Everybody loves a kick-ass comeback story. That’s why NFL fans cheered every time Minnesota Vikings running back Adrian Peterson – who had embarked on a storybook season just eight months out from surgery to reconstruct the torn anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) in his right knee – broke for a big gain on the ground. That’s why everyone, outside of Minny, wanted him to break Eric Dickerson’s 28-year old rushing record. AP’s comeback was unprecedented.

It was almost as if AP’s knee had been reconstructed with robotic parts like he was ‘70’s cult classic TV character Steve Austin, The Six Million Dollar Man. No one had ever seen it done the way he just did it. He blew the doors off the so-called “two-year injury rule.” His feats of strength on the gridiron approached the damn near mythical. He became the baddest of the badasses. Peterson was proof positive that what doesn’t break you, makes you stronger.

“All or nothing, that was his mindset,” said James Cooper, trainer with Accelerated Bodies in Houston. “‘If I get hurt, I already know how it feels. I'll be fine. I can withstand the pain and I'll have to have surgery again, but I'm not gonna go out there and go half and be half of who I am and moving timid. I'm gonna be ready. You're gonna make sure I'm ready and I'm gonna make sure I'm ready.’ So that's the mindset that he had. No pity party. No excuses. No bullsh*t.

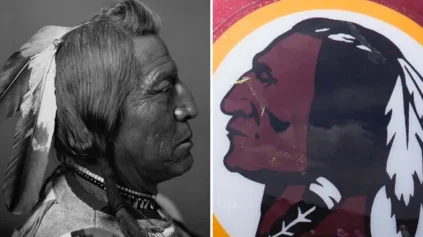

Now that Purple Jesus’ “can’t stop, won’t stop” comeback is fresh on everyone’s minds, all eyes are on Chicago Bulls’ Derrick Rose and Washington Redskins’ Robert Griffin III. Expectations are rising. Stakes is high. Pooh went down with an ACL tear in Game 1 of last year’s playoffs against Philly. RGIII suffered a similar fate on January 6th after his braced knee buckled while trying to scoop up a low snapped ball in the fourth quarter of the Wild Card game against the Seahawks. The most dynamic athletes to hit the ‘Go and Chocolate City, respectively, in a long damn time, felled by an injury that typically robs athletes of their speed, strength, agility and extraterrestrial athleticism like a stick-up kid.

The team physician who performed Rose’s ACL surgery, Dr. Brian Cole, surgeon of Midwest Orthopedics at Rush University Medical Center. was handcuffed on what he could say about the specifics of what when down in the operating room, but he did say in a statement that the surgery went really well and estimated that he’d need eight to 12 months for a full recovery. Renowned orthopedic surgeon Dr. James Andrews, founder of the Andrews Institute for Orthopedics & Sports Medicine, repaired the torn lateral collateral ligament in RGIII’s right knee and redid the reconstruction of the ACL that had been done in college, but he, too, was mum’s the word on what he did with scalpel in hand.“I can’t talk about a patient’s surgery,” Dr. Andrews said, citing HIPAA laws as it pertains to a patient’s medical privacy. “But he’s defied all odds. The better the athlete, the higher level of success rate you’ll have. A lower caliber athlete loses a half of a step, but somebody like Adrian Peterson, he’s a natural athlete.”

One can only assume that the good doctor told the District’s prized rookie QB the same thing post-op that he told Peterson after putting his knee back together like Humpty:

"Hey man, you're fixed. Go after it."

Pop quiz: Name some prominent athletes who went down with an ACL tear.

Stumped? Here’s a short list: Tom Brady, Adrian Peterson, Ricky Rubio, Jamal Crawford, David West, Frank Gore, Jerry Rice, Willis McGahee, Charles Woodson, Donovan McNabb, Wes Welker, Edgerrin James, Deuce McAllister, Mickey Mantle, Mariano Rivera and Tiger Woods.

Why the recap? To remind you that some of professional sports most renowned talents have stared down a torn ACL and successfully returned to their sport.

An ACL tear is usually the result of an athlete twisting his knee while keeping his foot planted on the ground, sudden deceleration or stopping while running full speed, suddenly shifting of weight from one leg to another, jumping and landing on an extended knee, stretching the knee beyond its limits or getting a direct hit to the knee, especially while its planted, like Peterson experienced while running in that fateful one-yard TD against the ‘Skins.

Back in the day, in the ‘60s and ‘70s, a knee with an ACL tear was called a “trick knee.” No, a trick knee is not a knee in Harry Houdini’s bag o’ tricks. It’s just an ACL tear that goes unrepaired. Players used to forgo surgery and keep playing which usually resulted in tearing their meniscus and developing severe arthritis over time. Not surprisingly, when they did repair an ACL, quack surgeons of the dark ages used synthetic material to replace the ligament, which drove failure rates through the roof. Surgeons also used to tear open a knee like a bag of chips, leaving huge scars. Additionally, they put casts on an athlete’s leg, immobilizing the knee for months, resulting in quads that looked like toothpicks from atrophy, making it mission impossible when it was time to rehab. This is why athletes like HOF tailback Gale Sayers and, more recently, former Falcon’s RB Jamal Anderson (1999) never made it back to the gridiron.

“Back then, we weren't really addressing the ACL,” said Dr. Richard Burke, orthopedic surgeon for Texas Orthopedic Hospital. “We were trying to do outside the knee joint to give the knee stability. But now, we’re actually trying to reconstruct the anatomy of the joint by putting that ligament back where it's supposed to be, by repairing the postal collateral ligament or using a tendon graft to actually get the knee to work as it’s supposed to.”

Nowadays, there’s a shift in surgeons using patella tendon grafts – which take six to eight weeks to grow into the bone – over hamstring tendons, which takes three months to grow into the bone. It takes about eight months for either of the grafts to become vascular. If the graft doesn't vascularize, it's still dead tissue. Another leap forward is surgeons finally 86’d the casts, allowing for quicker rehabilitation timelines and better return to sport rates.

“We're doing minimally invasive procedures now and we've been through all kinds of learning curves with different grafts and different techniques, since the early ‘70s and it's finally evolved,” said Dr. Andrews, who has also recommended stem cell treatment to heal an ACL. “Being able to do these arthroscopically has been the biggest invention for ACL reconstruction. We finally figured out that you couldn't just directly repair a torn ACL. The research showed that if you grafted an ACL, it would actually heal from the across the joint and actually become a living substance that had equal strength to the normal ACL.”

In the last two decades, the long-term prognosis and outlook for athletes returning to sports after ACL reconstruction has improved significantly. Now, the average time for return is six to nine months. That said, athletes still view the injury as a career setback. According to a recent study, most athletes don’t fully return to pre-surgery form until their second full season.

“None of us sports surgeons will make a claim that we can fix ACL and reconstruct an ACL as good as the good Lord made it,” said Dr. Andrews.

All Day was maniacal about his rehab. He was on it. Dig the skills on our boy. He came back less than a year after ACL and MCL reconstruction and rushed for 2,097 yards despite the fact that teams knew he’d be pounding in the rock on nearly every down. Dr. Andrews has given a lot of credit for AP’s comeback to physical therapist Russ Paine and Vikings trainer Eric Sugarman, but it’s James Cooper that really helped him push through an unprecedented quick recovery.

“Adrian’s goal was pretty much, ‘I wanna play, I wanna come back faster and stronger and have my best year. You tell me if that’s possible, you tell me what I need to do to make that possible,’” said Cooper, who has also worked with Redskins’ Trent Williams. “The first thing we did was create fluid range of motion, while at the same time doing a lot of balance training. We did a lot of deceleration work, not just positive explosion but negative explosion, too. We focused on simulating the environment he’d be put in on the field.”

RGIII just started his rehab. He has to hope his genetics allow his body to heal quickly if he wants to be ready to go when the season starts. Rehab and work ethic, rehab and work ethic. Repeat. But Derrick Rose, after storyboarding his comeback via Adidas ads, was just cleared for contact play. He’s on deck. It’s time to see what the kid’s got. For his part, Dr. Cole sees no reason why, statistically, D Rose shouldn’t be the same MVP-caliber player he was before the surgery with the proper focus on rehab.

“The priority is rehab,” said Dr. Cole. “What these athletes learn after they face this kind of adversity is how to put their heart into the rehab. They know that if they're going to return to the level that they were, or even better, they have to spend six to eight hours a day training in a way they may never have trained before (proprioceptive exercises). From the moment I’m in contact with an athlete, I prioritize and address their concerns and fears. They can indeed come back, but there’s work required. If they do the work, the payoff is there.”

While tremendous strides have been made in surgery and rehabilitation, the next important wave will come in the way of prevention.

“Every year, we see a faster, more powerful guy that can do things that people couldn't do and what goes along with that are certain movement patterns that puts them at risk,” said Dr. Cole. “Research now is looking at jumping and landing movements and patterns to identify potential risks for ACL tears.”

“Another way to prevent ACL tears is to focus on flexibility,” said Louis Ray, athletic trainer for Texas Orthopedic Hospital who has worked with Damon Stoudemire, Glen “Big Baby” Davis and TJ Ford. “By adding deceleration and range of motion training to their regimen, athletes can greatly reduce their risk for ACL tears.”

So if you’re an elite athlete and you tear your ACL on the field, the hardwood or the gridiron, get your mind right, because it’s not a death sentence anymore. You can beast your way back to the game if you don’t half-ass it. Thanks to medical science, and the advancements made in rehabilitation, you can come back bigger, stronger and faster if you have the right mindset.

All or nothing, baby. All or nothing.