“Broken glass, everywhere” remains one of the most recognized lines in Hip Hop history.

Hip-Hop has always maintained a strong connection with both the streets and the social issues plaguing the urban communities which give birth to the the genre’s stars.

Over the last three decades, we have been gifted with lyrical descriptions of the struggles faced within our inner city landscapes across the country. From Chuck D addressing the drug epidemic in “Night of the Living Base Heads” to N.W.A. explicitly expressing their anger towards the police in “F* tha Police“, Hip-Hop has always flowed with the pulse of the city streets. The beats might be pulsating and the lyrics vicious, but it is the passion, poetry, metaphors and messages that create meaning and long lasting significance, and it’s the latter ingredient that we literally honor thirty five years later.

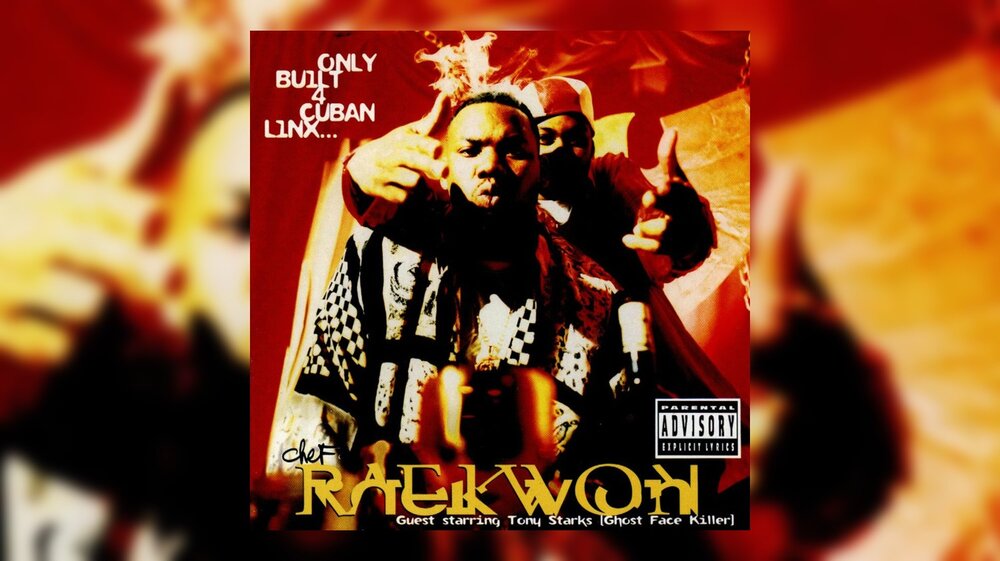

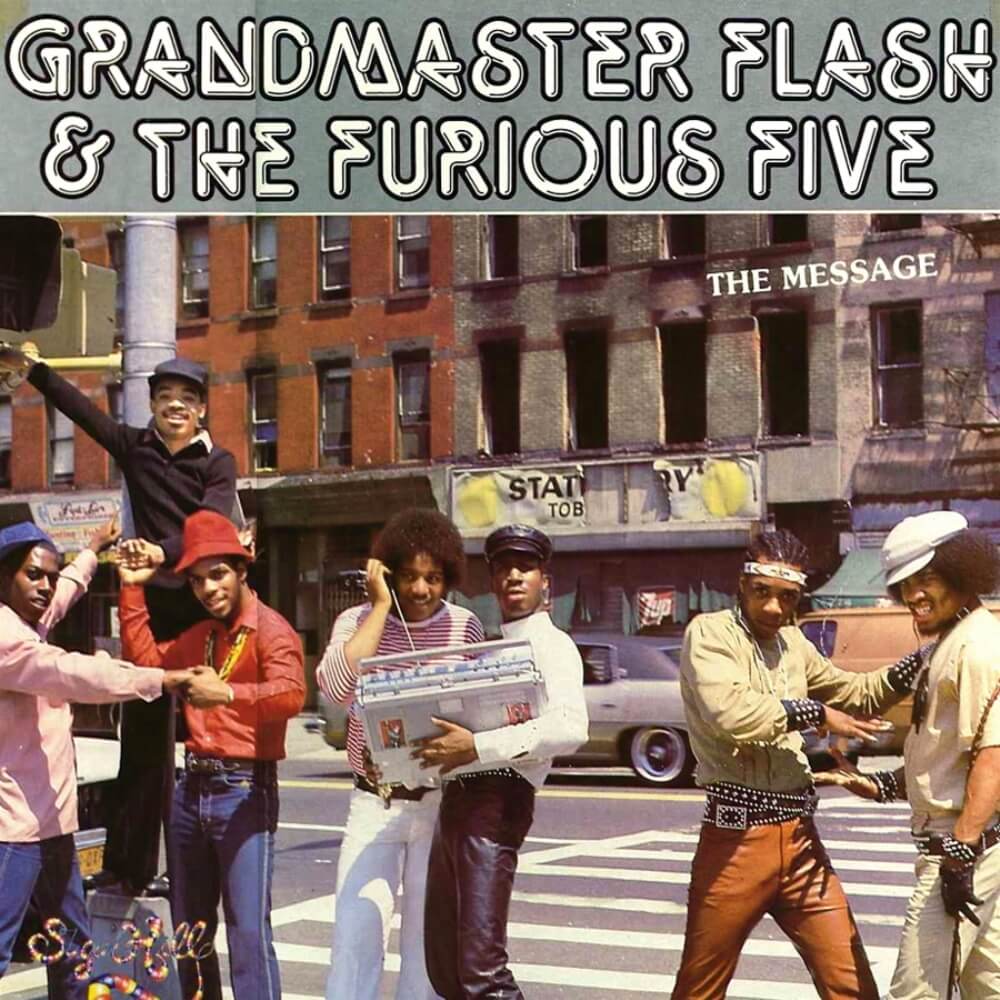

I was 11 when I heard Melle Mel exclaim, “Broken glass, everywhere!” and it was a phrase I repeated constantly while trying to maintain a gruff voice. It was July 1st, 1982 and Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five dropped their classic “The Message” on Sugar Hill Records, and it remains a record which has never lost its importance, significance or impact nearly four decades later.

WATCH: The Shadow League Video Tribute To “The Message”:

[jwplayer I6M6zfZh]

It’s a song which seems to waylay visions of current day New York, taking people back to a time that many have never experienced, especially the newer generation of city dwellers who weren’t exposed to the harsh realities of The City in the ’80s. Before Williamsburg and Park Slope were gentrified and Harlem became flooded with artificial, exploitative and conjured up titles like “NoHa”, there existed neighborhoods inhabited by working class people which suffered from urban decay, lack of resources and a general apathy from the powers that ran the city.

But none suffered more than The Bronx, a borough which became the poster child for urban blight and crime infested streets, and the setting for movies such as “Fort Apache, The Bronx” and forgettable bootleg movies such as “1990: The Bronx Warriors” and “Escape From The Bronx”, giving it a reputation for being plagued by crime, abandoned buildings, poor education and poverty.

While these issues did exist, residents couldn’t be blamed when city government diverted resources and money to other boroughs and pursuits, neglecting The BX and leaving it to fight against the reputation it had unfairly incurred.

Yet from this slight evolved a movement in The Bronx, one which birthed musical talents driven by the harsh realities of the streets who created a sound that eventually stormed its way across the city, country and world.

