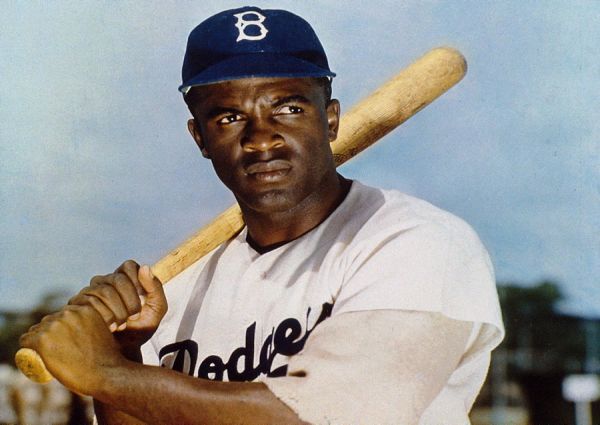

Photo Credit: Dodgers Facebook Page

We should pause for Major League Baseball tomorrow, April 15th.

In years gone by, it has always been the special day to celebrate Jackie Robinson, a man who changed baseball. Even more importantly, a man who changed this country forever.

Photo credit: LA Stage Times

This year marks the 70th anniversary of Robinson signing his first professional contract with the Brooklyn Dodgers organization in 1945, which was the first step towards his eventual breaking of the color barrier on April 15, 1947.

As usual, all players and on-field personnel will wear number “42” in honor of Robinson’s legacy to the game.

The twist this year is that MLB will also include the Civil Rights Game in the day’s celebration. The Seattle Mariners will play the Los Angeles Dodgers at Dodger Stadium.

It’s the ninth annual event, which honors the civil rights era in the United States and marked the unofficial end to the league’s spring training.

“I would like to extend my sincere appreciation to Major League Baseball for honoring Jack’s historic achievements and his fight for equality on and off the field,” said Rachel Robinson, the wife of Jackie Robinson, in a statement.

And while the NFL and NBA came to the inclusion party later, MLB has never forgotten African Americans and their impact on both the sport and society.

Black people need to both remember that and embrace baseball as well.

After all, baseball is OUR game too.

Somehow, we’ve lost our way, we think baseball is for others, not us.

We couldn’t be more wrong. Baseball is a part of our heritage and is cut from our cloth.

Since Robinson, it’s pretty amazing how dominant African Americans have been in a sport we weren’t even allowed to play in professionally until 60 years or so ago. The sport has been around more than twice as long.

When you look at the Top 10 players in homers all-time, black players hold four of the top six spots, including the top two with Barry Bonds and Hank Aaron, respectively. Babe Ruth is third.

And of the 26 players who have hit 500 or more, 11 of those players are African American.

Robinson’s impact was, of course, bigger than just on the field. He made black people feel proud, a part of an America which at that point treated us as second-class citizens with segregation.

That’s why blacks flocked to major league games to see him play with the Dodgers. Often times, they could only sit in bad bleacher seats, reserved for coloreds. And some racist owners even made our people pay double or triple the price for a ticket in an attempt to try to keep them out of the park.

And nonetheless, black people still showed up.

In the 80s, we started to stray. The Michael Jordan craze hit us and people wanted be like Mike. Makes sense. We happen to witness one of, if not the, greatest basketball player ever. People got caught on the game.

But remember, even Jordan wanted to play baseball. And he was willing to go to the minors to pursue it.

Sadly, the reason there aren’t as many brothers playing baseball today has a lot to do with two factors. No. 1, Major League Baseball outsourced many jobs 15-20 years ago. That’s when it started setting up baseball academies in Latin America.

It was a simple business decision. In the U.S., you’d often have to pay black and white players loot upfront and have to deal with agents and lawyers. That often wasn’t the case in the Latino community years ago.

Meanwhile, in our community, we had AAU basketball coaches making our kids quit baseball to focus only on basketball, some adding money to the pot as incentive to make the move to the hardwood.

No one is saying black kids shouldn’t want to play in the NBA or NFL. It’s just they shouldn’t shun baseball. They should play it as well and not be talked out of it by selfish coaches or stereotypical processes of thought.

Robinson — who was also a varsity athlete in football, basketball and track — changed this country forever, made us feel secure in being openly proud to be black in America for the first time.

We should never forget him or the idea that baseball is our sport, too. It always has been.

Photo credit: Lori Weintrob