Nasty Nas was 17 years old when he showed up on Main Source’s “Live at the Barbeque.” He was 18 when he dropped “Halftime,” his first solo single.

Big Boi and Andre 3000 were 18 when their debut album Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik hit stores – a year younger when “Player’s Ball” hit the streets.

“Eric B. is President” came out when Rakim was 18.

Hip-hop has had its share of teen prodigies. In fact, Prodigy (and Havoc) of Mobb Deep released Juvenile Hell when they were teens.

Earl Sweatshirt, however, bests them all on the precocious scale.

I got hip to Odd Future a full year late. The first time they were mentioned on my crew’s Gmail music string was May of 2011. My boy Charles suggested we check the Radical album that OFWGKTA released as a crew. Three things stood out: 1) the teen-provocateur nature of the content (read: rape lyrics); 2) Tyler, the Creator’s production, which was like an update on and ode to ’90s-era RZA mixed with the Neptunes; and 3) this kid Earl, spitting like the child of Eminem, Pharoahe Monch and Kool G Rap. He was 16 years old. Sixteen!

From Radical, I worked backwards to Earl, which was a revelation. We can save the longwinded analysis of his music for his upcoming Doris. In advance of this album – what might be called, in archaic terms, his “proper” release – the ever elusive Earl allowed Fader magazine to corral him for a cover story.

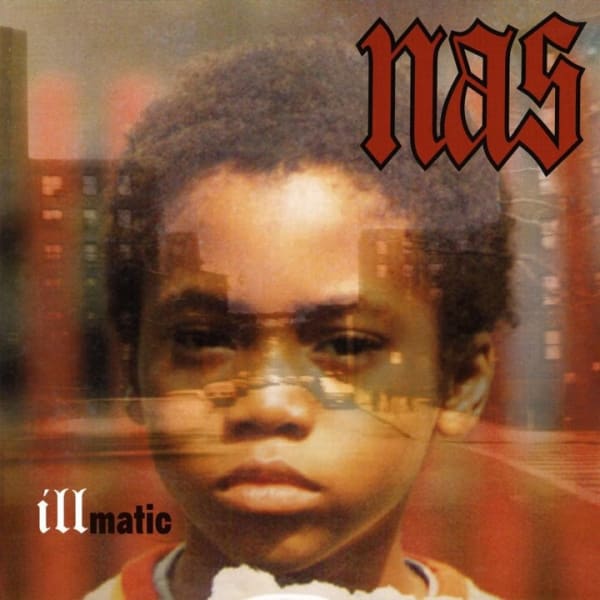

Perhaps the biggest takeaway from the well-done piece was how different the public climate is for young hip-hop artists, these days. Nas, Rakim and OutKast just didn’t have the same immediate interaction with fans and public sentiment back when fans/listeners’ only entrée to a burgeoning artist were radio DJs, mixtapes (ACTUAL mixed tapes) and The Source. Between “Live at the Barbeque,” “Halftime,” and “It Ain’t Hard to Tell,” most of the listening public had no idea what was going on with Nas. All we could do was wait-with-bated for Illmatic and keep our ears to the word-of-mouth rumor mill for nuggets here and there.

Earl’s situation was wholly different. On the precipice of fame following Earl, the kid’s mother sent him away to a school for troubled kids, to help him work through his problems. This upset the Internet.

Fader ’s Mary H.K. Choi details:

“Free Earl” became a rallying cry amongst Odd Future members and their rapidly multiplying followers. His absence would last two full years and it would later come to light that his mother, Cheryl Harris, a professor and lawyer, had shipped him off to reform school overseas. On April 14th 2011, Complex magazine discovered a student by the name of Thebe Neruda Kgositsile attending Coral Reef Academy, a military school in Polynesia. A month later, an eight-thousand word article in The New Yorker written by Kelefa Sanneh confirmed Earl’s whereabouts with official word from his mother and his estranged father, the South African poet laureate Keorapetse Kgositsile. Earl became a celebrity in absentia, a profoundly new phenomenon and a strange byproduct of Internet fame. There were “Fuck Earl’s Mom” chants at shows and even threats. In support of his mother and in defiance of every convention in rap, Earl asked to be left alone. “The only thing I need as of right now is space,” he said to The New Yorker in an email. “I’ve still got work to do and don’t need the additional stress of fearing for my family’s physical well-being. Space means no more ‘Free Earl.’”

That’s nuts on so many levels. Earl had to tell folks to, essentially, stop threatening his Moms. Throughout the Fader piece, you could sense how unsettling the whole experience was. Not just some of the displaced animosity that many of his fans (a lot of fellow teens) housed for his mother, but also the predatory music press, committed to invading the kid’s privacy. Doris’ lead single “Chum,” lets on to this:

The song is revealing, a fair vantage from which to lambaste those who intruded on his privacy two years ago: Craven and these Complex fuck niggas done track me down/ Just to be the guys that did it, like, I like attention/ Not the type where niggas tryna get a raise at my expense/ Supposed to be grateful, right, like, Thanks so much, you made my life harder and the ties between my mom and I are strained and tightened . He reinforces that he’s a real kid with a traumatized family, and not the prize to an elaborate scavenger hunt of the internet’s making.

Earl’s experience is yet another indication of the gift/curse nature of the Internet. On one hand, Earl, Kendrick Lamar’s Section.80 and Joey Bada$$’s 1999 were (virtually) self-released jumpstarts to promising careers. Their introductions to the public and aura development happened almost entirely apart from the music industry’s major-label machine. Nas, Rakim, EPMD, Q-Tip and a bunch of other prodigies from the previous era probably look at the new marketplace with a certain level of envy. But none of those cats had to worry about their mothers’ safety while they were in Polynesia trying to kick a drug habit. They had other personal challenges, for sure; just not of the Internet variety, the type that always seem to be trivial and grave all at the same disconcerting time.

When you think about it, “Free Earl” was probably one of the most contradictory Internet campaigns we’ve witnessed.