From the struggle came Hip-Hop, and one of the most notable names from that era was a group by the name of Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five.

Comprised of Grandmaster Flash, Melle Mel, The Kidd Creole, Keith Cowboy, Mr. Ness/Scorpio and Rahiem, they came together in the South Bronx in 1976 and conquered the party scene around the city. The group garnered street success, eventually signing with Sylvia Robinson’s Sugarhill Records, a label which achieved world wide success with the Sugarhill Gang’s “Rapper’s Delight” in 1979. A year later, the six new members of the label dropped “Freedom”, and the stage was set for success on wax for the crew from The Bronx.

From the second the needle hit the record and the call-and-response was posed to the crowd: “Somebody. If you want to party, say party!”, and once the response came, the party was in full effect.

But things weren’t always a party in the South Bronx, and the harsh realities of crumbling neighborhoods and rising rates in unemployment and crime could not be denied. So two years after releasing “Freedom”, the group, reluctantly, employed their newfound fame to shed light on social issues they faced everyday, and in 1982 they dropped the classic hit “The Message.”

Released a little over two months after Afrika Bambaataa & the Soulsonic Force dropped the classic “Planet Rock” on April 17th of that same year, the party vibe was relegated to the bench and a more conscious, harsher sounding song replaced it, one which audiences didn’t expect, but one that would take the party rocking group to new heights in their young music lives.

The stage for The Message’s purpose was enforced immediately with one simple verse: “It’s like a jungle, sometimes it makes me wonder, how I keep from going under.” Through that memorable opening poetic verse, urban life had officially been recorded on wax and a lesson about life in the ’80s ghetto was about to be taught.

It was a time that many in today’s gentrified neighborhoods can’t possibly fathom. But for those of us who grew up in the city, we can listen to the song and know exactly what they were illustrating through their rhymes.

It was a time when billboards for alcohol and cigarettes dominated building facades across inner city neighborhoods populated by Black and Latino families. When burned out buildings, destitute piles of bricks, broken furniture, abandoned cars and deserted blocks were common sights in the South Bronx. When extension cords were run from building windows and into street lights to “borrow” electricity. It was a period of graffiti bombed subway cars and stations that pre-dated Disney’s arrival in Times Square, when the area was inhabited instead by the flashing bulbs of adult theaters and peep shows.

