Jim Boeheim was no better a coach by the end of this season, even after squeezing all he could out of a one-year wonder of a freshman named Carmelo Anthony, MMonincluding Monday night's 81-78 defeat of Kansas in the Superdome for the NCAA title. He might, however, have been a different man. According to his wife, Juli, he had never never before told one of his players "I love you," as he did to Anthony, a 6'8" forward, after the Orangemen qualified for New Orleans with their East Regional

–Alexander Wolff, Sports Illustrated , April 14, 2003

>>

Kevin Durant, Greg Oden, Michael Beasley, Derrick Rose, Ovinton J’Anthony Mayo, Kevin Love, Anthony Davis, John Wall, Tyreke Evans.

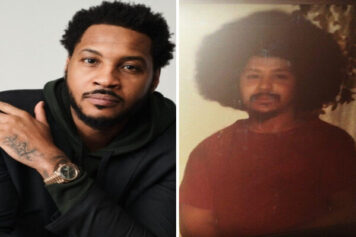

Pieces of their collegiate histories are traced to one Carmelo Anthony; it’s because of the current New York Knick that they all are viewed in the light that they presently exist in. The “one-and-done championship superstar” archetype was created by the B-more native. Never before had a freshman come aboard a program and led the charge to glory. It was unprecedented and unheard of. Undone. It changed everything.

Basketball programs all across the country searched wide and low for their shot at the next Carmelo Anthony.

And even when schools like Texas struck gold with players like KD, they (and others who have tried to find their own ’Melo) all failed to duplicate his championship-winning accomplishments and continue to fail today.

Sports Illustrated ’s Tim Layden depicted something somewhat inverse to Syracuse’s historic run more than a decade ago, during ’Melo’s lone season, from a coach that barely had any experience with the concept:

The one-and-done concept is worth evaluating. Calipari had guard DaJuan Wagner for one season at Memphis. (At week's end Wagner was averaging 20.3 points as a Cleveland Cavaliers rookie.) "If you have a guy who's going to stay one year and he's disruptive, it's not worth it," says Calipari. "DaJuan wasn't like that. We've got players who benefited from playing with him."

’Melo changed the game thoroughly, or as former Oklahoma Sooners coach Kelvin Sampson put it at one time, “He’s the LeBron James of college basketball, and he might be a better player.”

The legacy of ’Melo as a pre-professional is such that all freshmen are measured by his lone season with the Orangemen.

Maybe this is revisionist or just wistfulness, but that young freshman that led ’Cuse to the 2003 title played with such an exuberant, buoyant personality. He was a leader. He had charisma.

That has not been ’Melo’s rep as a pro.

He’s battled barbs that he was a malcontent, and accusations of coach-killing; and the big question has always centered on his ability to lead a team to true, “deep into the postseason/maybe a championship” success. Ten years ago, you just knew ’Melo was going to acquire some rings. He came into the league as a bona fide winner.

His rookie season seemed to maintain that trajectory. That year, he led Denver in scoring and helped the franchise end an eight-year playoff drought. ’Melo was at it again.

The same community forgot – abruptly – about ’Melo the Winner when the world thought he was playing, and acting, selfishly and petulantly for the ill-fated Larry Brown-led 2004 Olympic team. Then he was condemned a month later for being caught with less than an ounce of Mary Jane. A couple years later in December 2006, he was brawling with the Knicks as a Nugget (and subsequently apologizing for it) and appearing in “Stop Snitching” videos.

Through it all, Carmelo wasn’t exactly keeping pace with 2003 peers LeBron and Wade on the winning tip. By 2007, LeBron and Wade had both been to the Finals. ’Melo was good for a yearly first round exit. The Nuggets managed a deep run to the conference finals in 2009, which, coincidentally, featured ’Melo scoring at the lowest clip of his career, other than his first two seasons. That squad also featured Chauncey Billups, one of the great leaders and winners of his generation (Billups-led squads reached conference finals in six straight seasons).

Pushing his way out of Colorado to The Empire State – on the heels of LeBron’s scorned exodus from Cleveland – was the straw that broke the camel’s back.

“Any decision I make is the biggest decision of my life,” he said. “It’ll carry on and it’ll follow me for the rest of my life, too.”

It didn’t matter that it was reported that he “took exception to the idea” of desiring The Big Apple, or that his character was being questioned, or that he maybe didn’t give a damn about fans in Denver or that he wrote a note to the fans of the Nuggets about his love for them and his growth under their watch.

His abounding talent was misjudged for the bulk of his time in Colorado.

>>

April 2, 2013, for Carmelo Anthony, read like a how-to manual, a do-it-yourself guide, even. Never mind that the Miami Heat’s LeBron James and Dwyane Wade were absent from the game with injury, Anthony scored and matched his career high of 50 points in a game – all from beyond 15 feet and absolutely no layups (with another 40 earned on the next night against the Atlanta Hawks).

April 2, 2013, for Carmelo Anthony, read like a how-to manual, a do-it-yourself guide, even. Never mind that the Miami Heat’s LeBron James and Dwyane Wade were absent from the game with injury, Anthony scored and matched his career high of 50 points in a game – all from beyond 15 feet and absolutely no layups (with another 40 earned on the next night against the Atlanta Hawks).’Melo didn’t just cook; he made mincemeat of the Heat and even had some food left to give the dogs under the dinner table.

’Melo fans marveled. But, somehow, a 50-point game left plenty of room for critics to fire shots, pointing to his mere two rebounds and two assists.

The ’Melo we watch now isn’t the future ’Melo many of us envisioned as we watched him in that orange jersey 10 years ago. There was a do-it-all nature to his game at ’Cuse. He was a potent scorer, a double-double machine, and he often played point-forward. He was a revelation. Ten years later, he’s morphed into a man of narrow virtuosity. Gone is the board crashing, the playmaking – he's simply a scorer. He’s one of the greatest scorers we’ve ever witnessed, but still…that’s kind of like his only thing.

For years, ’Melo has received heavy criticism for this. He’s a good player, very good, but not transcendent, not excellent, not an NBA-savior like LeBron – or even D-Wade. The knock was that he didn’t work on his game enough, he was too selfish, and he was too rigid to be more than Bernard King 2.0. This started early in his career at Denver, and he’s yet to shed it.

Criticisms concerning ’Melo’s game aren’t so much about production – they’ve always been about how he produced. For the vast majority of his career, he’s been what some have called a “ball-stopper,” or more eloquently, an “isolationist.” When the ball came to him, he was going to shoot the rock, often far from the basket, usually in the far wing areas of the court. His raw production hasn’t changed much from Denver to New York.

Frankly, it appears that ’Melo’s problem has been his inability to break from the “high-volume scoring wing” mold to really become a threat closer to the basket, not unlike Dirk Nowitzki (who famously is known to have been an unlisted 7´1 small forward starting out at the three-point line before becoming a multi-position frontcourt threat).

Now that ’Melo has become the player the Knicks desperately needed, he’s, also, become a leader in the Most Valuable Player award race. He’s become all that the world had hoped that he might, and we all discovered something about him that hadn’t been readily apparent.

The evidence is clear that regardless of ’Melo’s hardheadedness in playing as a de facto power forward, he’s long been underutilized.

Based on the aforementioned data, it seems reasonable to say that he has turned things around, but what’s most telling is that the turnaround was based out of circumstance more so than self-reflection.

He fought playing in the post, and had Knicks coach Mike Woodson not made it mandatory, the Melo would've never seen the year that he and the Knicks are enjoying.

>>

The ’Melo of present is twice an Olympic gold medalist, an MVP candidate, a six-time All-Star, a principal ambassador for the Jordan Brand, and a probable Hall-of-Famer.

’Melo is finally starting to become beloved for the game he has played. Most of all, the adopted son of Baltimore and native son of Brooklyn can maybe hang his hat on an admission he made about entering the fire of the NBA, 10 years ago:

“I was able to step right in and live up to the expectations.”

But has he?

Think about this – what if Durant did nothing more than what he did in his second or third seasons? What If Durant hadn't worked on his fall-away jumper, or put the time in the weight room, or learned how to play more effectively near the basket? What if he remained the shell of himself he was as a Supersonic rookie, content with holding the ball and throwing threes up in the middle of the shot clock?

What if Durant hadn’t looked at himself, seen how he could be less selfish and not fall back solely on his shooting? He would be pre-2013 ’Melo – but this assumes accountability on ’Melo’s part.

It's not his talent that's the problem. He's an elite scorer, he's not undersized or slow — he's as quick as most wings and faster than the whole of his frontcourt competition.

When it comes down to it, the legacy of 'Melo is entirely up to him. He sulked when he's has undesirable talent around him. Even last year, 'Melo complained when New York adopted Jeremy Lin, and instead of supporting Lin, he blamed everyone else. The only way for the Knicks to be kings is for their leader to look at his face in a mirror and immediately forget what he sees in the reflection.