The greatest mysteries in American history will all be revealed one day. Jimmy Hoffa’s body will be found. The murderers of Biggie and Pac will eventually be exposed. Baseball historians often contemplate why a player of Babe Ruth’s mythical caliber was passed over for managerial jobs he seemed like a perfect fit for.

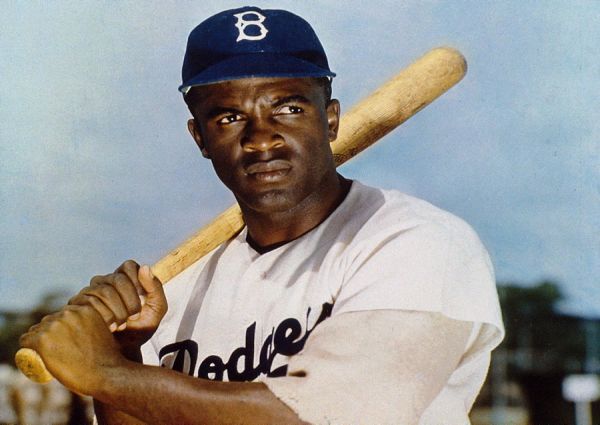

All these years later, like an unsealed FBI file, we are starting to get some clarity on that situation. In a refreshing feature for the New York Times, Peter Kerasotis catches up with Julia Ruth Stevens, the 97-year-old daughter of The Sultan of Swat. Stevens recalls stories of her father’s heroics and offers a jarring but totally understandable reason why the Great Bambino never fulfilled his desire to manage in the Majors. The greatest player ever was actually “blackballed” from managing, because of what Stevens says, was the fear that he would bring in black players, years before Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in 1947. "Daddy would have had blacks on his team," Stevens told Kerasotis. "Definitely.”

Ruth was known to frequent New York City’s Cotton Club and befriended black athletes and celebrities. He once brought Bill Robinson, a tap-dancer and actor known as Bojangles, into the Yankees’ clubhouse. Robinson also was with Ruth during the 1932 World Series in Chicago, and at the game when Ruth was said to have called his home run. When Ruth died in August 1948, Robinson was an honorary pallbearer.

Stevens also recalled her father speaking glowingly of Hall of Fame pitcher Satchel Paige, who wasn't allowed in the major leagues until he was 42. "Daddy thought Satchel Paige was great," she told the Times.

If Ruth and Satch were as chummy as Stevens implies, how different would history have been if old Satchel broke baseball’s color barrier. The hot-tempered, pitching legend with the 15-pitch arsenal might not have made it through one season in MLB in the late '30s-early '40s, and Juan Marichal may not have been the first noted minority player to take a bat to someone’s head in a game.

Even though MLB, Paige, and Ruth had to wait to see baseball integrated, Robinson, Branch Rickey’s union and their late 40’s entrance were perfectly timed. I guess it was how the baseball gods wanted it to shake out. It always struck me as odd that Ruth could never get a managerial job as much as he was revered. Movies depicting his life don’t even reveal the possibility that a threat of black ballplayers infiltrating the MLB in the midst of a volatile and segregated American landscape was the reason he never got to man the bench.

It all makes sense now. Ruth was a larger-than-life, iconic figure. In 1930, he signed a record $80,000 one-year contract, which made him the first baseball player to make more money than the President’s $75,000 annual payout. When a reporter brought this to Ruth’s attention he replied, "I know, but I had a better year than (President Herbert) Hoover."

He was his own man who called his own shots. On that Wiz Khalifa, “Work Hard, Play Hard” program, I can totally see him as a socially-hip and crazy cat jetting Uptown to hang out with the black celebrities and dabble in Harlem “taboos.” I can see The Babe getting along with straight-shooting Harlemites who obviously treated him as well or better than the white fans he partied with.

And Babe loved his ladies. So to think that he would deprive himself of the most diverse and beautiful race of women in the world doesn’t equate with who he was. Plus, he had a tremendous respect for Negro League ballplayers seeing them as equals—at least athletically. The reports vary on just how socially embracing Ruth actually was of blacks beyond fraternizing in the smoke-filled, liquor-heavy, sex-stenched clubs of the black underworld. But he didn’t have any qualms about getting it in with them socially. Babe was a wild boy and when he got paper, his life turned into an uninhibited, never-ending fiesta.

When Ruth turned 7 years old, his parents realized he needed a stricter environment and sent him to the St. Mary’s Industrial School for Boys, a school run by Catholic monks. St. Mary’s provided a strict and regimented environment. The religious influences of the Fathers at the school lessened any bigoted inklings within Babe. It also released him into the world free from the direction that once tempered his impulsive and temperamental nature.

Maybe his comfort and acceptance of blacks is what sparked rumors that Babe was actually of a mixed race . I always thought that his features – broad nose, full lips and olive complexion – kind of gave away the fact that he wasn’t of 100 percent European descent. Not to sound stereotypical, but the tales of his superior athleticism over the other Caucasian boys he grew up with, also makes me wonder.

The owners were probably scared to death to hire Ruth. If it was a known fact that he frequented black joints and hung in Harlem on the late nights, then as a manager, knowing how dope these Negro Leagues ballplayers were, Ruth might have started bringing his Uptown swingers into the sacred, white, baseball stadiums of America. But heads weren’t quite ready for that. Blacks were still getting lynched from the high-hovering branches of Southern trees and having their churches fire-bombed.

It was a risk too big to take and it led to the man that single-handedly made baseball America’s pastime, dying from illness and depression because he couldn’t match the thrill and fulfillment he attained as a younger player in his retirement years.

Ruth was the ultimate enigma and Catch-22. His revolutionary dominance as a baller, generosity, engaging personality, and need to be loved by people, were the catalysts for his lasting legacy.

His carousing, womanizing, rebel-rousing, and overall lack of maturity and discipline posed a problem for his managers. And while most execs probably agreed that seeing Babe on the bench would be a hit at the gates, he would ultimately have been a disaster as the head of a delicate, affluent organization in a position that requires discipline, maturity and reliability. Being a known alcoholic didn’t help his cause either, but he definitely made it easy with his progressive and liberal philosophies on race in baseball.

But a maturing Ruth wanted to manage. His daughter says by the time he retired and became serious about wanting to coach, he had already changed his ways, becoming a great father looking forward to the next chapter in his storied life.

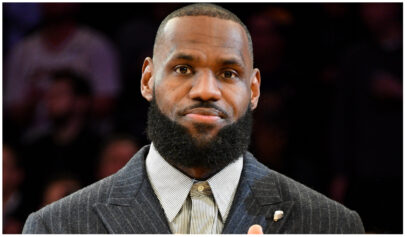

Maaaaan. They did The Babe dirty like he was Kareem Abdul-Jabbar.

Some think Kareem – a mythical NBA figure—can’t get a head coaching gig because of his past vocal opinions on race, his Muslim name, and the fact that NBA execs don’t want the head coach position to become a pulpit for opinions on race. And, you know, stirring up the brothers.

The Great Ty Cobb was a proud bigot and called Babe, “a nigger” many times on the field and said the rate at which Ruth blasted homers was destroying the game of baseball. Adultery? No problem. Drugs and alcohol abuse? They can get past that. But hanging with brothers and trying to bring them into MLB? No bueno. Back then, it was just a sign of the times.

Stevens’ comfort in exposing the truth about her father's post-MLB experiences is an example of baseball society coming full circle. Despite past criticisms, Ruth’s philosophies on integration show how much of a pioneer and trend-setter he truly was. Everything that was considered bad by white society, and which Babe supported, is now embraced and celebrated, in 2014, as the politically correct way of thinking. And I’m glad The Babe’s daughter finally brought it to light.