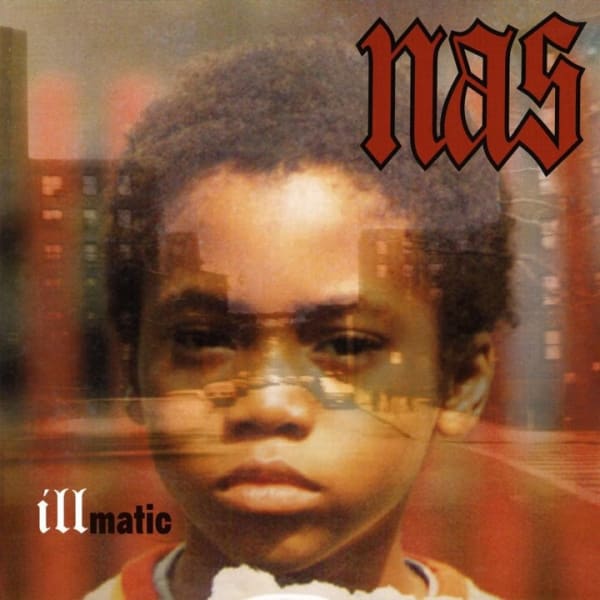

April of 1994 equaled 30 days, from start to finish, of emotional highs and lows for those of African descent. The fourth month of that year saw the start of hundreds of thousands of Tutsi massacred in Rwandan genocide. On April 29th, South Africa held its first interracial election where the late Nelson Mandela was voted president. And during all of this, on the 19th day of a month known for bringing showers, Nasir Bin Olu Dara Jones sprinkled the world with intelligent spit by dropping the five mic masterpiece Illmatic.

His unforgettable debut was hip hop’s gritty version of The New York Times. Filled with clearly colored commentary on life in the hood, Nas was an unapologetic, master weaver of mental visions illuminated on pieces of paper. Effortlessly, he sewed together the “ills” and black epidemics of generational incarceration rates, project crack whores pining for more, and fatherless boys fast-tracked into becoming emotionally numb men.

That social progression evolved into now, twenty years later, as one of the greatest MCs of all time celebrates the release of rap’s pivotal classic with llmatic XX. A double anniversary album, it's filled with reminiscent original singles and remixes to longtime hits of the past and rare tracks that crackle and pop to specks of dust beneath turntable needles. This two decade tribute to Nas’ introduction to the world is coupled with the global premiere of the documentary Time is Illmatic.

Directed by One9 and written by Erik Parker, Time is Illmatic kicked off this week’s beginning of the Robert De Niro and Jane Rosenthal founded Tribeca Film Festival. Its historic, opening night debut, took place three days prior to the exact date when llmatic was released on April 19, 1994. The irony of this perfection, being the timing of Tribeca coinciding with the original drop date of Illmatic, shows that in some great spiritual book of what’s meant to be, this monumental moment was definitely written.

The film begins before Nas is born. It highlights the roots of his father, jazz musician Olu Dara, in Natchez, Miss. A Southern man with Northern Negro tendencies, he was accustomed to Ku Klux Klan occurrences and colored water fountain sightings. Working the chitlin circuit as a struggling jazz artist, Olu fell for postal worker Fannie Ann Jones and moved with his lady love to New York City. They eventually found themselves living in the clustered, crowded projects of Queensbridge, NY.

Their two-parent home allowed for shared resources and inner-city luxuries of the ‘70s and early '80s, like color TV and a fully decorated living room of furniture. But Nas, a bright and aware voracious reader of his parent’s library of historical and biblical books, slowly became conscious and saw that his blessed lifestyle was not the neighborhood norm.

As the rarely shared moments of Time is Illmatic continue, Nas’ childhood personal world is dissected and forever changed by the defining moment of his parent's breakup and father’s exit. Now part of a single-parent dysfunctional household, Nas and his brother Jabari became African American statistics. Misunderstood and ignored by teachers, Nas was placed in “special ed” classes that helped push a bored kid to drop out before reaching high school. It was a controversial decision that was supported, much to the disapproval of the Jones family, by dad Olu Dara. “I didn’t want them to be suppressed and beat down by the system,” he explains in some of the saddest scenes of Time is Illmatic. "Enrolling them into school was like enrolling them into Hell."

Free from having to attend class, Nas and his brother were babysat by the streets. Jabari a.k.a "Jungle," who gives much of the films' commentary decked out throughout in bright, blood red colors, seems to have comfortably embraced his life in the ghetto. While Nas, who also played on corners, was drawn to the burgeoning hip hop scene of the 1980s. Loving his hood, but still wanting a way out, the beef between the teams of MC Shan and Marley Marl vs. The South Bronx anthems of KRS-One and Boogie Down Productions inspired his need to represent Queensbridge on the mic. A fateful meeting with rapper Roxanne Shante changed everything, after she stumbled upon Nas and his boys rapping in a project hallway and asked them to be her opening act.

Nas quickly created an "urban legend" reputation for being an intellectually witty, gritty, dark storyteller. Inspired by the disturbing visions of life, lyrics were like poetic journal entries. He wrote about friends locked up for 25 to life. And illustrated the toxic effects of crack smoke's contagious fumes. Like a hood griot, Nas effortlessly told tales of the Upstate fate of childhood classmates. And others killed as dealers making massive cash off tiny bags of rock.

It was his unique, harsh way of sharing that made him a favorite to work with among hip hop's veteran elite including Pete Rock, the Main Source, Q-Tip, MC Serch, and eventually Faith Newman, an A&R from Columbia Records who sought out Nas and eventually signed him to a deal.

Through excellent research, thought provoking questions, grainy Video Music Box footage, and beautiful photography, Time is Illmatic evokes a multitude of up and down emotions ranging from intense melancholy to proud happiness at the fact that hip hop and a black boy from the hood survived the times, beat the system, and made it this far.

Time is Illmatic took 10 years for One9 and Erik Parker to make. It took months for Nas to swallow his insecurities and deepest fears before finally agreeing to support and back the project. Thank God he did. Because this week, as he stood on stage at New York’s Beacon Theater, after his film was introduced by Robert De Niro to a room full of millionaires, rap legends, media veterans, Queensbridge thugs, fans, family, and loyalists – Time is Illmatic and its Tribeca debut poignantly shows the touching evolution of Nasir Jones. And that hip hop has finally, effectively, and intellectually, been recognized and televised.