Black baseball is on the rise and the centerfield position is key.

“There are no blacks in baseball.”

Baseball haters in the hood have to re-evaluate that stale and overused statement when discussing why basketball and football have become the sports of choice for African-Americans. We know baseball isn’t flooded with black players. For the past decade writers and baseball fans have offered endless theories as to what has caused the decline in black players on current MLB rosters. The presence of black pitchers and catchers, in particular, are as rare as an Ozzie Smith error.

But to say that brothers aren’t playing baseball is foolish and the MLB Network’s recent Top 10 Centerfielder’s list is the surprising proof. Analysts Brian Kenny and Darryl Hamilton broke down three Top 10 lists -which were all very similar give or take a few players – and black centerfielders dominated the list.

All of a sudden there’s this influx of fleet-footed brothers roaming centerfield. It’s almost as if we went to sleep and woke up with soul patrolling outfields all over baseball.

Center fielders Dexter Fowler (Colorado Rockies) Afro-Puertorock Coco Crisp (Oakland Athletics), Matt Kemp (LA Dodgers), Austin Jackson (Detroit Tigers), Andrew McCutchen (Pittsburgh Pirates), Adam Jones (Baltimore), Michael Bourne (Cleveland), Desmond Jennings (Tampa), Denard Span (Washington) and John Jay (St. Louis) all made the lists or were mentioned as just outside of that top tier.

With the exception of sky blasters Kemp, McCutchen, and Jones, none of these guys have tremendous power. Their games are based on speed, defense, getting on base and making things happen between the lines. Their overall style of play, are proving to be assets in this “new age” of clean baseball.

They all have intangibles— whether it be leadership, base-running savvy, grit or the clutch gene—that were often ignored in a homer-heavy Steroids/PED Era, which tarnished MLB and also nearly killed “black baseball.”

The PED-enhanced homer-fest created a reliance on the long ball. Baseball’s desperation to get the money machine rolling again and win back fans after the strike-shortened ‘94 season encouraged an atmosphere where steroids and other PEDs were rampant and eventually became part of baseball’s underground culture.

Consequently, the strategy of most managers shifted from the traditional aspects of baseball such as stealing bases, hit-and-runs, bunts and featuring speed as a game-wrecking weapon. MLB lineups began to resemble NFL football teams and the muscle-bulging, plodding, juiced up power hitter with these celestial slugging percentages became the player of choice. The stolen base – once baseball’s greatest weapon –became almost irrelevant as Earl Weaver ‘80s power ball became the blueprint for most MLB teams.

Weavers’ Baltimore Orioles didn’t play the small ball that a lot of managers indulged in. He was known for “waiting on the three-run homer” to change the course of the game. The basis of Weaver’s philosophy was; when you have a clique of power hitters throughout your lineup, there’s no need to risk losing base runners by stealing or attempting high-risk maneuvers. If you’ve got it like that, it’s much easier to sit back and wait for someone to hit a blast.

While the home run races of Sammy Sosa and Mark McGwire in 1998 and the generation of ballers who shattered offensive records returned baseball to its former glory and exponentially increased revenue, certain aspects of the game that were crucial to baseball’s historical appeal – particularly as they related to the black athlete – basically disappeared.

“All cultures bring something different to the game,” former New York Mets outfielder Gary Matthews Jr. said. “The African American player, there is a charisma that he brings from his culture … a little spice. That little spice is missing when we’re not participating.”

The black disconnect with baseball and the overall decrease in participation from the grassroots to the MLB level began about the time the Steroids Era was in full swing in the mid-‘90s.

By 2012, the African-American population in baseball plummeted to 8.05%, less than half the 17.25% in 1959 when the Boston Red Sox became the last team to integrate their roster, 12 years after Robinson broke baseball’s color barrier with the Crooklyn Dodgers. It’s a dramatic decline from 1995, when 19% of rosters were African-American. In fact, from 1990 to 1995, nine of the 12 American and National League MVP winners were African -American.

Then Adam ate the forbidden fruit and this time God looked the other way. Baseball was changed for the next 15 years, and its urban appeal waned as MLB’s marketing campaigns and appreciation for deftifying defense and daring aggression gave way to Pixie-Stix, 10-homer cats morphing into 30-homer Martians.

A trail of shattered-icons, drug-infested phenoms, Senate hearings and MLB commissioner-led witch hunts, broken hearts and busted dreams were left in its wake. Many of these sluggers made crazy amounts of money, but have since been exposed and are now dearly paying for their baseball sins as shamed ex-superstars who may never sniff the Hall of Fame.

