It all started in March of 1945.

Wendell Smith, a young sports writer with the Pittsburgh Courier (the nation's largest African-American newspaper), called a Boston councilman, Mr. Isadore Muchnick, who was campaigning for re-election in a predominantly black area. He suggested that to increase his popularity in the community, Muchnick should help arrange a tryout with the Boston Red Sox and the Boston Braves for several black players.

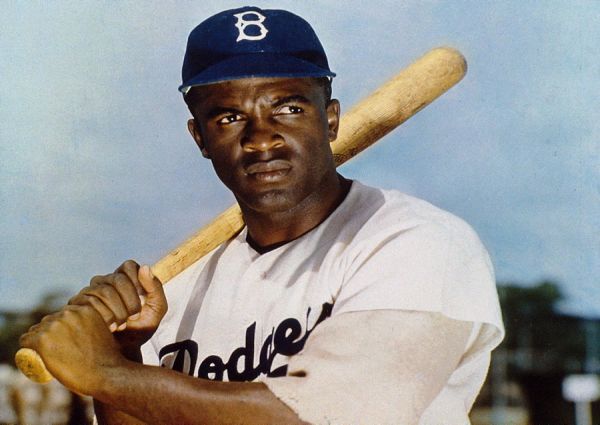

Muchnick agreed, and Smith chose three players: Marvin Williams, a second baseman for the Philadelphia Stars; Sam Jethroe, a speedy outfielder and .350 hitter for the Cleveland Buckeyes; and Jackie Robinson, a shortstop with the Kansas City Monarchs.

Smith knew that Robinson "wasn't the best player." However, Robinson had played on an integrated team and was among the greatest all-around athletes at UCLA where he had excelled in all the major sports.

Unfortunately, because of a scheduling conflict, the tryout with the Braves wasn't held. The Red Sox fulfilled their commitment, but the tryout was a farce. Young pitchers from their lower minor-league clubs threw to the black stars who rattled the left-field fence with line drives. It was not a real test. When it was over, Duffy Lewis, the Red Sox's traveling secretary who had been a star player many years before, told Smith, "They look like pretty good ballplayers. You'll hear from us."

A call did come but not from the Red Sox. It was from Branch Rickey, the general manager/president of the Brooklyn Dodgers. Rickey asked Smith to stop in at his Brooklyn office. Smith obliged and told Rickey what had happened in Boston.

"When I said, `Jackie Robinson,' " Smith recalled, "Mr. Rickey raised his eyebrows and he said, `Jackie Robinson! I knew he was an All-American football player and an All-American basketball player. But I didn't know he was a baseball player.' "

"He's quite a baseball player," Smith replied. "He's a shortstop."

Rickey called Smith a week later and advised he was sending Clyde Sukeforth, one of the Dodgers' scouts, to follow Robinson. Like others in the Brooklyn organization, Sukeforth assumed Rickey was interested in signing him for the Brown Dodgers, supposedly an anchor team in a third Negro league.

Smith knew better and asked Rickey, "Is there any chance of this ballplayer ever becoming part of the Brooklyn ballclub?"

When Rickey hedged, Smith realized history was in the making. He also understood there was no need to divulge these thoughts to Robinson. It would only add to the pressure.

Sukeforth followed Robinson for almost the entire season. Pleased with reports, Rickey signed Robinson to a contract with the Montreal Royals, the Dodgers' top farm club. At the same time he asked Smith if he would be Robinson's companion on the road. Rickey put him on the payroll for $50 a week, the same wage he was receiving from the Courier. Smith was listed on the official club directory as a scout.

Smith always considered himself as a member of the Brooklyn press corps and wrote daily dispatches for the Courier, chronicling not only the rejections encountered but the few welcome receptions. He also recommended several other stars from the Negro leagues, including Monte Irvin, Larry Doby and Roy Campanella.

Actor Andre Holland on Wendell Smith and 42 the movie: