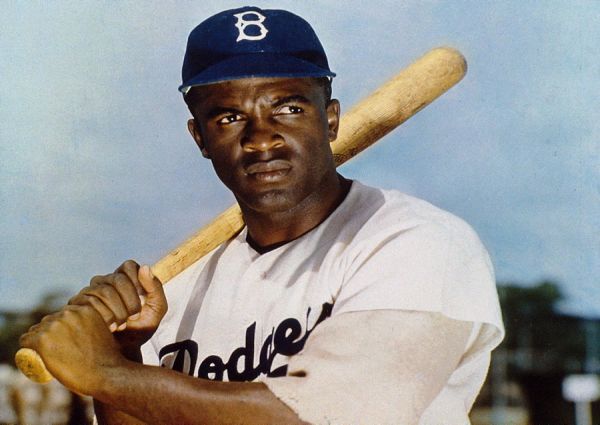

One year after Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier (April 20, 1948), Roy Campanella became the sixth black player to appear in the major leagues. He went on to become the second black player, after Robinson, to win the Most Valuable Player award, and eventually became the second black Hall of Famer, again following in Robinson’s footsteps. Campanella, however, holds the distinction of being the first black player to capture the MVP award twice and at the time of his death in June 1993, he was only black player to own three MVP trophies.

Campanella spent his entire career with the Dodgers, taking over as their regular catcher during the 1948 season and serving in that capacity through 1957, the franchise’s last season in Brooklyn. In those years the Dodgers won five National League pennants and a world championship. Prejudice and tragedy limited his major-league career to a mere ten seasons, the color of his skin delaying his debut until he was 26 years old, and an automobile accident prematurely ending his playing days at the age of 35.

Turned Rocky Relationship Came Full Circle

Robinson and Campanella became fast friends, rooming on the road, taking jobs together in the off-season and buying their first homes in the same neighborhood in Queens. Campanella’s son described his father as “the quintessential jock” who lived to play the game. Robinson, for his part, saw baseball as a means to larger ends. He pushed his reluctant black teammates to speak out against racism and to protest their exclusion from restaurants and hotels. Campy refused. “I’m a colored man,” he told a reporter. “A few years ago there were many more things I couldn’t do than I can today. I’m willing to wait.”

When Robinson retired after the 1956 season, the two men were barely speaking. Even Campanella’s car accident failed to end the feud. In 1963, Robinson invited black players to share their experiences for a book he was writing on civil rights and baseball. To his delight, Campy spoke passionately about what he had gone through and what needed to be done. “I am a Negro and I am part of this,” he said. “I feel it as deep as anyone, and so do my children.”

The two reconciled — one now in a wheelchair, the other ravaged by diabetes and heart disease. At Robinson’s funeral in 1972, Campy sat near the coffin, humming softly. He was at peace. The bond had been restored.

Click the video below to watch Part 1 of the Roy Campanella Story in "It's Good to Be Alive":