It used to be commonplace for MLB teams to have a handful of African-American players on its rosters. At the start of last season, the San Francisco Giants had no black players. The Phillies had the most with five. The Red Sox, Diamondbacks, and Orioles each had one black basebrawler. According to data in Major League Baseball’s Player Diversity Report, released in November of 2013, big-league 40-man rosters were 62 percent Caucasian, 28 percent Hispanic, 8 percent African-American, and 1 percent Asian. It’s a stark difference from 1975 when 27 percent of rosters were African-American and the marquee ballers were largely brothers.

Even with some recent signs of baseball life in the African-American community, in 2012, Chicago Cubs center fielder Marlon Byrd was the lone African-American major leaguer in the city of Chicago and the only African American on the field at Busch Stadium in St. Louis during the 65th anniversary of Jackie Robinson breaking the color barrier.

“I don’t even know what to say,” Byrd told USA Today. “I remember when I came up with the (Philadelphia) Phillies in 2002, we had six (African-American) players. I thought that was the norm. Now, you look around and don’t see anyone. Will it change? I don’t know. I’m hoping it’s a different story four or five years from now.”

It’s understood we have a ways to go, but as early as 2010 we were seeing the positive effects of new testing and stricter penalties for PED users, as inflated offensive numbers began to settle into more reasonable rates of production. Baseball began to show signs of returning to “normal,” when on an April day in which all 30 teams played, 20 center fielders were African-American.

The group boasted All-Stars such as Torii Hunter, Vernon Wells and Curtis Granderson, but mostly it included some of the fastest rising young stars in the game at the time— 2013 NL MVP McCutchen, Kemp, Fowler, Cameron Maybin, Jones, B.J. Upton, Span, Jackson and Bourn.

Fast forward three years and all of these guys are still around and some are dominating the position. The diversity issue in baseball is becoming less and less about black participation. The numbers are what they are. Hispanics have a strong hold on the game and have replaced many of the African-Americans who once fancied baseball as a first athletic option. If Blacks could get their MLB representation back up to 10 percent, then that would be enough to justifiably say the black presence has returned to baseball.

The way the MLB Draft is trending, that double digit number may be attainable in a few years time. The first round of the 2012 draft featured seven African-American players, the most by total and percentage (7 of 31, 22.6 percent) since 1992. The MLB-sponsored RBI [Reviving Baseball in Inner Cities] program and the MLB Urban Youth Academies have seen hundreds of its participants get drafted and has introduced baseball to over 200,000 kids.

While these initiatives don’t guarantee black participation at the MLB level, black faces are still undoubtedly in the mix.

The athletic kid with his basketball tucked under his arm and his way to the courts, might stop and look at the TV for a minute if he catches a glimpse of Cincinnati Reds speedster Billy Hamilton—who stole a minor league record 155 bases last season—slide head first into third base after turning a walk into a triple.

Hamilton is a bolt of lightning in cleats and is expected to start in centerfield (Ken Griffey Jr.’s old stomping grounds) this season. He brings electricity to the game that baseball has lacked since Rickey Henderson was racking up triple-digit steals and giving pitchers ulcers and managers migraines.

The Reds are counting on the 23-year-old Hamilton to step into the leadoff hole left vacant by Shin-Soo Choo’s departure and bunt, swipe, swat and streak his way to glory.

Over his 19 big league at-bats as a September call up last season, Hamilton had a .368 average and .429 on-base percentage. He had a batting average for balls in play (BABIP) of .467, which included one bunt single. Most impressively, he swiped 13 of 14 bases like it’s nothing.

Straight game-wreckin’.

Best believe there will be a lot of black eyes on “Billy the Slid” this season. If marketed correctly he can single-handedly help spark the interest of the “black athlete” in playing baseball.

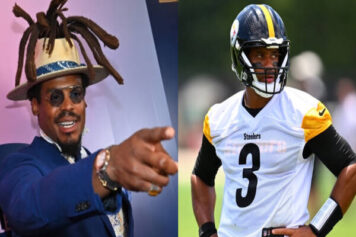

To put it bluntly, excitement is what brothers bring to the game, and baseball is a long way from becoming hockey or golf. Heisman winner Jameis Winston is playing college baseball at Florida State. Super Bowl winning QB Russell Wilson, who was also an MLB draft pick, joined the Texas Rangers in spring training and former NBA star Tracy McGrady is reportedly throwing in the low 90s and serious about revamping himself into a pro baseball player.

The black presence is once again being felt in MLB. It’s happening gradually and only a handful of these players can be considered superstars. Black baseball fans of this generation haven’t quite found their Ken Griffey Jr. yet, but cats are still eating. That’s even more of an indication that the black player “skill-set” is once again coveted and strategically and statistically in play in today’s MLB culture.