in the clubhouses, around the players, immersing himself in baseball. By his teenage years, he was touted as one of the next great ballplayers and his MLB commencement was highly anticipated.

Junior was the first pick of the 1987 amateur draft and became the highest pick ever inducted into Cooperstown. He was a sure-shot prospect who met every lofty expectation and still succeeded in shocking people with his exploits.

He was a human highlight film. The Dominique Wilkins of baseball.

Pops set the foundation and son took it viral. Griffey and his dad were the first MLB players to play on the same team together and hit behind each other in the lineup, even hitting back-to-back jax in a game.

Piazza, an unheralded 62nd-round pick – No. 1,390 – is the lowest pick to enter the Hall of Fame.

If not for his special relationship with former Dodgers skipper Tommy Lasorda, Piazzas baseball saga could have gone much differently. His career is also a classic example of the old adage: Its not always what you know, its who you know.

He was drafted by the Dodgers in 1988 as a favor from Lasorda to Piazza’s father, who was from the same Pennsylvania town. Initially a first baseman, Piazza switched to catcher in the minor leagues at Lasorda’s suggestion to improve his chances of working his way up the minor league ladder. It was a shrewd move.

Piazza made his major league debut in 1992 and the following year was named the National League Rookie of the Year.

He not only proved that he belonged in The Show, Piazza was an All-Star selection the first decade of his career. In 1996, he hit .336 with 36 home runs and 105 RBIs, finishing second in MVP voting behind Ken Caminiti. The following season was his best with the Dodgers. He hit .362, with 40 home runs, 124 RBI, an on-base percentage of .431 and a slugging percentage of .638, finishing second again, this time to Big Stick Larry Walker.

Piazza also played seven season with the Florida Marlins and then enhanced his legacy with the New York Mets. He was a part of some of the greatest moments in the Queens, New York franchise’s history. A rare player, who was able to embrace the pressure and spotlight of Big Apple baseball, he helped the Mets steal the back pages from the Yankees for a stretch.

The 12-time All-Star can reflect back on a career that leaves him at the top of the heap as far as career homers for catchers go and among the Top 5 most potent offensive catchers in history along with Roy Campanella, Johnny Bench and Yogi Berra.

Pitcher Al Leiter called him a rock star,” when he came to the Mets in 1998 and changed the culture, leading them to the World Series against the Yankees in 2000 and being an eloquent, sensitive but assertive leader when baseball galvanized to support New Yorkers and bring relief to an ailing city following the 9/11 terrorist assaults. Piazza’s game-winning blast at Shea Stadium after 9/11, in front of a crowd of policeman and fireman and families of those lost, forever, immortalized him.

(Photo Credit: metal.or.jp)

If not for the lingering PED suspicion, Sunday would have been a perfect moment for Piazza, the last of a dead breed of power-packing catchers who hit middle of the order.

Griffey played 22 MLB seasons with the Mariners, Reds and White Sox and was selected on a record 99.32 percent of ballots cast. Griffey was a baseball culture unto himself. He had swag for days, wore his hat backwards, flashed a million dollar smile with a $10 million swing of beauty. He could do everything on a baseball field and he did it so much better than anyone else. He was so special that people had the misconception that it was easy for Griffey, AKA The Natural, to accomplish his feats.

“There are two misconceptions about me — I didn’t work hard and everything I did I made look easy,” Griffey said during his acceptance speech. “Just because I made it look easy doesn’t mean that it was. You don’t become a Hall of Famer by not working, but working day in and day out.”

The effect his presence had on the baseball community was profound. Hes the last African-American baseball icon and with his retirement came a slow deterioration of black baseball culture and interest.

A 13-time All-Star and 10-time Gold Glove Award winner in center field, Griffey hit 630 home runs, sixth all-time, and drove in 1,836 runs. He also was the American League MVP in 1997, drove in at least 100 runs in eight seasons, and won seven Silver Slugger Awards. Major Kobe Bryant type stat-stuffing.

Griffey, who fell just three votes shy of being the first unanimous selection, hit 417 of those homers and swiped 10 of his Gold Gloves with the Seattle Mariners, where he played his first 11 seasons and took them to the playoffs for the first two times in franchise history.

“Thirteen years with the Seattle Mariners, from the day I got drafted, Seattle, Washington, has been a big part of my life,” Junior said, as he capped his career with his signature hat to the back. “I’m going to leave you with one thing. In 22 years I learned that one team will treat you the best, and that’s your first team. I’m damn proud to be a Seattle Mariner.”

He also shouted out African-American MLB superstars such as Rickey Henderson, Ozzie Smith, Dave Winfield, Eddie Murray, Alvin Reynolds, Kirby Puckett and Barry Larkin. These guys were part of a baseball brotherhood that birthed Griffey’s generation of Black diamond minors and had a supreme influence on him throughout his career.

Two men, beginning at opposite ends of the spectrum met on Sunday at the apex of their professional careers in Cooperstown, the last stop for baseball immortals. In a perfect world, I could give Piazza his proper due for his incomparable rise from zero to hero in baseball. As soon as the other greats, who have lived no differently than him, are given their just due. Anything other than that sullies the Hall of Fame more than any PED user ever could.