It was a time when businesses like GEM Stores, V.I.M., Optimo Cigar, Twin Donut and mom and pop grocery stores were mainstays and lifelines for minority neighborhoods in the Five Boroughs. Before Target arrived, Alexander’s and then Caldor on Fordham Road were the places to shop.

(Photo credit: Forgotten NY)

Even the South Bronx-based Yankees were suffering through a losing season, their first since 1973, eventually finishing the year with a record of 79-83. To add insult to injury, Reggie Jackson, who was let go by the team the year before, returned to the stadium that April in a slump but crushed a home run off Ron Guidry to the delight of the fans who chanted his name.

Times were rough all around in the borough.

We had seen specific, and somewhat slanted glimpses, of urban life on the silver screen through Blaxploitation movies and films such as “The Warriors“, where gangs controlled the streets. But while these were classics to city dwellers, the majority of America was being exposed to sci-fi and horror films, shielding them from seeing what was really occurring just north east of the Big Apple.

But from hard times and hard lessons come hard words and hard truths, and that’s what “The Message” gave to us. They birthed descriptive verses of how crime was more influential for kids in the hood than hard work, school and other traditional images of success. How getting caught up in the streets and becoming a stick-up kid seemed appealing until you end up doing an eight-year bid. Yet when you’re surrounded by these elements, with no outlet or guiding force, you become a product of your environment, and unfortunately we lost too many to the life Melle Mel warned us about.

“You’ll admire, all the number book takers. Thugs, pimps and pushers and the big money makers.

Drive big cars, spending twenties and tens. And you want to grow up, to be just like them.”

This was a time decades before social media. Where information was shared through TV, newspapers and radio. Where 107.5 WBLS, founded in 1971, and 98.7 KISS FM, founded exactly a decade later, gave us the sounds and news most important to us. Where names like Joe Bragg, Bob Slade, Jeff Foxx, Wendy Williams and Yvonne Mobley dominated the urban radio waves and brought the community together through events, music, news and the legendary KISS Card.

(Photo credit: Kiss FM)

Where pioneers like Kool DJ Red Alert, Chuck Chillout and Mr. Magic fought for the right to put Hip-Hop on the air. Where, in 1983, “New York Hot Tracks” and Ralph McDaniel’s “Video Music Box” (channel 31, my old school New Yorkers) were the only places to watch urban music videos, way before MTV woke up and recognized the power of inner city America and the Hip Hop sound it had created.

(Photo credit: Nod Factor)

But in 1982, Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five gave us something extra special, a song which created a voice for those who weren’t being heard and who were ignored by a corrupt municipal government lead by Mayor Ed Koch and failing urban policies administered under Ronald Reagan. And through that single, the group dropped a bomb on the music industry and beyond.

“The Message” was more than just a Hip Hop song. It was more than just a lyrical lesson on inner city struggles. It has become a history lesson covering a New York from three decades ago, when it was a city that taught lessons the hard way, instilled common sense and gave its residents an edge which remained with us no matter where our lives took us.

“Broken glass, everywhere” and “Don’t push me, ’cause I’m close to the edge” were true representations of urban life, warning those around that we came from the gritty city and we weren’t afraid to “go there” if coerced.

It’s no coincidence that the video starts off by showing contrasting shots of Manhattan and the Bronx, quickly setting the tone for what was about to be discussed, and it was’t going to be sugarcoated.

Before Danny Glover made his formal complaint about taxi cabs not picking up Black passengers, this was just another reality persisting in a racially and socially divided New York. Not only did cabs blatantly bypass Black passengers, they also refused to take passengers uptown and to other boroughs, especially the Bronx. And that’s exactly what we saw as the video began, cabs dominating the streets in Manhattan the way bricks and vacant, decrepit buildings plagued the Bronx.

The recurring themes of poverty, drug addiction and the homeless were constant throughout the video, complemented by the profound refrain of “It’s like a jungle, sometimes it makes me wonder, how I keep from going under”, which further emphasized the seriousness of the subject matter, a fry cry from the group’s success in creating party music, which was something they hesitated in doing because of their success.

“Our group, like Flash and the Furious Five,” said Melle Mel in an interview with NPR, “we didn’t actually want to do “The Message” because we was used to doing party raps and boasting how good we are and all that.”

But sometimes the purpose is more important than what you feel comfortable in doing. And that purpose would go on to wield great influence decades later.

“The Message”, which peaked at #4 in the R&B chart and #62 in the pop chart in 1982, would be sampled by Ice Cube for the 1993 remix of “Check Yo Self” and by Diddy for his 1997 “Can’t Nobody Hold Me Down“, and it’s interesting to note that those two songs were also based upon titles of personal statements similar to Melle Mel letting everyone know about not pushing him.

