It only seems fitting as we celebrate the Martin Luther King holiday today that we also take a look back at the film Glory Road, which stars Derek Luke and Jon Voight, on the 10th anniversary of its release.

Based on the true story of the 1966 Texas Western squad that made history by starting five black players in the national championship game against Adolph Rupp’s all-white and heavily favored Kentucky Wildcats, it’s a story about the racism, ignorance and discrimination that was prevalent in athletics and the larger societal context at the time.

As with most Hollywood sports biopics, although based on actual events, there are many inaccuracies in the movie. Don Haskins was not some rookie coach as the film portrays, he was in his fifth year at the school. They weren’t some unheard of team that came out of nowhere, as Haskins had led them to two previous NCAA Tournaments.

Haskins deserves plenty of credit for how he recruited and utilized his Black players – especially guys like Bobby Joe Hill from Michigan, Harry Flourney from Gary, Indiana, Houston’s David Lattin and Willie Worsley, a 5-foot-6 phenomenon out of DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx, NY – but Texas Western had African-Americans on the roster before he even arrived on campus.

As a matter of fact, when Haskins was unloading the moving truck into his El Paso home after taking the job, one of the team’s players that he inherited, Nolan Richardson, who would go on to become a legendary national championship-winning coach at the University of Arkansas in the 1990’s, showed up to welcome and help him get situated.

The movie erroneously paints a picture of a team of new recruits that takes a while to gel during that 1966 season. In fact, the nucleus had been on campus for a while, winning 18 games the year before while qualifying for the NIT in 1965.

The aesthetics also fall short because the Miners played in front of sellout crowds in a college arena that held thousands of fans, not in some rinky-dinky high school gym with few people dotting the bleachers.

Technical and creative licensing issues aside, the movie is important because it exposes the story of the team that changed the face of college basketball to a wider audience, paying homage to an accomplishment that would radically alter the face of NCAA hoops.

Kentucky was a prohibitive favorite in the 1966 national championship game: think Sonny Liston versus Cassius Clay in Miami in 1964, Mike Tyson against Buster Douglass in Tokyo in 1990 and 40th Street Black versus Bootney Farnsworth in Let’s Do It Again.

The story fits into the celebratory Dr. King narrative because it’s really not about basketball, but the insidious disease of racism in society and sport. The college game was at the beginning steps of incorporating black faces on the court, but there was an informal rule that a coach never played more than one brother at home, two on the road or three if you were behind.

Don Haskins and that Texas Western (now known as the University of Texas at El Paso, aka UTEP) urinated upon those unwritten rules.

(Photo Credit: utepathletics.com)

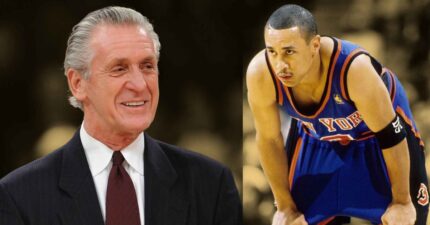

Hall of Fame coach Pat Riley, the current President of the Miami Heat who was at the helm of the Los Angeles Lakers Showtime dynasty of the 1980’s, was a member of that 1966 Kentucky team who lost that historic national championship game to Texas Western, 72-65.

Riley refers to that game as basketball’s Emancipation Proclamation.

Glory Road doesn’t succeed so much as a film as it does in illuminating an under-reported chapter in history, a moment when an invisible barrier got tossed aside. It was a pivot-point in the further recruitment and expanding scholarship opportunities for African-American athletes in the south.

The movie also gave a history lesson to many who were uninformed, becoming the accelerant that expedited the team’s 2007 induction into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame.

The Texas Western Miners didn’t simply win a national championship, they also gave us a glimpse of what was coming in the future.