It may be pure coincidence, but with the strong-minded and independent personalities of these two artists, one would have to assume that they incorporated the essence, and not just the music, of “The Message” into their hits.

And these types of statements are important parts of both the song and Hip-Hop. What started as party music was actually born out of the desperation, hunger and anger of the hood, so to continue include this element of telling people about themselves and providing warnings about who they were messing with was important to maintain years later.

The group’s leader, Grandmaster Flash (whose real name is Joseph Saddler), arrived in the South Bronx by way of Barbados. Through exposure to music at an early age and possessing an ability to create, Flash would give us classic songs and legendary DJ techniques such as scratching and the backspin technique.

Flash controlled the party scene, working with pioneering artists such as Kurtis Blow and Lovebug Starski, while also helping to create both party songs and more conscious-focused records such as “The Message” and another classic song reminding of issues plaguing our communities, “White Lines”.

Flash would go on to partner with Cowboy, Kid Creole and Melle Mel to form Grandmaster Flash & the 3 MCs before adding Rahiem (who left the Funky Four) and Scorpio to evolve into Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five.

Contrary to the negative perception The Bronx inherited, not everyone was hungry, poor or a criminal. Many were hardworking and trying to make it out, and through that pursuit originated the music which would challenge the world in so many ways. Through years of censorship, brutal honesty and unvarnished tales of reality, Hip Hop creatively forced the mainstream to adjust and accept it as an art form. And both the group and their music were instrumental in that struggle for acceptance.

“The Message” wasn’t rife with complex lyricism like songs from the ’90s, when Nas, Biggie and Jay-Z elevated the rapper’s skill requirements. Instead it illustrated through simplistic words and graphic descriptions of the environment. It wasn’t meant to start a party like “Freedom”, but it did start a special movement which focused on neglected communities.

They weren’t flexing their egos or bragging about material possessions. They were like a musical Eyewitness News group, detailing what was going on in New York; not a third world country but a borough less than 5 minutes away from Manhattan which seemed so foreign to those who feared to venture across the water.

And in certain areas of The Bronx, rightfully so.

Castle Hill, Tracey Towers, Fordham Road, the Concourse, the South Bronx. These were a few of the areas which people from outside would say with fear or a tone of condescension in their voices. They appeared dangerous, and in many cases, they were. But “The Message” didn’t shy away from these areas.

Instead they addressed the situation head on, showing these neighborhoods to strengthen their purpose, which was to let everyone know about the conditions in the borough. They wanted to generate awareness to help solve the issues at hand.

(Photo credit: The Village Voice)

The song arrived at the very beginning of the crack era, when heroin and alcohol had been the drugs of choice. The song could almost be viewed as a warning that something worse was coming and that if these issues weren’t addressed, bigger problems would arrive, which they did in the form of crack, which swept through the Bronx and other urban areas like a typhoon.

It’s like Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five were fortune tellers, predicting that everyday problems they witnessed were about to extend past the deserted areas they were once quarantined in, and the city was not ready, nor equipped, to deal with the crack epidemic and soaring unemployment rates of the Reagan era.

“The Message” was groundbreaking and trend setting, giving future artists something in which they could refer back to, whether it was for reinforcement of cause related to Hip-Hop, beat sampling or a point of reference, the group created a timeless masterpiece.

(Photo credit: Hip Hop Golden Age)

It was a work of art which would garner many accolades. Rolling Stone ranked “The Message” #51 in its 2004 list of the 500 Greatest Songs of All Time, which was the highest position for any 1980’s release and was the highest ranking Hip-Hop song on the list. In 2012, the publication named it as the greatest Hip-Hop song of all time.

In its first year of archival in 2002, it was one of 50 recordings chosen by the Library of Congress, and the first Hip-Hop recording ever, to be added to the National Recording Registry. And in 2007, Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five became the first Hip-Hop group to be inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

When WBLS and KISS FM merged in 2012 and ESPN was given the WRKS FM call letters, a celebrated artery of Black New York was ripped away. It represented more than just urban music. The station gave us a sense of togetherness by providing us with music, news and information which united inner city New York.

It gave us a place to listen to and discuss issues facing our communities across the city, and it gave us “The Message”, a song which DJs fought for the right to play, and a song which discussed how people fought to live.

If it wasn’t for Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five, and racially and socially divisive politics, we might never have been blessed with the lessons and enlightening lyrics of “The Message.”

And, as Lord Tariq and Peter Gunz once said, “if it wasn’t for The Bronx, this rap s*** probably never would be going on.”

There are numerous debates about the greatest Hip-Hop song, album and artist of all time. But there really is no debate when it comes to which one was the most important and influential.